Healthcare / Social determinants of health

Comment

Value, vacancy and vision: Reimagining occupation principles to drive efficiency across the NHS estate

06 Feb 2024 | 0

More radical and systemic approaches to exploiting vacant or under-utilised estate could be implemented to better support the health prevention and health creation agendas, population health outcomes, and the healthcare economy. Harry Dodd investigates.

About 15 per cent of the entire NHS primary care estate is owned and managed by NHS Property Services and Community Health Partnerships, equating to some 3000 buildings.1,2 The majority of these are occupied by GPs, whose rent is reimbursed by commissioners as part of the provision of NHS primary care services and a proportion are occupied by community services funded by integrated care boards. Many of these buildings, however, are known to be vacant or underutilised.3

The reasons range from fallen-through occupancy arrangements as part of a new-build proposal, to expired leases, market saturation, and/or a lack of desirability leading to an inability to re-let previously occupied space. Whatever the reason, the rent and maintenance bills for all this vacant space must be picked up by those responsible for primary and community care commissioning: integrated care systems (ICSs).

Formed in 2022, ICSs were handed a remit that extended beyond primary care and clinical services – a limitation of the now abolished clinical commissioning groups – giving them responsibility for place-based, cross-organisational commissioning.

Stemming from Sir Michael Marmot’s seminal 2010 publication, ‘Fair society, healthy lives’,4 ICSs are the commissioning manifestation of an increasing understanding of how ‘social determinants’ can have a greater impact on population health than clinical services. The report highlighted that some 40 per cent of all presentations to the NHS are avoidable,4 while 70 per cent of all existing health conditions are chronic.5 We may be living longer but generally in poorer health, with increasing inequality in health access and outcomes. Indeed, nationally, rates of diabetes, obesity, loneliness, and depression are higher than ever before.6

At the core of ICSs is the concept of partnership working with other public and third-sector services to help tackle these complex challenges. Their main aims are to:

- improve outcomes in population health and healthcare;

- tackle inequalities in outcomes, experience and access;

- enhance productivity and value for money; and

- help the NHS support broader social and economic development.

The reference to population health is an inherent acknowledgement of the disparity of care between the richest and poorest parts of the country, while it also gives a direct nod to the role that prevention and community-based care plays in supporting the financial sustainability of the NHS. The final aim highlights the link between ‘health’ and ‘wealth’, calling on commissioners to better harness the ‘hard and soft’ functions of the NHS to improve the economy, both locally and nationally.

Underpinning these lofty ambitions has been a fundamental overhaul in the funding mechanism for commissioners.7 Previously, primary care, secondary care and all other commissioning funding streams were considered separately. The formation of integrated care boards (ICBs) saw the advent of ‘the single budget’, enabling decisions to be taken on which services in which locations should be prioritised across a given geography. The thinking was that this would enable commissioners to redress the traditional disparity in funding between primary and secondary care services, supporting the prevention agenda, and thereby reducing presentations to secondary care, while freeing up acute services to specialise increasingly on more complex issues.

So why is the opportunity to co-locate complementary preventive and treatment services often still being missed across the estate?

The challenge is that commissioners and the NHS own no (or very little) property in the community. Consequently, efforts to deliver changes that truly support prevention services in this setting often continue to be met by third-party legal, governance and financial barriers.

Irrespective of ownership, a long legacy of underfunding across the primary care estate8 means that much of it is wholly inappropriate for a service shift of this kind anyhow. Much of our health infrastructure is still geared up to provide an NHS-led clinical intervention to challenges that some would debate are better addressed through social intervention.

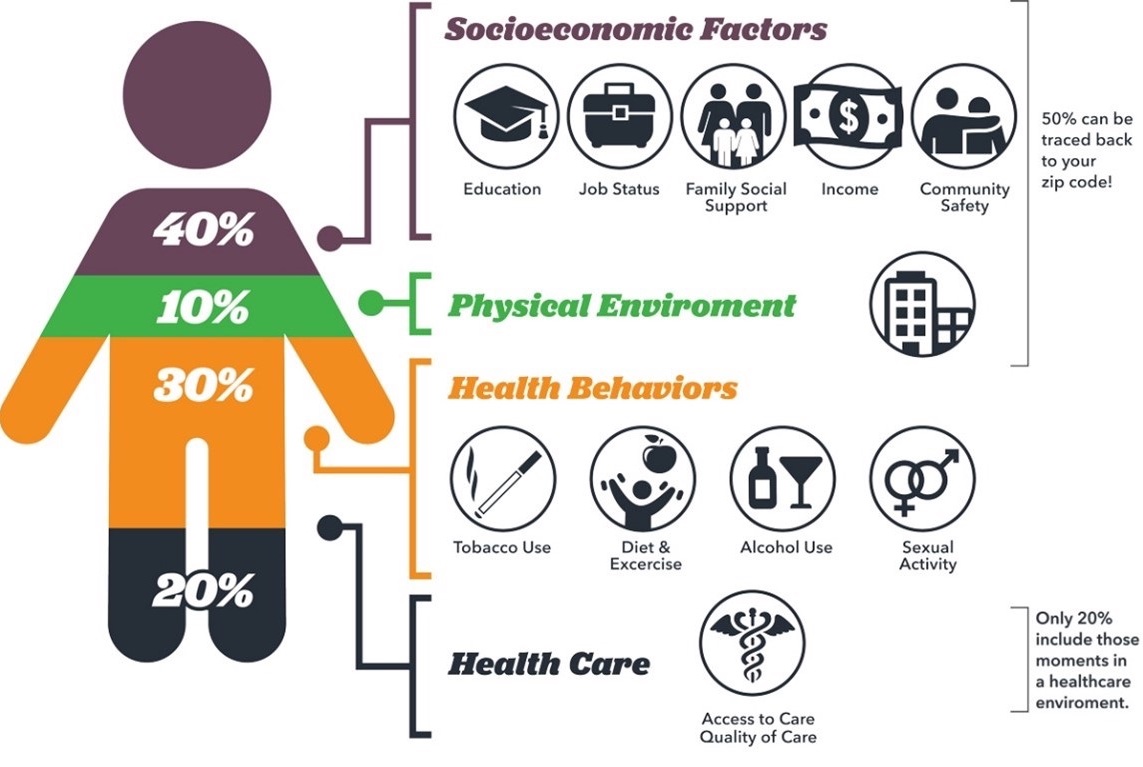

How, then, can commissioners proactively support the remaining 80 per cent of non-clinical influencers on health outcomes (see figure 1)?

While there are examples of good work already happening in this area, such as NHS Property Services’ interactive Social Prescribing Map,9 which helps join patients up with complementary social support services, how can more radical and systemic approaches to better utilising vacant or under-utilised estate be better implemented to support population health outcomes and the healthcare economy?

Informed by population health data, commissioners could work with services that seek to tackle specific high-prevalence, high-cost local health issues, such as frailty, child poverty or homelessness, and offer co-located space with existing health partners for free, or at significantly reduced rates with a view to supporting a reduction in presentations to the NHS.

Modelling this approach comes up with some surprising returns on investment for the health economy across relatively short time periods, while aligning directly with each of the four aims of ICSs stated above. It’s estimated that:

- In areas with a high prevalence of frailty, integrating third-sector trip and fall prevention services with primary care services could achieve cost neutrality for commissioners (offering up the space for free) after avoiding only two admissions to hospital within a 12-month period (where these would otherwise result in fracture services). Half of those aged 80 and over (about 1.5m people) will fall at least once a year, and 5 per cent of these lead to a fracture and hospitalisation.

- In areas with high child poverty, avoiding only four hospital admissions a month for conditions relating to cold and damp housing was modelled to achieve cost neutrality, where space was offered to legal charities and/or local authority housing services, as well as food and clothing banks to support nutrition and warmth. Poverty affects 4.2m children in the UK (29 per cent), costing the NHS an estimated £3.8bn annually.

- Avoidance of 17 admissions to hospital a year where patients have ‘no fixed abode’ were modelled in a given geography as necessary to achieve cost neutrality to co-locate homelessness wraparound support and prevention services in a community setting. There are around 271,000 homeless people in England, according to Shelter. The rate of admissions to hospital is more than fourfold higher in the homeless population, at a cost of £85m per year.10

Of course, all this depends on a string of interdependencies: funding for fit-outs; workforce availability; alignment of services with prevailing local health needs, etc. But any strategy document should start with a vision, and these are short-term challenges that must be overcome in order to realise long-term financial and operational efficiencies.

Next steps

Through our own experiences in supporting clients in this space, we suggest the process of translating strategic vision into action be delivered via four key steps:

- Establishing organisational consensus and conviction to support the vision for change

In some localities, securing investment for such initiatives involves a significant culture shift for a system accustomed to a significant funding discrepancy between primary and secondary care. In approaching this change, we must employ a ‘whole system economics’ approach to health, wellbeing and patient outcomes. Some clients have secured agreement within their ‘single budget’ governance structures to link success achieved via this initiative with year-on-year capital allocations to primary care – so a demonstrable efficiency saving of, say, 10 per cent as a result of this work will lead to a corresponding 10 per cent of the capital budget, and so on.

There are also many exemplars of successful work already implemented or in progress in this space, including flexible occupation models; agile service mixes; flexible room typologies; and community-led initiatives that generate local ‘ownership’ to combat vacant and under-utilised spaces, such as the Limelight Centre in Trafford. The expression of execution might vary to meet local need and resources but, ultimately, each initiative is united in its contribution towards building social resilience within communities and reducing dependency on NHS services.11

- Legal considerations – leases, licences, nomination rights and rents all need to be assessed, and the ‘levers’ in any given case understood, driving maximum optimisation of assets through novel approaches

Commercial ‘landlord and tenant’ occupation arrangements only go so far. This traditional model is inflexible, giving a defined demise (or defined floorspace, i.e. a fixed number of rooms as specified in the lease) to a provider for a set period of time – normally 20-plus years to cover investment risk – to undertake defined activity. Restrictive covenants and limitations on sub-letting and/or wider nomination rights often make creative and agile service commissioning solutions impossible, or at least very challenging, over the same period.

Instead, the commissioner needs to take a leading role in supporting and negotiating occupation solutions that are relevant for existing and future service delivery needs. This doesn’t mean they need to take on leases directly, which can have an impact on capital departmental expenditure limits (CDEL), but they should look to use their soft purchasing power and influence to bring organisations together. Their access to ‘big data’ will play an important role, as well as giving ‘permission’ for non-clinical activity to take place in these buildings, which they ultimately reimburse.

Archus has supported NHS England and commissioners in the development of ‘lease-lite’ occupation solutions – already adopted in practice by a handful of integrated care boards – which not only allow for changing health needs and corresponding complementary services but also include provisions to ‘claw back’ space that is being under-utilised within the lease term. This negates the risks of ‘white elephant’ vacancies and voids if properly administered.

- Building occupation – embedding a strong building user group culture through the establishment of governance and protocols

Successful building management is much more than an effective facilities management strategy. It’s the intangible ‘culture’ of a building that makes it either welcoming or austere, clinical or community, ‘for us’ or ‘for them’. Too often, in its drive to standardise or ensure parity of treatment, the NHS can hegemonise local variation and responsiveness to community issues that actually make the difference.

Strong, cross-organisation leadership of any community-focused asset is key. Clinical activity is the NHS’ bread and butter and should remain a core focus of any such asset. But to achieve success, community providers need an equal – or, at least, a genuinely proportionate – seat at the table, and their contribution to ‘wellbeing’ needs to be understood as a contribution to ‘health’.

Working with two different clients in the South West and the Midlands, as well as with NHS England, Archus has developed a template ‘building protocols’ document, which aims to put in place effective building governance and sets out the rules for effective integration of health and wellbeing services that serves to treat more patients in primary care or in the community. This has been tested with GPs and adopted in various locations, demonstrating its applicability. Thought has also been given to the roles and responsibilities of the building manager – the custodian of operational culture – feeding into a standard job description for clients’ consideration. Start-up facilitation workshops and ‘building user group’ initiation and/or refresher sessions can help ensure the correct working cultures are understood and embedded by all partners from day one.

- Monitoring

Monitoring success in prevention – i.e., what didn’t happen – is notoriously hard. One solution is to identify high-impact patient pathways that traditionally result in referral locally, and to track changes in admission rates over time. It’s not perfect, and causality cannot be proven conclusively, but it’s a start. There are, of course, wider proxy indicators of success, such as patient satisfaction ratings; waiting times; population health data; and indices on the level and type of partnership working beyond the NHS. The key is monitoring over time, as results may not be evident immediately.

What is certain is that given the changes in morbidity and acuity seen in the last 75 years, a focus on social interventions, as well as medical ones, is what will ensure the NHS continues to serve modern society most effectively. By collaborating with healthcare property owners to reimagine the way the health estate is occupied, integrated care systems will be able to deliver their strategic aims and harness the accumulating power of improved population health.

About the author

Harry Dodd is an associate director at Archus, a consultancy with expertise in the planning and delivery of healthcare infrastructure and an in-depth understanding of the relationship between estate and service delivery. Archus is currently working with a number of clients on planning and implementing solutions that embed a change in the traditional ways of working, and which capture the benefit of an estate geared up for both preventive and clinical interventions over time.

References

- House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts. (2019). NHS Property Services. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201919/cmselect/cmpubacc/200/200.pdf

- Community Health Partnerships. CHP services. [Online]. https://communityhealthpartnerships.co.uk/tenant-hub/chp-services/

- The King’s Fund. (2013). NHS buildings: Obstacle or opportunity? https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/reports/nhs-buildings-obstacle-opportunity

- UCL Institute of Health Equity. (2010). Fair society, healthy lives. The Marmot Review. https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-full-report-pdf.pdf

- Cottam, H. (2018). Radical Help: How we can remake the relationships between us and revolutionise the welfare state; Virago Press.

- NHS England. Healthy New Towns. [Online]. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/innovation/healthy-new-towns/

- NHS England. (2018). Overview of integrated budgets for ICPs. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/overview-of-integrated-budgets.pdf

- Department of Health and Social Care. (2017). NHS property and estates: Naylor review. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-property-and-estates-naylor-review

- NHS Property Services. Find a social prescribing site. [Online]. https://www.property.nhs.uk/about/social-responsibility/social-prescribing/interactive-map/

- Himsworth, C, Paudyal, P, and Sargeant, C. (2020). British Journal of General Practice. https://bjgp.org/content/70/695/e406#

- NHS England. (2019). Putting health into place: principles 1-3. Plan, assess and involve. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/phip-1-plan-assess-involve.pdf

Organisations involved