Women & children's / Quality improvement

Authoring for advocacy: experiences of writing a design brief on behalf of patients, families and staff at Great Ormond Street Hospital

By Stephanie Williamson and Louisa Desborough | 26 Aug 2016 | 1

This paper outlines a project to engage patients, families and staff at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust (GOSH) in the design of a new building. The project’s key objective was to ensure that the design aspirations of patients, families and staff were articulated at the outset rather than at a later stage within the constraints of pre-determined boundaries. The core approach involved creative dialogue inspired by user-centred design techniques.

Authors of scientific paper:

Abstract

Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust (GOSH) is halfway through an ambitious redevelopment programme to rebuild two-thirds of the hospital site over a 20-year period.

Phase 4 of the redevelopment programme will create a new building on Great Ormond Street. Occupying a significant part of the streetscape and incorporating a new front entrance, it will become the hospital’s ‘signature’ building – an architectural expression of a world-renowned brand. It will contain highly specialised inpatient and outpatient wards, diagnostic and treatment areas, facilities for patients and families, research areas, and clinical education space.

The project will involve a plethora of tough, complex design decisions and a meeting of many great minds – from leading healthcare design experts to clinicians and researchers working on some of the most significant scientific discoveries of our time. It will also involve supporting emerging models of care that will improve patient outcomes and enhance the patient experience.

The building must also support and nurture our patients and their families through some of the most challenging circumstances. The guiding principle at GOSH is “the child first and always” and our aspiration is to be the leading children’s hospital in the world. This new development must support this world-class aspiration with world-class buildings, which requires a rigorous brief to clearly articulate what our patients, families and staff need.

The emergence of design thinking and a growing weight of research evidence tell us that great design starts with great insight; a process that involves not merely intellectually understanding the problems that need solving but also making an emotional connection with them.

In developing this brief, we’ve employed the latest creative research techniques for engaging children and young people, in partnership with our professional in-hospital arts programme, Go Create! These included trials of Minecraft and 3D printing to engage patients in imagining their ideal hospital, as well as visualisation and use of metaphor in a technique inspired by the ZMET approach.

Our iterative process has vividly brought to life some of the problems our staff and patients face, and we’ve now started identifying creative solutions to these problems.

Keywords

Great Ormond Street Hospital opened in 1852 in a 17th century town house. With just ten beds at the time, it was the first hospital in the UK to offer dedicated care to children. The hospital’s principal founder, Dr Charles West, was a pioneer in that he recognised children needed dedicated and specialist care.

Early breakthroughs in treatment followed; specialist training for nurses was developed; and the tradition of designing medical devices for children began. Interestingly, the first ward was opened in the library of the house, which, on account of its highly decorated ceiling and panelling, must have created a magical environment for the children of London, most of whom would have arrived from the slums. From the start, Dr West had a vision for paediatric research and the importance of play was also recognised, with early pictures showing children playing with many toys on the floor and in their cots. Benefactors, including Charles Dickens, Lewis Carroll and Oscar Wilde, shared and supported his vision, leading to the hospital growing rapidly and beginning a process of redeveloping the site that continues to this day.

In 1987, the Wishing Well Appeal public fundraising campaign was launched, raising £54m for the development of the Variety Club Building, which opened in 1994. But it was the start of masterplanning at GOSH in the 1980s that paved the way for a further series of developments and major interventions around the site, culminating in the Mittal Children’s Medical Centre, which will be complete in 2017, and the Zayed Centre for Research into Rare Disease in Children, which will be finished in 2018.

Since its inception, Great Ormond Street Hospital has been at the forefront of specialist paediatric research and specialist care. This tradition continues today and it aspires to be the leading children’s hospital in the world for quality of care, patient experience and outcomes. Our guiding principle is ‘the child first and always’.

The hospital trust provides a mixture of specialised and highly specialised services for a local, regional and national population, and has a very active research programme. It does not carry out this work alone, working with a multitude of health and academic partners, including our principal academic partner University College London. It is supported by Great Ormond Hospital Children’s Charity, which provides a significant contribution for the trust, particularly in funding its ongoing redevelopment programme. These activities combine to create a globally recognised brand. Indeed, in the 2015 Charity Brand Index, the GOSH Charity was listed as tenth,1 and in 2016, it was awarded ‘Superbrand’ status.2

The next phase of development to commence – phase four – will be the largest scheme to date (as a single phase), and the most prominent, in that it will be an almost complete redevelopment of the buildings on Great Ormond Street itself. Along with the high brand recognition, this creates the opportunity for a signature project that will become the public face and architectural expression of this special organisation.

The importance of stakeholder engagement to redevelopment at GOSH

The following paradigms are often true of hospital redevelopment projects:

- briefing documents produced by the client side, albeit with the support of technical advisors, are often poor and focus on quantitative data such as functional content, schedules of accommodation, and compliance with technical guidance;

- interaction with end users is sometimes missing altogether, but even where it exists, it is frequently late in the project, superficial, bound by resource constraint, and severely time limited;

- designers working without a strong client vision and a clear statement of user need will design based on what they know and understand, and what has worked well on previous projects; and

- value engineering is undertaken by stakeholders far removed from the end user experience.

New developments must support our aspiration to be the leading children’s hospital in the world by providing a world-class built environment. A growing weight of research evidence tells us that great design starts with great insight, so early user engagement is central to achieving a quality outcome. The redevelopment team aspires to be innovative in solving design problems and has applied the principles of design thinking to the brief for phase four.

Design thinking is a creative and collaborative approach to solving design problems that seeks to put user needs at the centre of the process. It employs “divergent thinking as a way to ensure that many possible solutions are explored in the first instance, and then convergent thinking as a way to narrow these down to a final solution”.3

Rather than analysing a problem from a scientific perspective, design thinking frees up innovation by exploring a problem without the constraints of logic and assumed wisdom. It does not set parameters within which a problem should be analysed, or even start with the assumption that the problem is well understood. This iterative process is well suited to engaging a broad range of stakeholders at various stages of a project, and its focus on exploration and ‘blue-sky thinking’ is appropriate for an organisation that is dedicated to caring for children, and which has a well-developed understanding that ‘play’ is a serious and important business.

With its guiding principle ‘the child first and always’, GOSH has always been a strong champion of listening to patients and putting the patient first. Our approach is not to assume we know, but to put patients and families at the centre of decision-making. Rather than simply asking “what’s the matter with you?” we want to get better at asking “what matters to you?”

This commitment to patients is at the heart of our value system, but it is also fundamental to any NHS service provider and protected by a legislative framework. The NHS Act 2006 (Section 242) requires NHS organisations to involve patients and the public in how they plan and run their services, and in planning changes.4 The NHS Constitution5 protects the rights of service users to “be involved, directly or through representatives, in the planning of healthcare services, the development and consideration of proposals for changes in the way those services are provided, and in decisions to be made affecting the operation of those services”.

GOSH also recognises its responsibility in supporting the statutory agenda for children’s health, social care and education outlined in the Government’s Every Child Matters policy programme,6 the Children Act 2004,7 the National Service Framework for Maternity and Children’s Services,8 the Child Health Promotion Programme 2008,9 and the Children’s Plan.10 It also takes account of Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child,11 which states: “Children have the right to say what they think should happen, when adults are making decisions that affect them, and to have their opinions taken into account.”

As an NHS foundation trust, GOSH is a membership organisation that has a corporate responsibility to engage with its members (patients and their families and carers, the general public and staff) in plans affecting the development of its services. In relation to corporate governance, the trust’s redevelopment programme supplies regular reports to the Members’ Council, the Young Peoples’ Forum, the Patient and Family Experience and Engagement Committee, and other stakeholder groups, all of which expect to see evidence of patient and family engagement on any key design projects. At these meetings, we are frequently challenged by our ‘critical friends’ on whether we are doing all we can to engage. Ignoring the insights of these key stakeholders would represent a breach of trust and would also waste a precious resource that can help the selected design team get things right.

Approach

The design brief will outline the vision and aspirations for the next clinical building at GOSH. It is a very significant development not only in scale but also in presence on the street. The architectural response to the design brief will be a major contributor to how the organisation is judged by all stakeholders – but, most importantly, patients and families. It must be designed to put the needs of the child first and provide evidence that the organisation values its people by enabling and supporting staff. This creates the optimum environment for clinical care and research.

Inspired by Jennifer Hands’ presentation at the European Healthcare Design 2015 Congress,12 it was decided to approach the design brief using a model based on the 3Cs – context, content and concept. Early agreement was sought that the concept would derive directly from outputs generated by the Young People’s Forum, a well-established group of patients, ex-patients and siblings of patients aged 11–25 years old, who support the hospital with service development. We were very fortunate to have this fantastic group of ‘expert patients’ with whom to consult. Their personal perspective on the needs of service users, mature attitude and enthusiasm have proved invaluable in the development of numerous hospital initiatives – from patient literature, to the built environment and interior design, to operational strategy.

In architecture, we hear a lot about the importance of designing a building from the inside out. We started with the principle that our brief should also be written from this perspective – not in the literal sense of starting with functional content but in the sense of our values. We needed to express what we are made of and what makes GOSH special. Rather than developing a brief to present to our Young People’s Forum for consultation and comment, we decided that their input should be the creative spark that ignited the entire process.

As bright and articulate as these young people are, we were not interested in engaging their intellect at this early stage. Instead, we wanted to get beyond language and rhetoric and explore something more visceral, identifying the imagery that appealed to them and the emotional impulses that these images stimulated. We were looking to them to generate the visual metaphors, which we could develop and build on with a wider group of stakeholders, and eventually feed into the development of design concepts.

Our first challenge was to create the right conditions to facilitate this process. We needed to provide just enough context and information to ensure that the young people understood where we wanted to get to without imposing any creative inhibition. The next challenge was to develop their creative ideas into meaningful themes, in a similarly uninhibited vein with other hospital stakeholders – including some extremely grown-up strategic thinkers! Finally, the ideas had to be presented within a design brief in a meaningful but non-prescriptive manner that could potentially inspire great design.

Methodology

Resources available to the design brief team included the GOSH arts programme GO Create!, a communication and engagement specialist, and an experienced healthcare planner. This skill set provided an opportunity to develop a tailored approach, anchored in best practice but with the creativity to explore new techniques.

It was, we felt, essential that our methodology employed a balance of tried-and-tested research and insight generation methods alongside more experimental, non-prescriptive techniques. In advance of the phase four project, traditional stakeholder engagement methods were employed in a comprehensive masterplanning consultation. This involved more than 100 meetings and workshops with key clinical and management leads, as well as patient families and their representatives. It also involved a marketing communications campaign to engage patients, families and the Foundation Trust membership, using an interactive web-based platform – allowing children to post comments on our ideas, tell us about their priorities and share ideas of their own.

To inform the design brief for this new building, we created an iterative process starting with the visual metaphors developed by young people, which were explored and developed into design aspirations with a wider group of GOSH stakeholders.

The steps involved were as follows:

- Divergent thinking, in workshop 1: development of visual or surface metaphors with young people using a process inspired by the Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique (ZMET).

- Convergent thinking, in workshop 2: analysis of the workshop metaphors to identify key themes (deep metaphor) and patterns, and begin to understand their implications within the built environment, undertaken by staff and GOSH members’ councillors.

- Co-design inspired by the thematic context, in workshop 3: use of visualisation and play to explore the themes from workshop 2. A diverse group of GOSH staff worked in teams with the Young People’s Forum and GOSH members’ councillors to collaborate on producing a visual brief for their perfect ‘GOSH of the Future’. This included ‘my favourite place’ and the production of ‘picture books’.

- Drop-in arts, crafts and Blokify workshops for children and families, in workshop 4.

- Full analysis of the rich selection of the creative outputs, images, language cues, Wordles and facilitators’ reports produced at each of the four sessions.

- Distance engagement with staff and members’ councillors to obtain their personal stories, which punctuate even the more technical sections of the design brief.

Each of these is explained in more detail below.

Creation of visual metaphors

The creative techniques used in all our workshops were inspired by the Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique (ZMET), a tool to elicit information from respondents based on visual images, metaphors and emotions.13 Developed by Jerry Zaltman in the early 1990s, it ‘digs deeper’ than traditi onal research methods to uncover “hidden knowledge – the underlying beliefs and feelings that influence the behaviours of stakeholders”. Zaltman believed that human beings think in images rather than words. It is a research protocol grounded in clinical psychology, anthropology, linguistics, cognitive neuroscience and sociology.

onal research methods to uncover “hidden knowledge – the underlying beliefs and feelings that influence the behaviours of stakeholders”. Zaltman believed that human beings think in images rather than words. It is a research protocol grounded in clinical psychology, anthropology, linguistics, cognitive neuroscience and sociology.

Astorino Architects used ZMET with patients and families when designing the new paediatric facility at Pittsburgh – UPMC, which opened in 2009 and a year later was hailed as one of the most beautiful hospitals in the US.14 The outputs from the process encouraged the designers to think about giving patients and families a sense of control, especially in relation to the fear of medical environments. This inspired the technical team to hide medical equipment, and provide entertainment, distraction and interaction. Another metaphor – energy – translated into the focus on providing space to recover, connect and recharge.

The ZMET approach is a formal commercial tool, often used in marketing, which involves the use of a trained graphic designer and a psychoanalyst to create a montage of images selected by the participant through the use of image processing software. Bray et al describe how pictures and metaphors “vividly represent the lived experience” and are “both intriguing and compelling”.15 It is perhaps because of this accessibility that healthcare professionals increasingly value the use of art techniques, such as painting, collage and montages, to communicate with patients in a way that isn’t hindered by verbal language.

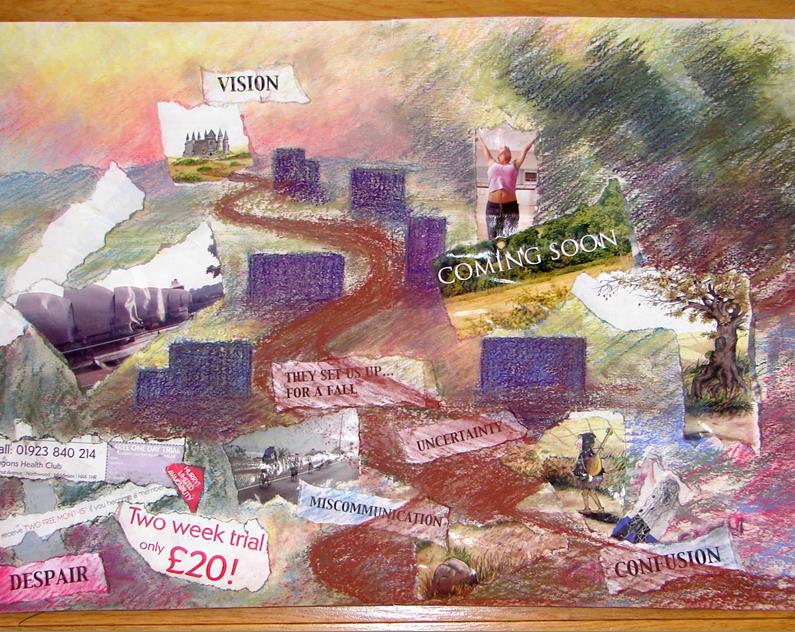

The GOSH design director involved in the phase four project had previously trialled collaging and follow-up interviews as collaborative research tools to identify how best to support clinicians through an earlier hospital design process. The artistic outputs (demonstrated in figure 1) identified powerful metaphors, including a spaghetti head and a storyteller, and expressed the need for a sense-maker and clear navigation of the process. This valuable learning was very effective to help the project team ‘tune in’ to the needs of the building’s key clinical users, and it influenced the way the project was managed.

Workshop 1: engaging the Young People’s Forum

The Young People’s Forum was convened in August 2015 at a special workshop focused on the phase four design brief. To encourage attendees to come to the session, we invited a medical architect to speak about her career experiences, the privilege of touching people’s lives through the design of space and the professional training involved. Next, we asked the young people to start thinking like architects and designers – explaining the context and drivers for creating a new building, and providing an explanation of our aspiration to use a technique, based on ZMET, to inspire them to develop visual metaphors to kick-start the design process.

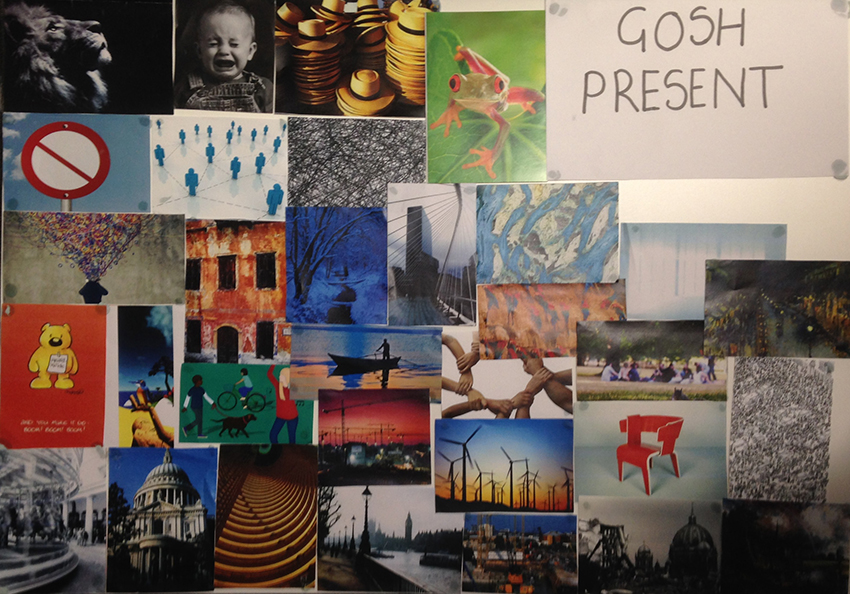

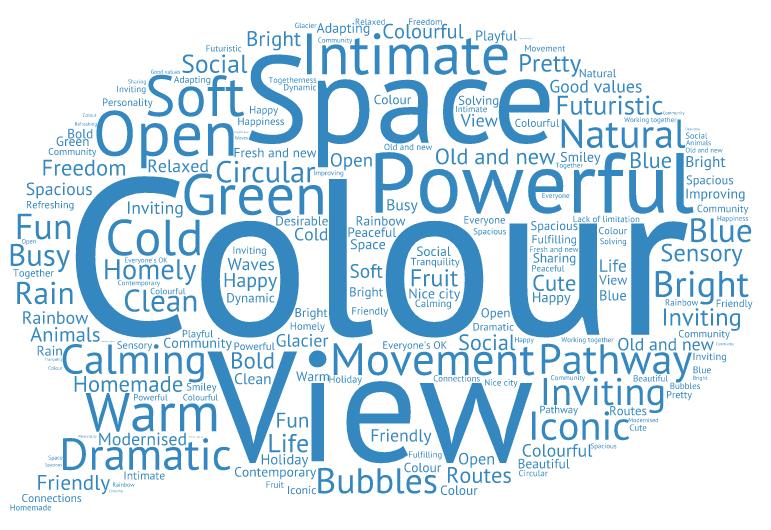

To get the group ‘tuned in’ to self-expression using imagery, we led them through an image selection exercise. We presented them with a wide collection of postcards and asked them to choose one that reflected their memories of GOSH as a patient and one representing their perfect GOSH of the future. Their selections appear in figures 2 and 3. We then asked them to interview each other about the images they had selected to articulate their thoughts further. The facilitator led a group discussion drawing out sensory cues to help engage the group’s creativity, develop the metaphors and elicit the emotional responses. This led to the development of a  Wordle (figure 4), capturing key language used to express the feeling of being in an ideal hospital environment.

Wordle (figure 4), capturing key language used to express the feeling of being in an ideal hospital environment.

The next step was to adopt an image-led approach to produce giant postcards, which would be sent to tell the story of a perfect GOSH of the future, with images and language. The group was invited to imagine the ideal patient and family experience, and work individually to produce a picture for the front of their postcard with imagery demonstrating how that would feel. They were given access to a wide range of art materials, images, colours and textures to produce this picture. The second part of the task was to write a message on the back of the postcard to whoever they might choose – for example, to the building’s architect, to their younger selves or to a family member. This exercise generated the visual metaphors that were developed throughout the project and which appear in the phase four brief.

Importantly, we asked for feedback at the end of the session, also captured in a Wordle (figure 5), which demonstrates the high levels of interest and engagement we saw evident during the session.

Workshop 2: converging the divergent – articulating design aspirations

The work produced by the Young People’s Forum was analysed, explored and set into  themes in a collaborative workshop, which looked at patterns and reflected on the learning that could be applied to the built environment. This work was undertaken by the phase four design brief working group, which incorporated clinical and non-clinical staff and GOSH member’ councillors – who represent patient interests and are elected by our membership of patients and their families and carers, the general public and staff.

themes in a collaborative workshop, which looked at patterns and reflected on the learning that could be applied to the built environment. This work was undertaken by the phase four design brief working group, which incorporated clinical and non-clinical staff and GOSH member’ councillors – who represent patient interests and are elected by our membership of patients and their families and carers, the general public and staff.

The group identified the following key themes:

• nature;

• home away from home;

• technology and sense of community; and

• emotions.

These themes were refined further and expressed as design aspirations for the final workshop:

• magical spaces;

• community, connection and a warm welcome;

• the comforts of home; and

• alive with technology.

Workshop 3: design using play

In October 2015, we recruited a diverse group of staff and stakeholders from across the GOSH community to develop the four design aspirations by working collaboratively in small teams. The methodology for the session was inspired by adapting the principles of design through play, and the following key features of design thinking,16 applied in a workshop scenario:

- collaborative interaction of multidisciplinary and decision-capable teams;

- flexible work space for collaborative work; and

- the design-thinking process of understanding, observing, defining the point of view, ideation, and prototyping.

Participants were provided with a clear set of objectives at the outset, which were to:

- support a co-design process for redevelopment phase four;

- capture stakeholders’ views and experiences to inform a higher-quality design brief;

- produce visual materials to inspire the design process, capturing perspectives from across the GOSH community;

- collaborate and engage our creativity to support better design solutions for these visuals; and

- have fun.

The workshop was set up with a plenary, including the context of the design challenges, the design process, and progress to develop metaphors from the Young People’s Forum’s materials (see photograph, figure 6). A former patient also spoke to the group about how the built environment at GOSH had impacted on her own experience as a patient.

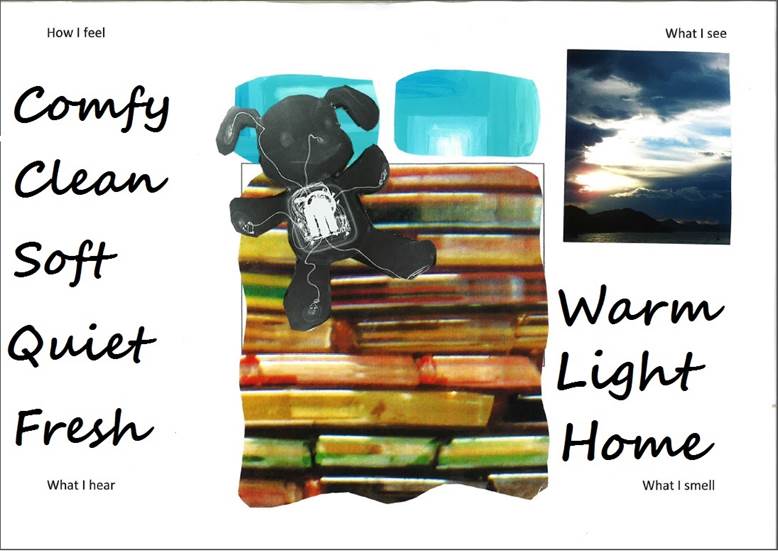

We then embarked on a creative warm-up exercise, visualising our favourite places, selecting images that represent these places, and producing mood boards (see figure 7) that explored sensory cues, including:

- how do you feel?

- what can you see?

- what can you hear? and

- what does it smell like?

For the main creative exercise, participants were put into groups that represented a diverse mix of stakeholders – from clinicians, to ex-patients, members’ councillors, management, and support staff. Each group was allocated one of the design aspirations (‘Magical spaces’; ‘Community, connection and a warm welcome’; ‘The comforts of home’; and ‘Alive with technology) and asked to use any of the creative materials supplied to create a visual representation of their perfect GOSH of the future.

As co-design and collaboration were key to this task, each participant began by sharing their experiences and listening to each other. They were then provided with a wide selection of 2D and 3D art materials, and spent some time working individually, before coming back together to reflect on what they had produced and how to present it.

provided with a wide selection of 2D and 3D art materials, and spent some time working individually, before coming back together to reflect on what they had produced and how to present it.

The session concluded with group feedback and sharing ideas on key issues, such as the importance of tackling fear and isolation, improving the transition between home and hospital life, and promoting wellbeing as well as treating sickness.

Workshop 4: drop-in arts, crafts and Blokify for younger children

We held a drop-in session for children and families in the hospital restaurant to involve them in the process. These sessions involved many of the same features as the stakeholder workshops but, by necessity, they were far less structured. Plenty of staff members were available to speak to individual families about the context and display of materials, which people could browse during their own time. A table-based facilitator was available for each of the traditional creative activities and a Blokify workshop facilitator was also present.

Blokify and 3D printing

‘Sand-box’ style games such as Minecraft and Blokify are increasingly being used in the design world to enable young stakeholders to ‘play’ at designing space. The fact that these games are played on tablet or PC makes them highly  accessible to the ‘digital native’. The educational potential of these games is attracting attention worldwide. In 2015, the South Australian government announced the opportunity for primary-school children to enter a competition to design a park amounting to AU$9m. Recently, the UN Habitat Agency for sustainable urban development also used the tool to engage with young people.

accessible to the ‘digital native’. The educational potential of these games is attracting attention worldwide. In 2015, the South Australian government announced the opportunity for primary-school children to enter a competition to design a park amounting to AU$9m. Recently, the UN Habitat Agency for sustainable urban development also used the tool to engage with young people.

These software applications use building blocks to enable the user to make a virtual product. They are highly intuitive to use and very flexible with a straightforward user interface. Once a design is complete, data can be sent to a 3D printer to create a physical representation of the output.

We invited a professional Blokify facilitator to workshops 1, 3 and 4, because we wanted to extend the art materials available to participants beyond the traditional pen, paper, collage and play dough, and include a digital dimension. Participants’ designs were 3D-printed after the session and photographed, along with the other creative outputs.

Project outputs

The rich visual outputs from the workshops are really inspiring, providing insight into our stakeholders’ priorities that couldn’t be captured so powerfully in a standard textual format. Within the metaphors they selected, several recurring themes emerged; these were then built on and the resulting ideas grouped into a meaningful framework for the design brief.

We have also collated a wide range of written phrases, stories and language cues, which demonstrate a wide range of stakeholders’ aspirations for the building. These contain valuable learnings that are useful not only for a phase four design team but also for all GOSH staff involved in the redevelopment and patient experience programmes.

Children of all ages felt able to express their ideas assertively, articulately and meaningfully. Their input has ensured that the design brief includes extremely rich visual and verbal input, providing the insight that can fuel and inspire the design process.

Some of the key themes that kept emerging included:

- Children generally prefer spaces that don’t look too functional or clinical, and that stimulate their imagination.

- The necessity of spending time away from home makes access to comforting spaces essential. Tackling fear and isolation, and fostering continuity and calm help children in unfamiliar surroundings, or those having to move regularly from setting to setting.

- Nature and a sense of connection with the outdoors are vital to fostering a sense of freedom and wellbeing. Being able to spend time outside, however sick you may be, was considered a high priority.

- Good Wi-Fi connectivity helps patients feel less isolated from their friends and families, and access to dynamic content and technology is essential to their wellbeing. Children and young people are very comfortable with technology and have sophisticated ideas about how it can be integrated in the built environment.

- Young children are consistently drawn to easily recognisable characters or motifs, such as cartoon characters, animals and vehicles.

- Our older, long-term patients often tell us that they don’t want to be defined or constrained by their conditions and that they want to be treated as adults. They also remind us that childhood is dynamic, that what appeals to young children will not always suitable for teenagers.

- Lighting, colours, food and smells (good and bad) play a big part in the patient experience, and they dominated memories of being in hospital for some of our older patients.

The insights generated throughout the process were extremely varied – ranging from the inspirational, creative and abstract, to the solid, practical and technical; for example, one particularly powerful visual metaphor postcard was annotated by a young person with the following text:

“There is a big sun for lots of light and to represent the children’s happiness. There’s grass and trees to give the children scenery and to make them feel free and out in the open. There are balloons, which show fun and happiness, and they are clustered together showing friendship and community. There is a large fish tank for the children to view and show them something exciting, and there is a craft table for the younger children to play and express their thoughts.”

Parents and carers also provided a rich source of ideas about how to create an engaging environment, articulating the importance of sensory play and educational features that help their children explore the world in spite the constraints of a hospital environment. They told us that being able to see their children playing at all times means they can relax because they know they are safe. They were also able to provide lots of useful insights into the absence of user-led design on their day-to-day experience. One example from the phase 4 design brief comes from a mum’s personal account of several stays at GOSH with her son over many years. On one stay she had to do a daily clothes wash to minimise the infection risk to her child, who was recovering from a transplant. She recalls how much of her precious little respite time away from her son’s bedside was taken up with running to far-flung laundry facilities. She also describes how situating parents’ tea-making facilities away from the ward made her feel less welcome and required her to disrupt staff to get ‘buzzed’ back in.

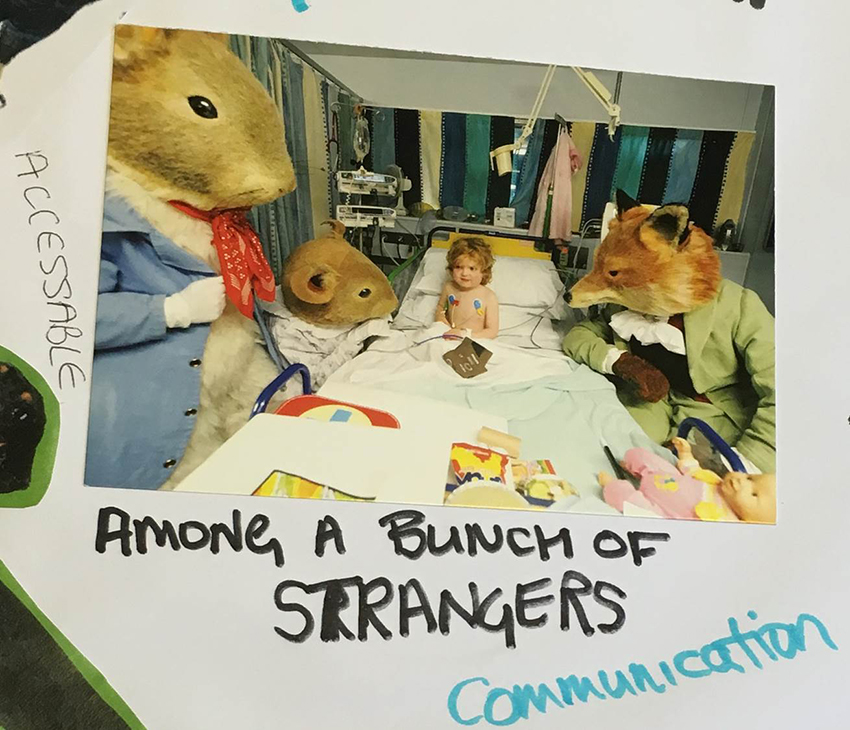

Staff insights demonstrated the importance of technology and spaces that support them in being fleet of foot, in order to deal with the problems that arise constantly throughout a shift. Their input also spoke volumes about their empathy for the isolation that patients and families can suffer. This is beautifully embodied within an image at the centre of a collage, showing a young child looking anxiously on at a crowd of human-sized animals surrounding her hospital bed (see figure 8).

A secondary output from this advocacy process is the high levels of interest and engagement in the building that are now evident throughout the GOSH community. This motivation to engage will be invaluable as the project is progressed to the RIBA design competition stage. The selected design team will be able to harness this sense of cross-organisational ‘ownership’, both among GOSH staff and our wider stakeholder network, and ensure users’ needs continue to be paramount.

Project learnings and implications

The aim of this project was to ensure that shortlisted design teams could start out on their journey armed with the rich insights generated from our diverse stakeholders. It has been our job to represent their interests and communicate these to our partners, ensuring that the needs of patients, families and staff are kept at the heart of the design process from the outset.

Since the new building doesn’t yet exist – even on paper – it won’t be possible to assess whether this project has succeeded or failed in its objectives for many years to come. The ultimate test will be the response from the market, as we move forward to the design competition. Undoubtedly, though, we have been successful in setting the tone for a design project that has the patient and family experience at its centre. We have also started to express what this means with a powerful collection of images and words. There have also been other by-products and learning opportunities that have arisen from the process.

Generally, the strategy of using innovative techniques for stakeholder engagement has delivered high-quality visual materials. This has not, however, happened in all cases and there is some useful learning to take forward; for example, although participants enjoyed the Blokify workshop activity, and it was undoubtedly useful to engage younger visitors, the outputs from these sessions were far less useful to the design brief team than the postcards and other items. The 3D print-outs produced were too simple and monolithic to represent the design aspirations that were expressed to us verbally or in 2D art outcomes.

In part, this may be because we failed to brief the facilitator adequately or we misunderstood how long it would take participants to produce something that looked distinctive enough to represent a design aspiration. Perhaps an architect would be able to recognise spatial rhythms and massing that could translate into a design concept. Regardless, this tool did not prove to be suitable to support our objective to generate material to develop design metaphors.

Co-design projects are, by their nature, resource-intensive. It is important to engage with a sufficient number and variety of stakeholders to ensure the process represents all building users. Campaigns are required to advertise engagement events and recruit participants. Each engagement interaction has to be carefully planned and tailored so that stakeholders receive sufficient input to educate them and sufficient time to consider and articulate their responses. Finally, an analysis and feedback process is required to assess feedback and demonstrate to stakeholders that the organisation has genuinely listened.

The design-thinking blueprint requires a style of user engagement that is more involved than standard NHS services co-design. Moreover, pressures on the NHS are such that demonstrating a return on investment, in time and resource, is essential. In this sense, the project has raised the stakes for the project team – increasing the requirement for a final output that delivers not only on the patient-experience agenda but also in the wider context of quality and efficiency.

The other by-product of early engagement with building users is that it sets an expectation among key stakeholder groups – both that they will continue to be consulted at all stages of the process and that they will see evidence of their personal input in the design process. We have undoubtedly experienced a sense of ownership from our stakeholders, which we will need to respond to as the project progresses. Genuine engagement is always a two-way dialogue involving information, involvement and feedback. It should always be considered as a continuous journey – a modus operandi – and never as an isolated project.

We have embraced this ambitious project precisely because we feel that stimulating this sense of stakeholder expectation is crucial to a quality outcome. We want to see continued advocacy and engagement throughout every strand of the project. We hope and expect that our stakeholders will continue to hold us to account to ensure their needs are kept at the centre of the process, and that we live up to GOSH’s guiding principle: ‘the child first and always’.

Authors

Stephanie Williamson MA is deputy development director at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust. Louisa Desborough BA, MCIPR is communications associate for both the Trust and Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity.

Acknowledgements

The redevelopment programme at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust is supported by Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity.

References

- Harris Interactive. Charity Brand Index 2015. London: Third Sector Research, Haymarket; 2015.

- Superbrands UK. Consumer Superbrands 2016. 2016. Available from: http://www.superbrands.uk.com/results [accessed 31 May 2016].

- Design thinking. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Design_thinking [accessed 26 April 2016].

- National Health Service Act 2006. Chapter 41. London: The Stationery Office Limited; 2006.

- The NHS Constitution for England. Department of Health. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-nhs-constitution-for-england [accessed 31 May 2016].

- Every Child Matters. London: The Stationery Office Limited; 2003.

- The Children Act 2004. Chapter 31. London: The Stationery Office Limited; 2004.

- Department of Health. The National Service Framework for Maternity and Children’s Services. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-service-framework-children-young-people-and-maternity-services [accessed 31 May 2016].

- Department of Health. The Child Health Promotion Programme 2008. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130401151715/

http://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/DH-286448.pdf [accessed 31 May 2016]. - Department for Children, Schools and Families. The Children’s Plan 2007. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-childrens-plan [accessed 31 May 2016].

- Fact sheet: a summary of the rights under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Unicef. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/crc/files/Rights_overview.pdf [accessed 31 May 2016].

- Hands, J. Creating flexibility in acute inpatient ward design. Presentation delivered at European Healthcare Design 2015.

- Zaltman, O. Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique. Available from: http://olsonzaltman.com/zmet [accessed 31 May 2016].

- Astorino, L. Metaphorical design method. Architecture Week: Culture. 2003. Available from: http://www.architectureweek.com/2003/1001/culture_1-1.html [accessed 31 May 2016].

- Bray, JN, Lee, J, Smith, LL and Yorks, L. Collaborative Inquiry in Practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2000.

- Hasso-Platner Institut. What is design thinking? Available from: http://hpi-academy.de/en/design-thinking/what-is-design-thinking.html [accessed 31 May 2016].

Organisations involved