Healthcare / Climate adaptation

The world’s most climate-smart hospital

By Per Olsson, Gabrielle Bergh, Eirik Wærner and Mikael Pontoppidan | 17 Sep 2022 | 0

Per Olsson, Gabrielle Bergh, Eirik Rudi Wærner and Mikael Pontoppidan consider the risks and benefits of climate-smart solutions in respect of several design and engineering aspects and illustrate how existing climate-smart solutions can work in a hospital environment to lower carbon dioxide emissions, cost, and risk perspectives regarding patients’ health and wellbeing.

Authors of scientific paper:

Abstract

The buildings and construction sector accounted for 36 per cent of final energy use and 39 per cent of energy and process-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 2018 – 11 per cent of which resulted from manufacturing building materials and products such as steel, cement, and glass. To fulfil the ambitions of the Paris agreement, we must reduce our climate impact by more than 50 per cent over the next eight years.

In the world of hospital design and construction, there is a lot of talk of sustainability, but few projects are executed to a satisfactory level of environmental impact – with excuses about prioritising clinical and operational requirements. But the climate challenge does not leave space for excuses. According to Health Care Without Harm, if the health sector were a country, it would be the fifth-largest emitter on the planet. Therefore, the sector must respond to the climate emergency not only by treating those made ill, injured, and dying from the climate crisis and its causes, but also by practising primary prevention by radically reducing its own emissions. If we do not act, we have a planetary catastrophe and a huge cost waiting. A temperature rise of 2oC is estimated to cost €120bn/year compared with today’s €11.5bn/year.

Objectives and outcomes: Healthcare design is of vital importance to society, and perhaps that is why the political and day-to-day practical priorities take over. We can’t wait any longer, however. The climate question must become an integral part of healthcare projects. We need to listen to science and start focusing on climate-smart healing architecture. In this paper, we want to mobilise the necessary skills in healthcare design and thereby pave the way towards the world’s most climate-smart hospital. We know what technical solutions work, when the target is to significantly lower the carbon footprint of buildings. To reach this goal, the climate question must be part of the equation from an early stage of a project. As architects and engineers, our extensive experience from climate-smart design in other building typologies, has shown us that is possible. We have collected and tested solutions that work from cost, production and patient security perspectives and put together a virtual project that will reach a net-zero carbon emissions over the life cycle of the building. In this paper, we will present both risks and benefits of climate-smart solutions in relation to: foundations; load-bearing structures; the building envelope; interior walls and surfaces, which represent the largest proportion of upfront carbon. Other factors such as heat-loss form factor (HLFF), ventilation, energy systems and optimised solar energy production present a significant reduction potential looking at the total carbon emissions; however, this paper chooses to focus on upfront carbon.

We will demonstrate solutions and how they work in a hospital environment to lower carbon emissions, cost impact, and risk perspectives regarding patients’ health and wellbeing. There are competing definitions for net-zero buildings, but to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, we must focus on both ‘upfront carbon’ embodied in construction materials as well as significantly lowering the carbon footprint of buildings through their life cycle.

Keywords

When talking about sustainability, there is a tendency that we focus on long-term effects and lifecycle perspectives – and less about the carbon footprint generated here and now by the construction of new buildings. But the Paris agreement’s long-term ambitions cannot stand alone, and we must focus on the short-term actions to lower upfront emissions, in addition to the long-term operational emissions.

To reach the Paris Agreement’s 1.5oC target, the global climate goals for 2050 also demand several short-term achievements. Within the next three years, the increase of carbon emissions must stop, and by 2030 the global industry’s annual emissions must be halved, according to the latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)1. As the World Green Building Council states, we must cut upfront carbon emissions within the construction industry by 40 per cent before 2030.

The window of opportunity is now

The two most central messages of the IPCC report are urgency and opportunity. Urgency regarding what we must do to change. But in the current transition, there are also opportunities that lie ahead, with the IPCC stressing that the next few years are critical. Technologies are readily available to halve global emissions by 2030. The carbon emissions quota is not an abstract matter; once the quota has been used up, it will be extremely difficult and costly to reverse, and many damages will be permanent. Therefore, urgency and short-term focus is essential.

Focus on upfront carbon – a must for new construction

This article will focus on upfront carbon emissions (emissions associated with materials and construction processes), as these are the most important tools for us, as architects and engineers, to make the necessary impact now. In addition, we will show that existing solutions can halve hospital upfront emissions.

The buildings and construction sector accounted for 39 per cent of global carbon (CO2) emissions in 2018. Of this total, 28 per cent relate to buildings operations and energy use. But 11 per cent of global emissions relate purely to materials used for construction – and a large part is consumed in the construction of new buildings2.

A report from the World Green Building Council states: “Carbon emissions released before the building or infrastructure begins to be used, sometimes called upfront carbon, will be responsible for half of the entire carbon footprint of new construction between now and 2050, threatening to consume a large part of our remaining carbon budget2.”

This shows us that by lowering upfront carbon emissions when building new hospitals, we can make a massive difference in the short term. This presents a major opportunity and responsibility on us when we design and construct hospitals. It does not mean that we stop focusing on life-cycle carbon emissions, but it should make us aware of the need to focus on upfront carbon emissions. In short, decarbonising our sector is the most cost-effective way to achieve our climate goals.

Hospitals have much to gain from a transition

In the United Kingdom alone, 48 new hospitals are planned by 2030. As the world’s population approaches 10 billion, this trend in infrastructure will be universal. Therefore, there is a need to develop practical concepts and solutions specifically in hospital projects, owing to their specific conditions and requirements. From a Nordic perspective, an energy focus has been predominant for several years. But lately the climate urgency has forced us to increase focus on the full scope of carbon emissions. This has made know-how and technologies available to be applied within the area of climate-focused architecture.

In the world of hospital design and construction, there is much talk of sustainability, but few projects are executed to a satisfactory level of environmental impact – with excuses about prioritising clinical and operational requirements. But the climate challenge does not leave space for excuses for anyone. Business as usual is not an option. According to the organisation Health Care Without Harm, if the health sector were a country, it would be the fifth-largest emitter on the planet3. Therefore, the sector must respond to the climate emergency, not only by treating those made ill, injured, and at risk of dying owing to the climate crisis and its causes, but also by practising primary prevention by radically reducing its own emissions. If we don’t act, we have a planetary catastrophe and a huge cost waiting us. A temperature rise of 2oC is estimated to cost €120bn/year compared with today’s €11.5bn/year, for climate-related catastrophes in Europe alone4.

Stick to your budget

What do budgets have to do with climate-smart architecture? There are many similarities between the way we look at economic budgets and how we need to start thinking about carbon emissions in our construction projects. As architects and engineers, we are used to handling financial budgets and to adapt ambitions accordingly. We must start handling carbon budgets with the same dedication and respect as we do financial restraints. Therefore, we must define and stick to a carbon budget related to the global emissions quota – just as we do when dealing with financial budgets. As opposed to the local nature of project financing, the emissions quota is global and shared by all.

Emissions continue to increase despite global agreements and a growing sense of urgency. The later we manage to stop the increase, the more drastic measures will be required to succeed. On carbon emissions, it’s time that we took responsibility for our budget and stop living beyond our means.

Our carbon budget must contain both the long-term energy and the short-term, upfront carbon emissions. The two parameters together reduce a building’s climate impact over its life cycle. As operational carbon levels fall, and the energy mix becomes more renewable, embodied carbon emissions will make up a growing proportion of the industry’s total emissions.

The definition of net-zero emission buildings

How we define net-zero emission buildings has a major impact on how we will succeed in lowering emissions now. Today, upfront carbon has a secondary position in the definition, which often results in a lack of focus. Instead, compensation and other measures, which have a questionable impact on emissions, are being employed.

Where do we start?

If we are to reach the climate goal on this short-term perspective, as called for by the IPCC, we must reduce the initial impact of our hospital projects. We can do this by working with resource-efficient solutions, climate-smart materials, and climate-smart construction. We have the necessary knowledge, products, and production technology at our disposal to reduce the climate impact by half, compared with the current level.

At present, the lack of focus on upfront carbon results in higher emissions than necessary. Introducing upfront carbon emissions as a valuation factor when choosing methods and materials, can result in a drastic drop in emissions. So where do we start?

- We must understand the impact of our choices on the upfront carbon and make subsequent informed choices. All projects count – large and small alike.

- We must know where we are today, to understand the challenge that we face and the potential of reduction.

- We must relate our emissions to the remaining carbon budget, and respect it as a global quota.

- We must set trustworthy targets (level of CO2 kg/gross m2) for how much we will reduce carbon dioxide emissions in hospital projects and actively steer towards these goals.

- We must ensure that the work on the carbon budget is as integrated as the financial budget into project management.

- We must agree that climate compensation carries an internal conflict between present environmental impact and future relief and must be used with moderation.

Integrate the climate budget as project economy

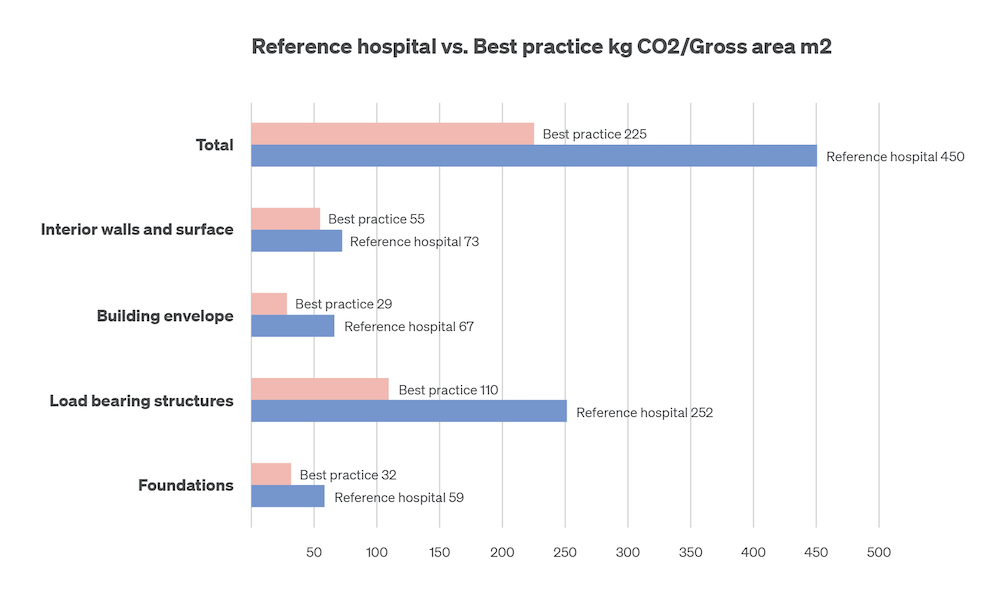

Reducing the climate impact of construction projects is not rocket science. The opportunity to significantly reduce the climate impact is already here and, as architect and engineers, we develop projects with 60 to 70 per cent lower climate impact than standard buildings. This is achieved through focusing mainly on four building parts that represent a major part of carbon emissions.

Our extensive experience of climate-smart design in other building typologies reveals what is possible. We have collected and tested solutions that work from a cost, production, operational and healthcare perspective, mainly focused on the most climate-intense parts of construction but also the ones most challenging in relation to healthcare projects. There are opportunities to deliver climate-smart solutions related to: foundations; load-bearing structures; building envelope; interior walls and surfaces; ventilation, energy systems and optimised solar energy production.

Carbon emissions must be part of the equation from an early stage of the project. This is where we, as architects and engineers, can make a real difference, in ensuring that the climate budget is as integrated as project economy. Both budgets must be considered equally.

Carbon emission limbo – how low can we go?

The need to halve carbon emissions by 2030 is possible with available know-how and technology. When comparing against a traditional hospital in Scandinavia, our tested low-emitting solutions will result in a reduction of upfront carbon emissions by 50 per cent. This is what we can deliver within the financial and practical reality of today. It’s merely a priority.

Foundations

When looking at a hospital, a large portion of emissions come from foundations. Even if our experience shows that low-emitting materials can replace concrete foundations, it cannot, at present, be applied to large-scale hospital projects. In this virtual project, we therefore use a traditional solution with a low-carbon emission concrete.

Load-bearing structures

The most common way to lower emissions in load-bearing structures has been through replacing steel and reinforced concrete with wood structures. The challenge in hospital projects, however, is the need for large spans of structures and certain operations’ sensitivity to vibrations and regulations regarding fire and noise control. Hence, there will be limitations to the total application of wood. The rest of the construction will be made up of low-carbon concrete. Using low-emitting concrete results in a good combination of architectural flexibility and lower carbon emissions but the benefits of the wood’s sequestered carbon is lost as a renewable material.

Building envelope

Another area of architectural importance is the facades and roofs that make up the building envelope. This is important owing to its impact on the surroundings, the indoor environment, energy usage for heating and cooling, etc. Therefore, the envelope must be optimised from a holistic perspective to deliver low emissions, but without losing sight of other sustainability aspects of the facade. Recycled and renewable materials are effective ways to lower the carbon emissions, but these must be applied where they work most effectively, considering sustainability, form and function.

Interior walls and surfaces

In many current low-emission projects, interior walls and surfaces are an obvious area to create impact by removing certain materials entirely. As a method to lower emissions, this is very effective, but it carries an internal challenge regarding patient safety, hygiene, fire safety, and noise regulations. Therefore, this method can be difficult to apply at a large scale. So, to lower carbon emissions of interior walls, the obvious choice is to use wood as a core material, wherever possible, replacing steel and concrete. When it comes to surfaces, the material choice is currently very limited, demanding urgent research and development of new, low-emitting materials suitable for hospital environments.

Ventilation, energy systems and optimised solar energy production

In addition to the above four building elements, installations represent a large potential. There is clear evidence that by evaluating carbon emissions when for example choosing ventilation systems, upfront emissions can vary by up to 65 per cent.

Conclusion

We live beyond our means, which makes it difficult to do the right thing. But we have the necessary tools to make a difference today, by employing the know-how and technology available. It’s not rocket science, but it requires a change of mindset and a shift in focus when we design and build the hospitals of the future. If we manage to improve today, we will increase the possibility for a better tomorrow.

The necessary green transition requires both a focus on the now and a long-term commitment to the carbon emissions budget. An overdraft comes at a massive cost, so this budget is non-negotiable.

The most environmentally friendly approach is to build nothing – or reuse existing buildings and materials. But this is not always possible, owing to growing demands caused by demography and increased living standards globally. To reach a net-zero future, innovative and circular solutions are needed, and these require a continued focus in research and development.

Reaching the first target towards the Paris agreement – 50 per cent lower emissions in hospital projects by 2030 – is possible if we work together, and it’s everyone’s responsibility, including politicians, clients, consultants, contractors, and suppliers. Hospitals are complex entities, but we must find ways both to solve clinical requirements and stick to the budget – financially and sustainably. Collaboration is the stuff of sustainable growth.

About the authors

Per Olsson M.Sc. Civ.Eng, is head of sustainability at LINK Arkitektur; Gabrielle Bergh MA Architecture is a healthcare specialist at LINK Arkitektur, and associate professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU); Eirik Wærner is an environmental advisor at Multiconsult; and Mikael Pontoppidan MA Architecture, MBA, is commercial director at LINK Arkitektur.

References

- Climate Change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. (2022). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Sixth Assessment Report. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/

- Bringing embodied carbon upfront. (2019). World Green Building Council. Available at: https://www.worldgbc.org/news-media/bringing-embodied-carbon-upfront

- Health care’s climate footprint. (2019). Health Care Without Harm (HCWH) and Arup. Climate-smart healthcare series, Green Paper Number One. Available at: https://noharm-global.org/sites/default/files/documents-files/5961/HealthCaresClimateFootprint_092319.pdf

- Climate change, impacts and vulnerability in Europe 2016: An indicator-based report. (2017). European Environment Agency. EEA Report, No 1/2017; ISSN 1977-8449. Available at: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/climate-change-impacts-and-vulnerability-2016

Organisations involved