Cancer care / Workforce

Comment

Revisiting an early exemplar of person-centred design for patients and staff

25 Jul 2023 | 0

‘Health and wellbeing’ has become something of a buzz-phrase in today’s society, with its meaning often diluted through its attribution to any number of ‘wellness’ fads. However, argues Neil Orpwood, there is a valid link between the two, which is becoming increasingly prominent in contemporary healthcare facilities, as a return visit by architects to one of their own cancer centre projects highlights.

By its very nature, the healthcare environment garners a wide variety of mixed emotional responses from its users, with patients, staff and visitors all experiencing very different stresses. Pressures on the NHS have long been documented, and the current staff shortages have only added to the strain. Hospital and community health services lost almost 170,000 staff in 2022, and, according to the Nuffield Trust, references to “work-life balance” as a reason for moving role within the health service have quadrupled in the last decade.1

It’s crucial that for those on the front line of delivering healthcare, the work environment is designed to minimise this duress, maximise wellbeing, and ultimately allow patients to receive the best experience possible.

‘Wellbeing’, although linked to the physical, is often associated with the mental and emotional state, whereas ‘health’ is more commonly attributed to the physical form. The challenge for design teams is to sensitively adapt the environment to promote wellbeing, maintain functionality for improving health, and meet hygiene standards (through early involvement of infection prevention control teams) – all while minimising negative associations.

As in many workplaces, staff wellbeing is central to the working environment and vice-versa. By placing the wellbeing of staff on the same level as patients, all building users are accommodated. After all, the patient experience is both a direct response to the environment they are in and the care they receive. And while healthcare facilities have a very clear purpose of caring for patients, it’s essential to provide nurturing environments for staff at the same time. Successful healthcare design benefits all user groups, enabling and encouraging health and wellbeing – from the everyday working experience to the most delicate, emotional, personal experience. Given recent experiences and challenges, from the pandemic to the cost-of-living crisis, it’s now more important than ever that we address the stresses in the workplace environment to ensure greater wellbeing for NHS staff and patients.

Moreover, this is not the only way in which the design of healthcare has been turned on its head in recent years. Far from the traditional, clinical and uniform approach, more thought is at last being given to how people experience their time in these facilities. Rather than a ‘production line’ mentality, in which people are chivvied through as quickly as possible, clients and designers are now recognising the true value of wellbeing and the power of a considered environment to improve the overall experience.

HLM recently revisited the Queen’s Centre for Oncology and Haematology, in Cottingham, East Riding of Yorkshire. With the building reaching its 15-year anniversary for post-handover and entering the final seven-year PFI delivery phase, we wanted to understand what had changed, what’s been reconfigured and, specifically, how well the landscape is performing in the 13 courtyards, gardens, and surrounding parkland setting – particularly in the context of the growing focus on the relationship between health and wellbeing.

When we were appointed to design the Centre, back in 2002, our team worked closely with the client to create a specific design approach that put the user experience at the forefront. Fast-forward 20 years, and the project is still regarded as an exemplar of people-centred design in healthcare.

Tranquility and psychological wellbeing

As part of an estate rationalisation plan to increase operational efficiency between departments, the new centre at Castle Hill Hospital saw the integration of radiotherapy, oncology and haematology facilities from three previous sites into one unit.

From the outset, it was established that in stark contrast to the clinical ambience of many hospitals, the new unit would imbue a sense of tranquillity and peace of mind. Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust’s vision was that the completed unit would be “a healing environment” and as unlike the typical clinical atmosphere of most hospital buildings as possible. This provided an exciting element to the challenge of co-locating these important departments in a catchment area of more than 1.2 million people.

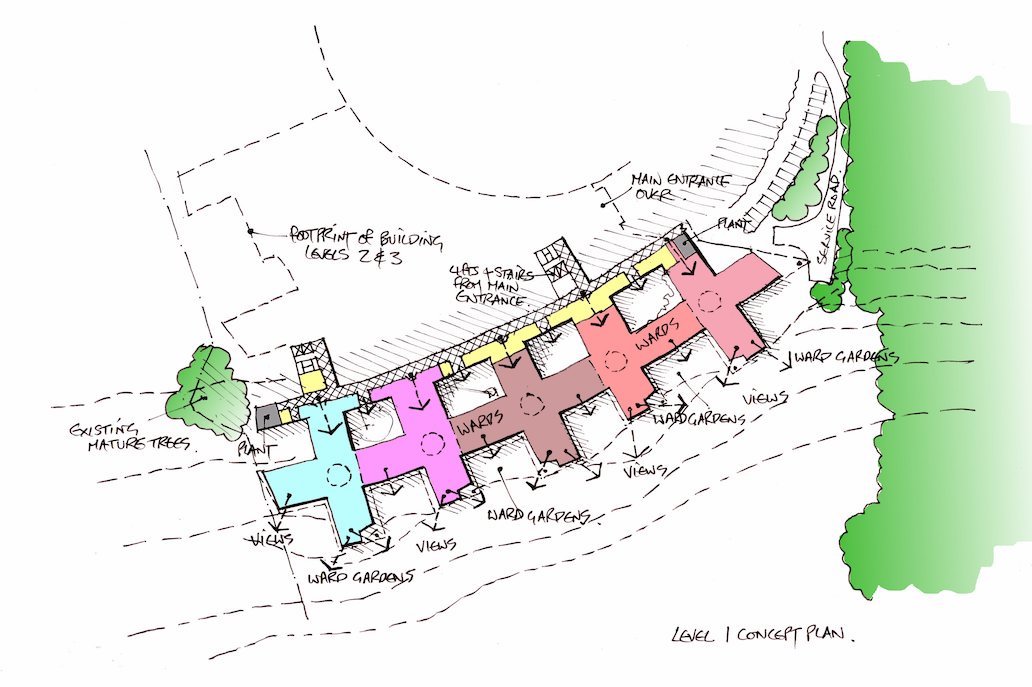

The sloping landscaped site provides a stunning backdrop and permits extensive views for occupiers of the unit, with the natural surroundings bringing an innate sense of rest and relaxation to the facility. The mature woodland and open rural views were maximised using the site gradient to form a series of stepped terraces, linked to treatment areas. The site’s remote setting separates from the more intense nature of the existing hospital, helping to create a sense of arrival through the wooded copse, resulting in a sensitive building in a sensitive setting.

Taking inspiration from the environment

Focusing on this location’s natural beauty, the team developed a design that maximised user connection with their surroundings. Almost every one of the 800 rooms looks out over courtyards, gardens or landscape, and benefits from carefully controlled maximum daylight. Glazed links form connections between the wings, again optimising daylight and countryside/courtyard views.

Nine patient courtyards featuring intimate walled gardens and subtle landscaping optimise the psychological and physical health benefits of the countryside surroundings. Fully accessible, these pockets of sanctuary provide an area of rest and relaxation for staff, and quiet contemplation and respite for patients. A winding path links the ward gardens to each other and the wider landscape, which is shared with the community as a parkland setting. This not only integrates the unit fully with its surroundings but also provides a scenic and contemplative walk of the grounds.

The massing of the building cleverly reconciles the scale of the accommodation and the need to break this down into intimate spaces, by stepping this down along the gradient of the site. This culminates in fingers of accommodation with domestic proportions that make a prolonged stay feel more like a home-from-home with a garden setting.

Functional yet beautiful

Inspired by the location, the design team’s theme for the unit was based on an East Riding village. Its implementation fully supported the Trust’s vision to create a soothing environment, rich with personality, and contextually relevant to visiting patients.

Careful detailing was developed through consultation with 19 different user groups – such was the scale of the new unit. Material choices replicate the welcoming feel of a village vernacular, with brick, render, glass, timber, stone-coloured block-work, and small roof tiles combining to create a residential impression, minimising the clinical atmosphere for patients, staff and visitors.

Crucially, the functionality of the hospital is enhanced. Wayfinding is simple and intuitive, while colour and artwork has enhanced navigation. The unit has specific clinical functions, but the internal structure provides flexibility through adaptable building systems and flexible layouts. All these design decisions were carefully developed to ensure the person is at the centre of healthcare; the experience of each user group – be it patients, staff, or visitors – is improved through reimagining what was (and often still is) the ‘typical’ hospital environment.

Crucially, the functionality of the hospital is enhanced. Wayfinding is simple and intuitive, while colour and artwork has enhanced navigation. The unit has specific clinical functions, but the internal structure provides flexibility through adaptable building systems and flexible layouts. All these design decisions were carefully developed to ensure the person is at the centre of healthcare; the experience of each user group – be it patients, staff, or visitors – is improved through reimagining what was (and often still is) the ‘typical’ hospital environment.

Some 15 years on from handover, and the design is still praised for advancing what is now a widely recognised design approach to hospital environments – building healthcare that supports relationships; providing working environments that encourage wellbeing as well as healing; and designing for staff to ensure they can provide the best patient experience.

Flexibility and adaptability

When revisiting the centre, the ability of the building to flex – particularly one that is 20,000m² in size – was very evident. Since completion, the building has allowed services to grow and adapt over time, owing to flexible ward layouts and adaptable clinical and breakout spaces.

The need for a new Acute Assessment Unit, particularly during the pandemic, was recognised and has been successfully incorporated into a reconfigured outpatient space. This relieves pressure throughout the rest of the unit, gives staff more space than their previous arrangement, and helps ease the pressures of their day-to-day tasks. The facilities manager commented: “The pandemic did throw up a few alterations to the way the building was operated, and it held up with limited disruption to patients and staff.”

Designing for flexibility in a world of change is both an opportunity and a challenge. As designers, we must ensure that we’re capable of accommodating changes to services and healthcare provision, where helping to ease staff pressure is just as important as providing rest space.

The building provides reassurance for an area of treatment that is often fraught with uncertainty, and it has a reputation within the local community as providing high-level care in a beautiful setting. With the building having received a RIBA Gold Medal in its first year of operation, we hope that were the judges to revisit today, they would reflect our sentiments that this project has stood the test of time.

The NHS Workforce Strategy, published in June, recognises the change of culture required within the overall health service, and it outlines £2.4bn funding over the next five years to address working conditions as well as training requirements2. In this context alone, infrastructure that integrates the principles of health and wellbeing from the outset can only be an asset to the future resilience and sustainability of the health service.

It was incredibly satisfying to witness both the staff and the local community’s appreciation during our visit; users’ enjoyment of the links to the outside, both through the windows and through ease of physical access, was referenced. We believe the design was ahead of its time, and to see its relevance reflected in contemporary healthcare design themes and policy gives added fulfilment.

About the author

Neil Orpwood is associate director – healthcare at HLM Architects. He was the project lead for the original design of Queen’s Centre for Oncology and Haematology.

References

1 Ungoed-Thomas, J. ‘Revealed: Record 170,000 staff leave NHS in England as stress and workload take toll’, The Guardian, July 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jul/01/revealed-record-170000-staff-leave-nhs-in-england-as-stress-and-workload-take-toll

2 Campbell, D. ‘Government aims to boost NHS with thousands more doctors and nurses’, The Guardian, June 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jun/29/government-aims-to-boost-nhs-with-thousands-more-doctors-and-nurses

Organisations involved