Healthcare / Evaluation and performance

Towards a quantitative sustainability assessment of hospital buildings in Belgium

By Milena Stevanovic, Rense Vandewalle, Stephane Vermeulen and Karen Allacker | 16 Nov 2018 | 0

This paper focuses on a new quantitative sustainability assessment method for hospital buildings in Belgium.

Authors of scientific paper:

Abstract

Concerns about the sustainability of healthcare facilities have been reflected in a proliferation of certification schemes, such as BREEAM, LEED and DGNB. Although these schemes are easy to implement, the subjective benchmarking on which the sustainability assessment is based leaves doubts as to whether the use of these schemes leads to truly sustainable buildings. Recent years have seen a shift towards sustainability assessment in the construction sector using approaches based on lifecycle thinking.

Methods: This paper focuses on a new quantitative sustainability assessment method for hospital buildings in Belgium. The developing process was based on learnings from a previous study when the Belgian MMG+_KULeuven tool, predominantly developed for residential buildings, was applied to the general hospital Sint-Maarten in Mechelen. The current method for hospital buildings integrates lifecycle assessment (LCA) and lifecycle costing (LCC), allowing building practitioners to track simultaneously the environmental impacts and financial implications of a hospital building. It’s possible to compare up to six scenarios, taking into account the designer’s choice of building element materialisation. The conceptual design parameters relevant to determine the quantity of building elements include number of hospital beds, square metres per bed, number of floors, and hospital building lifespan. The method allows for hospital energy modelling in the conceptual phase.

Results: Aside from scores per impact category for environmental impacts, the method has an aggregated single-score indicator, expressed in a monetary value (Euros). This makes it possible to couple both the environmental and financial costs, giving the total cost of the hospital building. Visualisation of the results is provided, both per square-metre floor area and per hospital bed. Graphical visualisation is included at building element level.

Conclusions: The method presented provides rough estimations of environmental and financial costs of a hospital building during the early design phase. It also serves for detailed calculations when more data become available along the design process. By coupling the LCA and LCC with the energy modelling from the early design phase, the method presents a powerful tool to optimise hospital building performance in environmental and financial costs, as well as overall energy consumption.

Keywords

That hospitals are highly dependent on natural resources is not a new fact. The idea, however, that buildings focused on healing the ill are simultaneously causing important environmental and health burdens is rather paradoxical. Concerns about the sustainability of healthcare facilities have emerged over the past decennia, which led to an increasing interest in the way these buildings are designed and operated.1

Today, these facilities are challenged in reconciling the decrease of their environmental impacts, while providing affordable and quality medical care for everyone. Consequently, efforts to ease the sustainability evaluation of hospitals has been reflected in the proliferation of certification tools developed specially to address healthcare buildings. The eminent ones include BREEAM, DGNB, LEED and Green Star. Most of these tools use a qualitative approach, ie, they consist of a list of measures that are assumed to be sustainable and work on the principle “the more measures taken, the more sustainable the building”.1 Although their ease of use from the first design concept has gained them popularity among building practitioners, the subjectivity in their assessment approach to sustainability has raised doubts as to whether using these schemes leads towards truly sustainable buildings.2 This awakening served as a turning point in realising that a quantitative approach based on a lifecycle-thinking perspective seems more appropriate when tackling the sustainability of hospital buildings. Until now, however, a method relying on such an approach hadn’t been developed.

Scope of the study

The objective of this paper is twofold. The first is to develop a new sustainability assessment tool for hospital buildings in the Flemish region using the lifecycle assessment (LCA) to track the environmental performance, and lifecycle cost (LCC) for financial implications. Secondly, to integrate from an early-design phase to a more precise energy consumption calculation, the use of the parametric design is explored. The following describes the applied methodology, tool description and results. Finally, the conclusions discuss the major outcomes of the paper and provide steps for further research.

Method

Lifecycle assessment

Under the proposed method, the environmental impacts of a hospital building are assessed over its entire lifecycle, using the internationally standardised methodology called lifecycle assessment (LCA).3 The approach to analysing the environmental implications of the hospitals is based on the Belgian MMG (Milieugerelateerde Materiaalprestatie van Gebouwelementen) LCA method, developed for assessing building components and buildings.4 The MMG method was converted into an Excel-based tool at the architectural engineering research division of KU Leuven, referred henceforth as the MMG+_KULeuven tool.

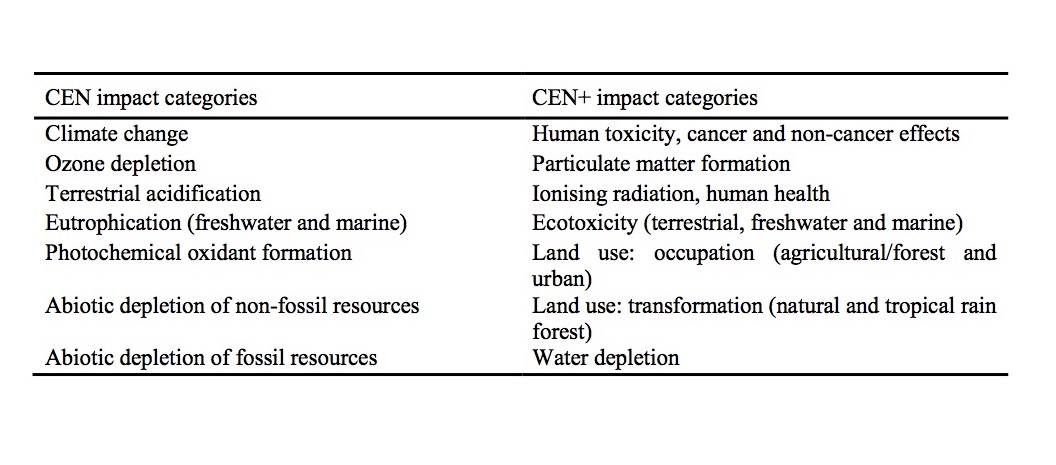

Under this method, the considered environmental impacts are in line with the impact categories defined by the CEN TC350 standards5 and are referred to as CEN indicators. These include: global warming potential; depletion of the stratospheric ozone layer; acidification of land and water sources; eutrophication freshwater and marine; photochemical oxidant formation; and abiotic depletion of non-fossil resources. Furthermore, the MMG method covers an additional list of other impacts based on the International Reference Life Cycle Data System (ILCD) Handbook6 and decided in consultation with the Flemish-Belgian policymakers. These additional impacts are referred to as CEN+ indicators and include human toxicity (cancer and non-cancer effects), particulate matter formation, ionising radiation (human health), ecotoxicity (terrestrial, freshwater and marine), land use: land occupation (agricultural/forest and urban), and land use: land transformation (tropical rainforest) (see Table 1).

The covered lifecycle stages of the hospital include the initial, the use and the end-of-life (EOL) stages. The production stage takes into account the extraction of the raw materials and their transport to the production site, transfer to the construction site, and construction activities. The use stage includes processes related to cleaning, maintenance, replacement of components, and operational energy use. Lastly, the EOL stage includes the demolition activities, waste transport and waste treatment (see figure 1).

Under the MMG method, in addition to the characterised scores for each impact category, an aggregated single score indicator, expressed in a monetary value (Euro), is calculated. This indicator is referred to as external environmental cost.7 These costs are calculated by multiplying the characterised environmental impact with their specific monetary value; by adding these sums up, the overall environmental cost (single score) is obtained.4

Lifecycle costing

The financial implications of a hospital building are considered in the lifecycle costing (LCC) approach, a well-known economic calculation method to estimate the costs related to different life stages of a building.9 As discussed in Trigaux et al,9 the costs taken into account cover the investment cost (ie, material, labour, and indirect costs for initial construction), cleaning, maintenance, replacement, and energy costs during the use phase, and the costs for demolition and waste treatment during the EOL stage. The financial data of the building elements are mostly based on the Belgian cost database ASPEN.10,11

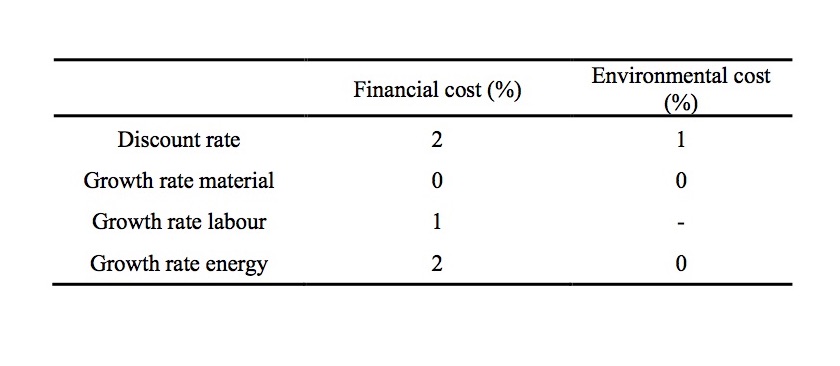

To calculate the financial cost over the building’s lifecycle, the sum of the present values of all costs throughout different lifecycle stages is taken into account. The economic parameters are based on the Belgian statistical data summarised in Table 2.

To calculate the financial cost over the building’s lifecycle, the sum of the present values of all costs throughout different lifecycle stages is taken into account. The economic parameters are based on the Belgian statistical data summarised in Table 2.

The considered building elements include: cellar floor; floor on ground; cellar wall; external wall; loadbearing internal wall; non-loadbearing internal wall; storey floor; stairs; column (free-standing); flat roof; windows; doors; heating; cooling; ventilation installations; pipes; high-rise elevator; low-rise elevator; lighting installations; and electricity cables.

The databases containing the predefined technical solutions – ie, compositions of each of the aforementioned building elements – were extracted from the previous study by Stevanovic et al,1 where the existing MMG+KULeuven tool was applied to the general hospital Sint-Maarten in Mechelen. Databases for floors, external walls and roofs were extended with new solutions based on different materials used for various hospital projects that VK Architects & Engineers has been working on.

Parametric design for operational energy consumption

The early-design stage represents a crucial decision-making phase, where all the design requirements and factors, such as building geometry, space organisation, facade and other parameters, will be defined.12 With hospitals requiring high amounts of energy and electricity to operate, and targets to meet the 2010 European Directive on the Energy Performance of Buildings (EPBD),13 taking into account energy efficiency at the early-design stage is of utmost importance. Given the complexity of hospital buildings emanating from the fact they house different building typologies in the same facility, using the parametric design to optimise the hospital energy performance seems to be a fitting solution. This is reflected in studies of Shikder et al14 and Sherif et al,15 where parametric optimisation is used for daylight-window configuration in patient rooms.

Early-design stage and parameters for hospital building geometry

The reduction of patient beds and acute care in Flanders led to hospitals in the same network merging into one new building.1 This movement resulted in a vast majority of calls for competitions to design new hospitals around the Flemish region. Most of the time, the early-design phase of a hospital facility project will occur at the competition level. At this stage, the building practitioners have to comply with the well-established parameters that serve to define the building geometry, the energy necessary for spatial heating, the electricity for cooling, ventilation, lighting and medical technical equipment, as well as the water consumption of a hospital. These include inputs, such as the types of departments required, square metres per department, and the number of accredited beds.i

VIPAii has defined the number of square metres per hospital bed, based on which the hospital can ask for governmental subsides.16,17 This number and the predefined square metres per hospital department, serve to calculate the total gross floor area of a building.

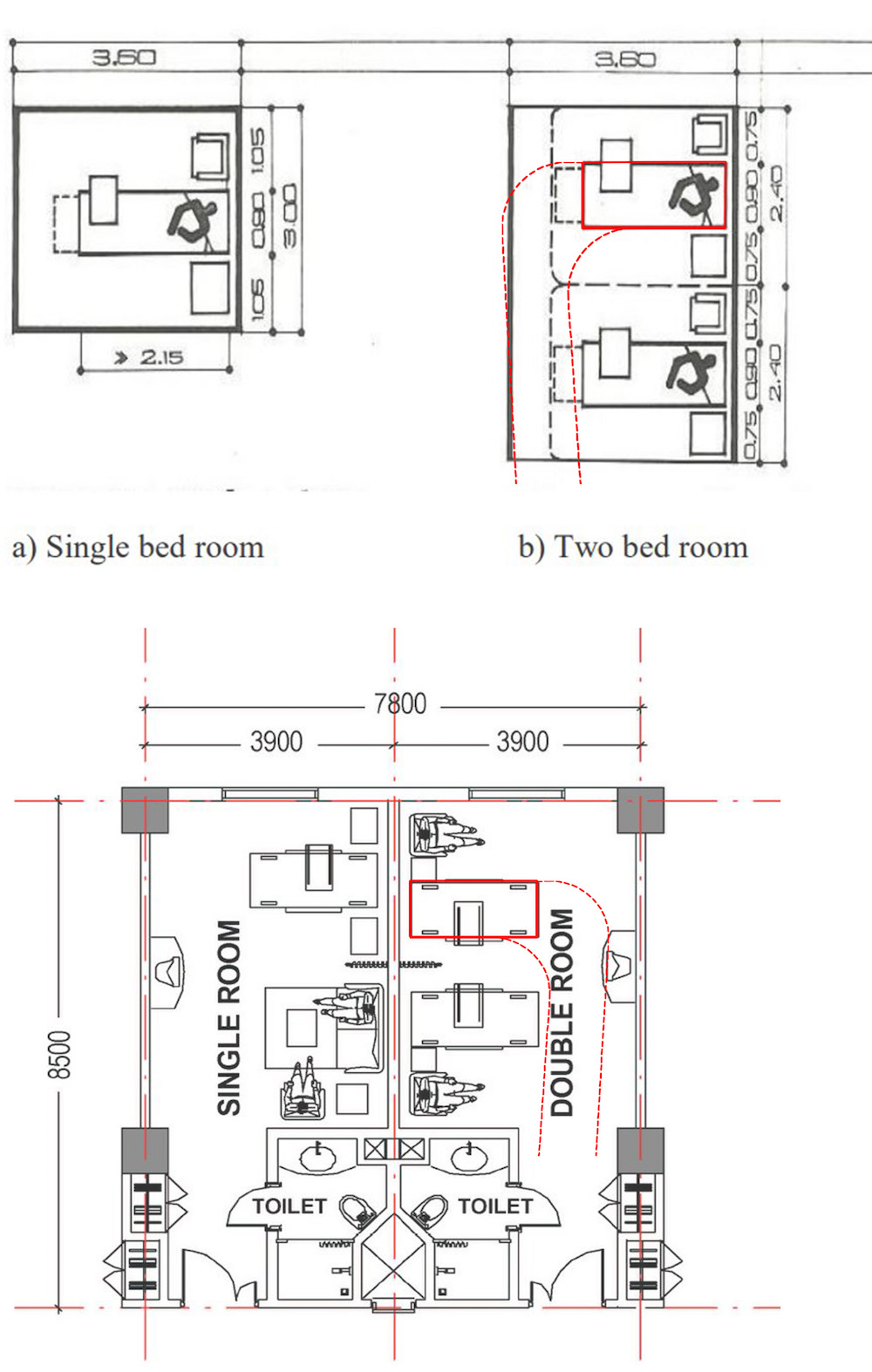

Another important parameter that will influence the geometry of a hospital building is the construction grid. Typically, in practice, grids of either 7.2 or 7.8 metres are used. The first one is a well-known structural grid based on the minimum dimensions for a single patient room of 3.6 (width) x 3.7 (depth) metres, within which, it has been established, most activities can be carried out at the bedside.18 In case of a double patient room, when circulating with beds in and out, these dimensions do not suffice. The grid of 7.8 metres was introduced based on the experience in practice, owing to technological advancement and the changing bed size (see Figure 2).

Another important parameter that will influence the geometry of a hospital building is the construction grid. Typically, in practice, grids of either 7.2 or 7.8 metres are used. The first one is a well-known structural grid based on the minimum dimensions for a single patient room of 3.6 (width) x 3.7 (depth) metres, within which, it has been established, most activities can be carried out at the bedside.18 In case of a double patient room, when circulating with beds in and out, these dimensions do not suffice. The grid of 7.8 metres was introduced based on the experience in practice, owing to technological advancement and the changing bed size (see Figure 2).

Parameters for spatial heating energy calculation

To calculate consumptions of energy for heating, the combination of the 3D computer-aided design application software Rhinoceros 6 and its plug-ins, Ladybug and Honeybee, is used. In addition, a visual programming language, Grasshopper3D, which runs within the Rhinoceros programme, is used to build generative algorithms to create a 3D geometry. Ladybug is a recently developed environmental plug-in for Grasshopper3D. It benefits the parametric platform of Grasshopper to allow the designer to explore the direct relationship between environmental data and the generation of the design through graphical data outputs that are integrated with the building geometry.21 Honeybee is the extension of Ladybug, which enhances users’ ability to work directly with Radiance, Daysim, and EnergyPlus.21

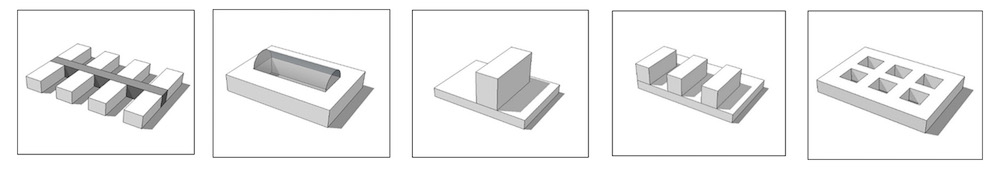

The parameters necessary to calculate energy consumption include: the type of hospital building emanating from the typology defined in Prasad22 (see Figure 3); the climate data for the context in which the building is designed; orientation of the building; spatial organisation of departments; floor height; and the heat transfer co-efficients (U-values) of the heat-loss surfaces.

Tool description

Dashboards for environmental and financial cost calculation

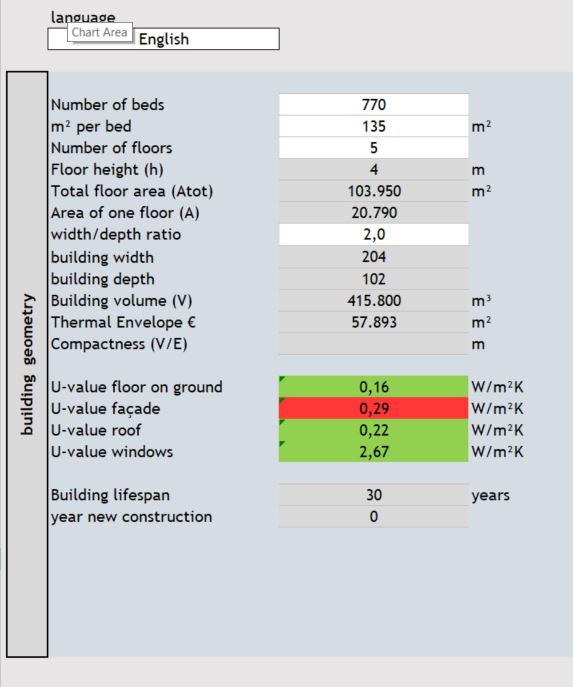

The tool’s interface consists of two simple Excel-based spreadsheets, “Concept” and “one_building_scenario”, and spreadsheets for each of the building element containing graphs with representations of their environmental impacts. In the first spreadsheet, building practitioners first define the basic parameters for hospital building geometry, such as the number of beds, the square metres per bed, and the number of floors (see Figure 4).

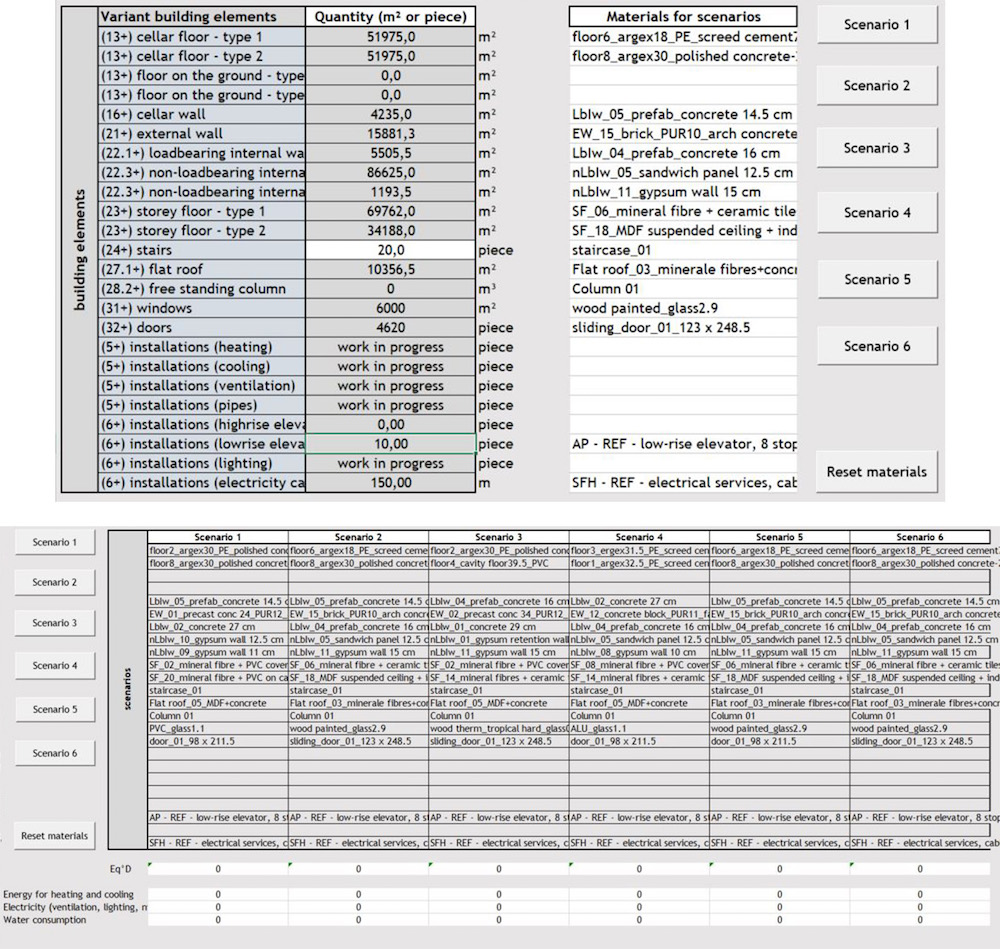

Based on these inputs, the tool already calculates the gross floor area, the area of one floor, the thermal envelope, and the building volume. Furthermore, the tool provides estimates of the building element ratios that will later serve for the calculation of the environmental impacts of the materials used for hospital construction. Building practitioners can choose predefined technical solutions for different building elements and input them for a scenario. Buttons for each scenario copy and paste the values for the energy, electricity and water consumption calculation, while ‘reset materials’ buttons clear the selections under the ‘Materials for scenarios’ if necessary. All these steps can be seen in Figure 5. Based on the choice of a predefined technical solution for floor on ground, external walls, windows and roofs, the tool will inform building practitioners whether their choices are in line with the Flemish Energy Performance of Buildings (EPB) regulation,23,24 by displaying the cells of U-values in either red (not in line with the EPB) or green (in line with the EPB) (see Figure 4). Once the U-values correspond to the EPB regulation, they help calculate the operational energy for spatial heating using the parametric design in Rhinoceros, and the Ladybug and Honeybee plug-ins.

Based on these inputs, the tool already calculates the gross floor area, the area of one floor, the thermal envelope, and the building volume. Furthermore, the tool provides estimates of the building element ratios that will later serve for the calculation of the environmental impacts of the materials used for hospital construction. Building practitioners can choose predefined technical solutions for different building elements and input them for a scenario. Buttons for each scenario copy and paste the values for the energy, electricity and water consumption calculation, while ‘reset materials’ buttons clear the selections under the ‘Materials for scenarios’ if necessary. All these steps can be seen in Figure 5. Based on the choice of a predefined technical solution for floor on ground, external walls, windows and roofs, the tool will inform building practitioners whether their choices are in line with the Flemish Energy Performance of Buildings (EPB) regulation,23,24 by displaying the cells of U-values in either red (not in line with the EPB) or green (in line with the EPB) (see Figure 4). Once the U-values correspond to the EPB regulation, they help calculate the operational energy for spatial heating using the parametric design in Rhinoceros, and the Ladybug and Honeybee plug-ins.

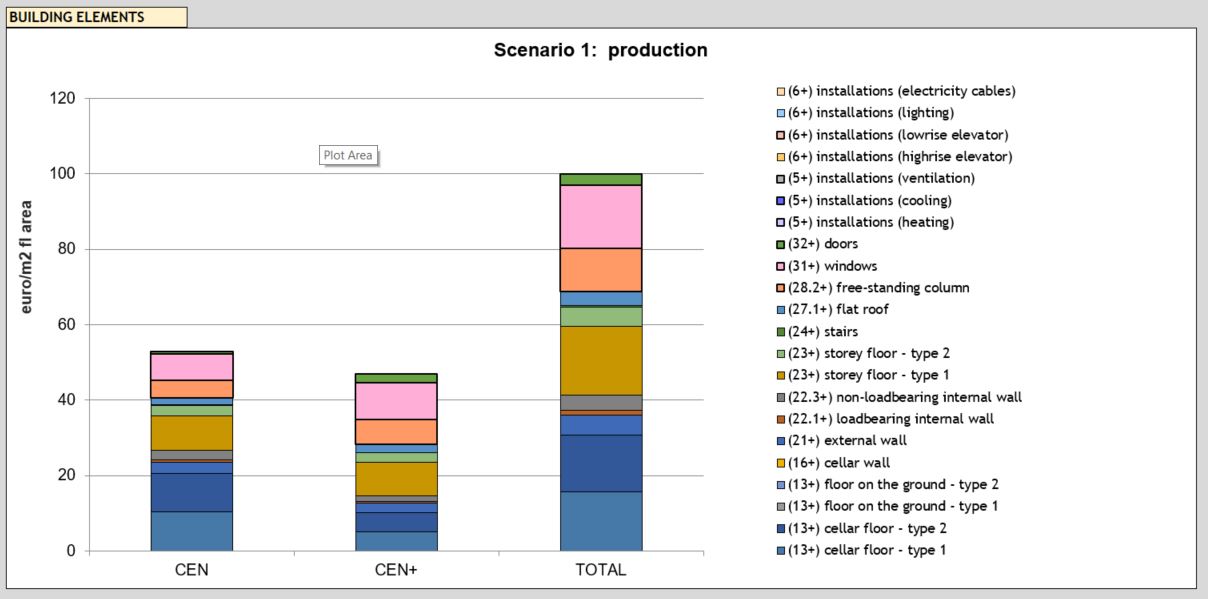

The second dashboard, “one_building_scenario”, allows for a more detailed report of a specific building scenario, including an overview of building element ratios and choices of construction materials. Building practitioners can select which lifecycle stage they would like to see the impacts coming from building elements (see Figure 5). There are also options to select the graph presentations based on the monetary impacts or impact equivalent. The results of these selections refer to the spreadsheets for building elements, with graphs representing the comparison of their environmental impacts and financial costs. These last spreadsheets serve as information on the most optimal solution of each building element in terms of their environmental performance.

Energy and electricity calculation

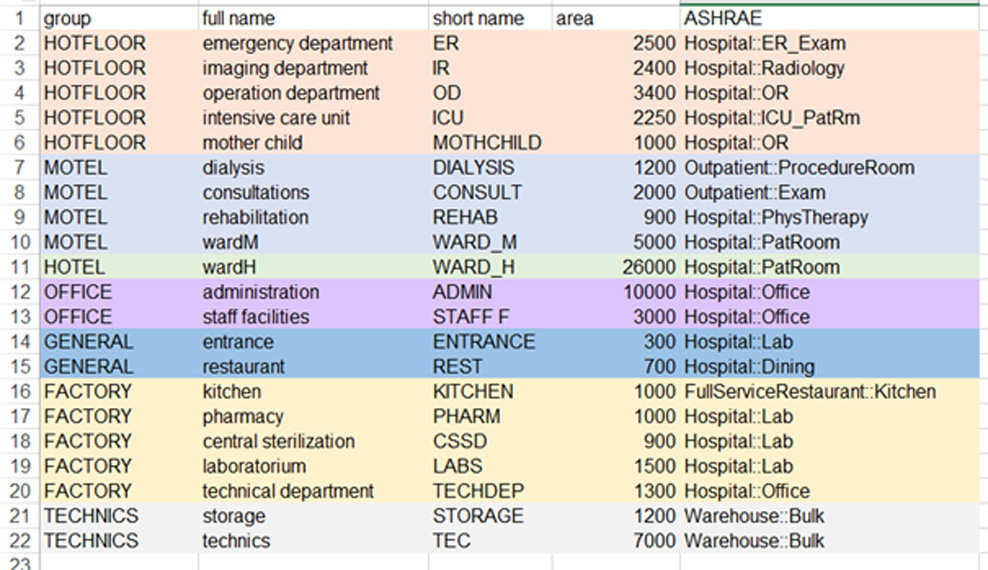

To build up the 3D model of a hospital building, Grasshopper needs an Excel table with different hospital departments, the desired area according to the competition programme, and the correlating zone programme for the energy calculation (see Figure 6). For the purpose of this research paper and to define the zones in a hospital building, we used ASHRAE Standard 55, already available in the Ladybug plug-in.25 Grasshopper makes Rhinoceros layers for each department based on group name, layout and grid for each level of the hospital. The building practitioner defines the structural grid of a building and the model of the building (based on Prasad).22

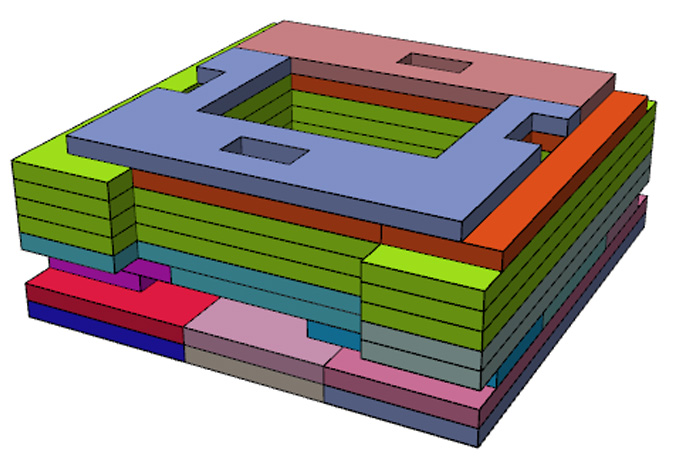

All areas are extruded with 4.1m to brepsiii and placed on top of each other, as shown in Figure 7. This will serve as the input for the energy calculation. Ladybug converts these into zones, relying on the zone programme defined in the Excel table. A window opening percentage is then defined with the Honeybee window creator using the scripting language (see Figure 8). An EnergyPlus construction is assigned to the windows, external walls, walls to the ground, the ground floors, and the roofs.

All areas are extruded with 4.1m to brepsiii and placed on top of each other, as shown in Figure 7. This will serve as the input for the energy calculation. Ladybug converts these into zones, relying on the zone programme defined in the Excel table. A window opening percentage is then defined with the Honeybee window creator using the scripting language (see Figure 8). An EnergyPlus construction is assigned to the windows, external walls, walls to the ground, the ground floors, and the roofs.

Results

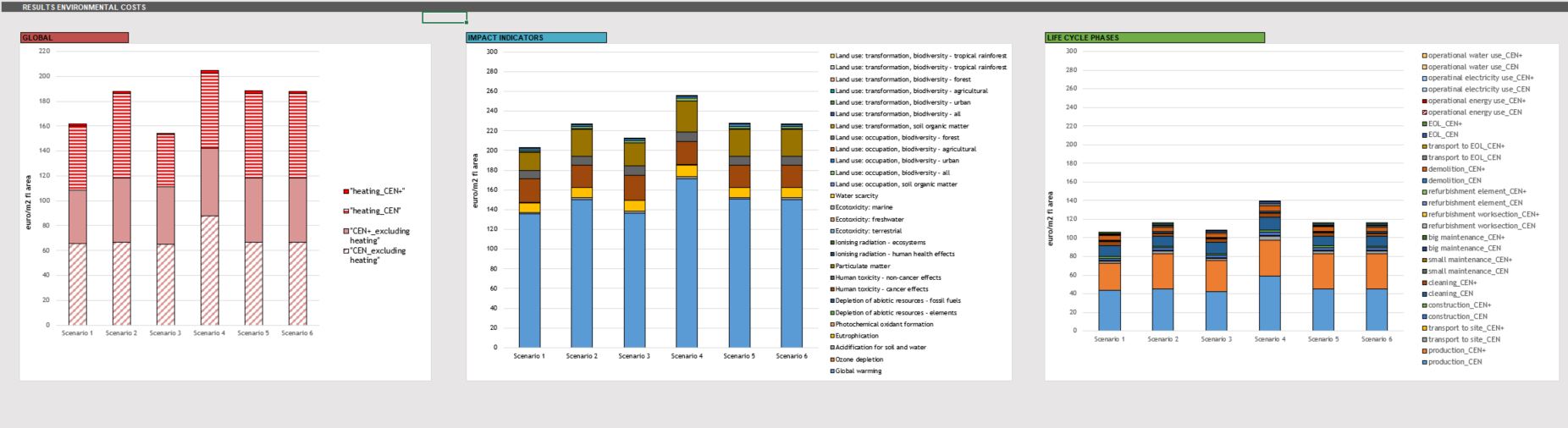

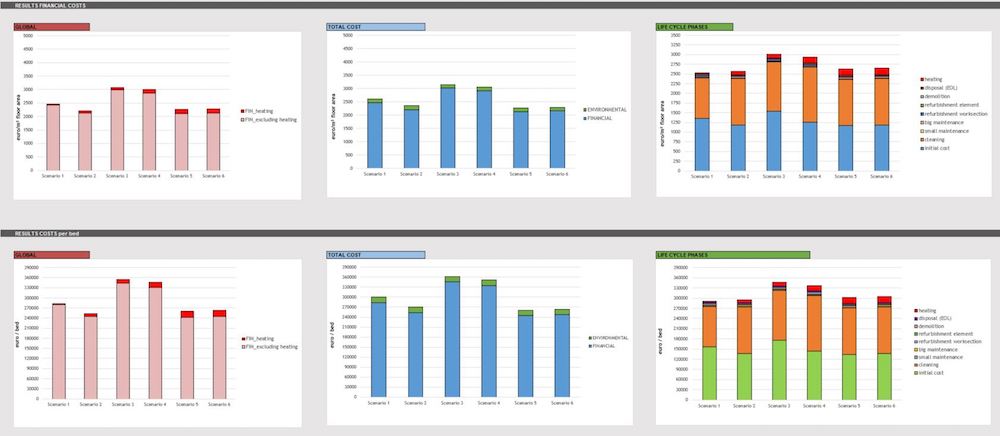

The results of the calculations are presented on the graphs in the “Concept” spreadsheet. Using the monetary values to express the external lifecycle costs explained above, it’s possible to simultaneously track and control both the environmental and financial costs of a hospital building. The presentation of the results is split into three sections: results of environmental costs; results of financial costs; and results of the financial costs per hospital bed, respectively.

In the first section, the results of the environmental costs are subdivided into three graphs representing the six hospital building scenarios in global environmental cost, results per impact indicators, and results per lifecycle stages (see Figure 9). Similarly, the results for financial costs are represented with the difference of a graph showing the total cost per building scenario, coupling the environmental and financial cost together (see Figure 10).

The results for a chosen building scenario on the “one_building_scenario” dashboard are again given per global environmental impacts, including the impacts from the spatial heating per impact indicators and per lifecycle stage. An additional graph is provided to visualise the impacts per building element for a chosen lifecycle phase (see Figure 11).

Conclusions

In this paper, a tool for evaluating the sustainability of hospital buildings during the early-design phase, and based on lifecycle thinking, is described. The advantage of this tool lies in its ability to provide estimations of the environmental and financial costs based on the few design parameters necessary to define the building geometry. The tool allows for a comparison of six scenarios to optimise the hospital building in relation to both the environmental and financial costs, as well as its overall energy consumption. By combining the tool with the Rhinoceros programme and its plug-ins, Ladybug and Honeybee, the developed method can be applied in other climatic contexts. Furthermore, the combination of lifecycle assessment (LCA) and lifecycle costing (LCC) with the energy calculations provides a powerful tool to optimise a hospital building from an early-design stage. The tool is also applicable to other healthcare facilities of a smaller scale.

The next steps include developing the calculation of the electricity consumption for ventilation, cooling, lighting and medical apparatus. Moreover, the energy calculation for spatial heating should be refined using the EPB norms for Flanders, integrated in the tool. The database of HVAC installations will also be expanded to provide a complete insight into the environmental impacts and financial costs of hospital buildings. Validation of the tool will be conducted throughout its use by VK Architects & Engineers in future competitions.

Authors

Milena Stevanovic is a project architect at VK Studio Architects, Planners & Designers, as well as a PhD candidate at KU Leuven. Co-authors Rense Vandewalle and Stéphane Vermeulen also work at VK, while Karen Allacker is an assistant professor at KU Leuven.

References

- Stevanovic, M, Allacker, K, Vermeulen, S. Evaluating the hospital building sustainability: Applying a screening LCA and LCC to the new general hospital in Mechelen. In: PLEA Conference Proceedings: Design to Thrive. 2017.

- Aspinal, S, Sertyesilisik, B, Sourani, A, and Tunstall, A. How accurately does Breeam measure sustainability? Creat Educ [Internet]. 2012; 03(07):1–8.

- ISO 14040. Environmental Management – Life Cycle Assessment – Principles and Framework. Vol. 3. 2006; p20.

- Allacker, K, Debacker, W, Delem, L, De Nocker, L, De Troyer, F, Janssen, A et al. Environmental profile of building elements (MMG report). Towards an integrated environmental assessment of the use of materials in buildings. [Internet]. Mechelen. 2013.

- CEN editor. Sustainability of construction works. Assessment of environmental performance of buildings. Calculation method. 2011.

- European Commission – Joint Research Centre – Institute for Environment and Sustainability. General guide for life cycle assessment – Detailed guidance [Internet]. International Reference Life Cycle Data System (ILCD) Handbook. 2010; 398 p.

- Trigaux, D, Wijnants, L, De Troyer, F, and Allacker, K. Life cycle assessment and life cycle costing of road infrastructure in residential neighbourhoods. Int J Life Cycle Assess [Internet]. 2016; 1–14.

- Trigaux D, Allacker K, and De Troyer, F. Model for the environmental impact assessment of neighbourhoods. In: Environmental Impact II. Southampton: WITpress. 2014; p. 103–14.

- CEN editor. EN 15643-4:2012 – Sustainability of construction works – Assessment of buildings – Part 4: Framework for the assessment of economic performance [Internet]. 2012 [cited 17 Apr 2018].

- Aspen (Ed). ASPEN INDEX-Nieuwbouw (translated title: ASPENINDEX-New construction), Antwerpen. 2015.

- Aspen (Ed). ASPEN INDEX-Ombouw (translated title: ASPEN INDEX-Renovation), Antwerpen. 2015.

- Lin, B, Yu, Q, Li, Z, and Zhou, X. Research on parametric design method for energy efficiency of green building in architectural scheme phase. Front Archit Res. 2013; 2(1): 11–22.

- EPBD recast. Directive 2010/31/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 May 2010 on the energy performance of buildings (recast). Off J Eur Union. 2010; 13–35.

- Shikder, S, Mourshed, M, and Price, A. Optimisation of a daylight window: hospital patient room as a test case. Proc Int Conf Comput Civ Build Eng. 2010; (2003): 8.

- Sherif, A, Sabry, H, Wagdy, A, and Arafa, R. Daylighting in hospital patient rooms: parametric workflow and genetic algorithms for an optimum façade design. The American University in Cairo (AUC), Cairo, Egypt Faculty of Engineering, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. Build Simul Conf. 2015; 1383–8.

- Flemish Government. Besluit van de Vlaamse Regering houdende de procedureregels voor de subsidiëring van infrastructuur van ziekenhuizen [Internet]. 2006 [cited 23 Apr 2018].

- VIPA. Maximaal toelaatbare U-waarden [Internet]. 2017 [cited 23 Apr 2018]. Available from: http://www2.vlaanderen.be/economie/energiesparen/epb/doc/epbuwaarden2017.pdf

- NHS Estates. Ward layouts with single rooms and space for flexibility [Internet]. TSO (The Stationery Office). 2005.

- Abid, A, and Alghazawi, O. The ideal structural system in hospital buildings [cited 23 Apr 2018].

- 2014 WS. The Planning Grid: Creating a Framework for Design. 2014.

- Roudsari, MS, Pak, M, and Smith, A. Ladybug: a parametric environmental plug-in for Grasshopper to help designers create an environmentally conscious design. In: 13th Conference of International building Performance Simulation Association. 2013; p. 3129–35.

- Prasad, S. Changing Hospital Architecture. London, United Kingdom: RIBA Publications. 2008; 288 p.

- Flemish Government. Besluit van de Vlaamse Regering van 11 maart 2005 tot vaststelling van de eisen op het vlak van de energieprestaties en het binneklimaat van gebouwen; 2005.

- EPB. U-waarden vanaf 2017. 2017.

- ASHRAE. Standard 55 – Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. 2013.

Further information

i Accredited beds – number of beds assigned for each hospital function (geriatrics, ICU, maternity, etc) by the Belgian government, based on which hospitals receive subsidies.

ii Eng. Flemish Institute for Person-related Matters

iii Brep – short for boundary representation, a terminology Grasshopper3D uses for a composition consisting of multiple surfaces.

Organisations involved