Office & workplace / Healthy Cities

Mapping flexibility – a re-invented working culture

By Nuria Benítez Gómez, Rime Cherai and Jonathan Gayomali | 15 Feb 2021 | 0

This paper describes findings, reflections and insights from a workshop aimed at understanding the transition of flexibility within work and other facets of everyday life, and to reframe the desired flexibility for the future of workspace.

Authors of scientific paper:

Abstract

In the current pandemic, many people are struggling in their careers. With many of the current workforce either on furlough or working from home, how does this change the working culture post Covid-19? Will most people work one, three, or seven days from home? Only time will tell. Either way, there is no denying that the future workplace will be more based in the domestic setting, facilitated in cyberspace and digital platforms.

Designing the future workplace will consist more of not designing for the place, but for a series of disbursed places and practices. The office, the patio, the park, the coffee shop, even the beach perhaps. Currently, this balance is only speculative. Through co-creation and collaborative mapping, identifying desirable areas of social concentration and relief can allow us to design the future workplace for a dislocated urban mindset, and simultaneously help us preserve a healthy work-life balance.

Keywords

The workshop was composed of seven participants, some of whom were part of a panel and some of whom participated separately. The goal was to understand the ideal work relationship in location, time and activity, especially in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. In order to do this, we put together a series of mapping exercises for participants to help lead the conversation and discussion, while keeping a visual record of their participation.

We had earlier participated in a separate workshop, ‘WorkHomes: integrated healthy neighbourhoods built on micro businesses’, in which we took part in some role-playing that led to a discussion of how interconnected our roles are in society. This offered a good segue into our workshop.

Background

With a large percentage of the current workforce either on furlough or working from home, how does this change affect the working culture post Covid-19? There is no denying that the future workplace will be more based in the domestic setting, facilitated in cyberspace and digital platforms. Rather than focusing on a single place, designing the future workplace may consist more of designing for a series of disbursed places and practices. The office, the patio, the park, the coffee shop, even the beach can become part of the future workplace.

Currently, redefining an equilibrium is only speculative. Through co-creation and collaborative mapping, identifying desirable areas of social concentration and relief can allow us to design the future workplace for a dislocated urban mindset, and simultaneously help us preserve a healthy work-life balance. How can we use the struggles of the past few months as a driver for shaping the future of work and work culture? We chose to dissect work culture into ‘location’, ‘time’ and ‘activities’.

Methods

The seven participants were each presented with their own worksheet via Google Sheets, along with the workshop framework. This consisted of a matrix of location, time and activity laid over the course of their pre-pandemic life, current life, and post-pandemic life. The workshop was to be used as an opportunity to realise what is important to a collection of individuals and how this triad of time in the context of Covid-19 has changed their relation to work and everyday life.

For pre-pandemic life, the participants were presented with a brief survey to assess their lives in regard to work-life culture during the pandemic and raise awareness into how certain dynamics had quickly altered it. This time period was presented in a different format, owing to workshop time constraints, as we looked to place emphasis on the future. Questions were asked on understanding simple concepts such as “was the nature of your workday fixed or flexible?” or rating how productive participants’ workday was on a scale of 1-10.

A discussion led to a conceptual freefall of words. For Part I, the participants were asked to write a list of five things each that correspond to their current work life of being productive, creative, collaborative, happy, and focused; things that are important for their ordinary workspace and work environment. This resulted in a total of 25 words or phrases. The participants were then asked to narrow down this list to five words, with the purpose of selective focus. With each participant having a unique list of words, the next step was to map these onto a curated framework in order to understand these concepts in relation to time.

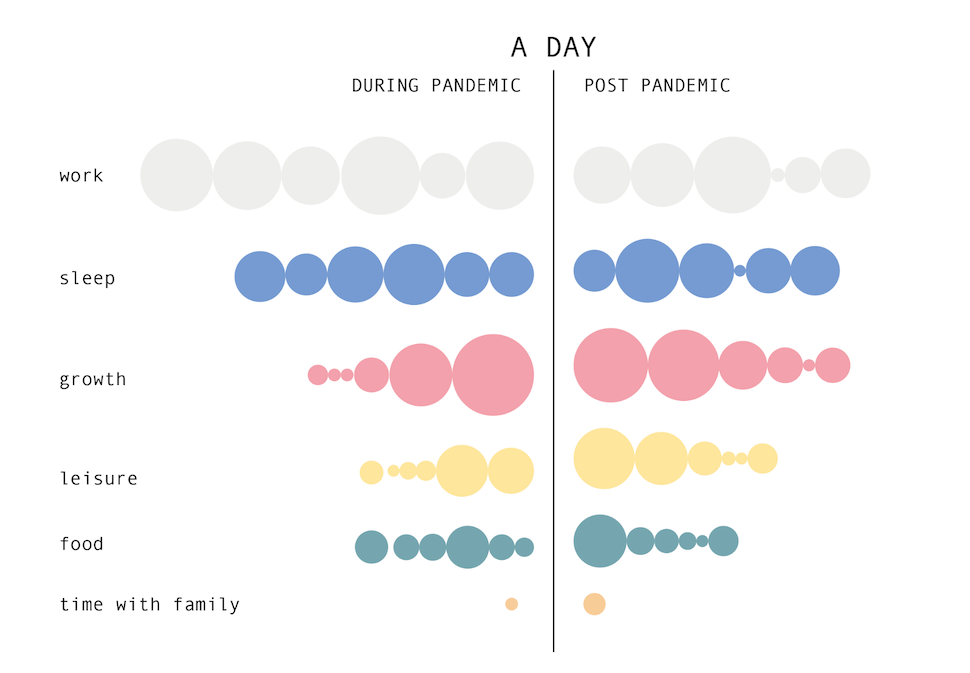

Before jumping to the second phase of the mapping process, participants were asked to move to Part II: a separate mapping exercise in which they were asked to size circles representing work, sleep, leisure, other, and growth. The purpose of this exercise was to place the basic categories of time according to personal importance.

In a shifting of focus, participants were then asked to think about their ideal work life. Looking into the future, we asked “how would you remap your post-pandemic daily schedule?” With participants having now thought about what was most important to them, this exercise was used to compare their current lives with their past lives. The aim was to strive for something that works with a condition that resembles something closer to pre-pandemic parameters, barring the restrictions presented by the current pandemic.

Throughout the workshop we encouraged the participants to interact and challenge their self-perception of work culture through playfulness as a method. Particularly during Part II’s mapping process, the aim was to trigger conversation based on an insightful activity combined with inspiration and spontaneity.

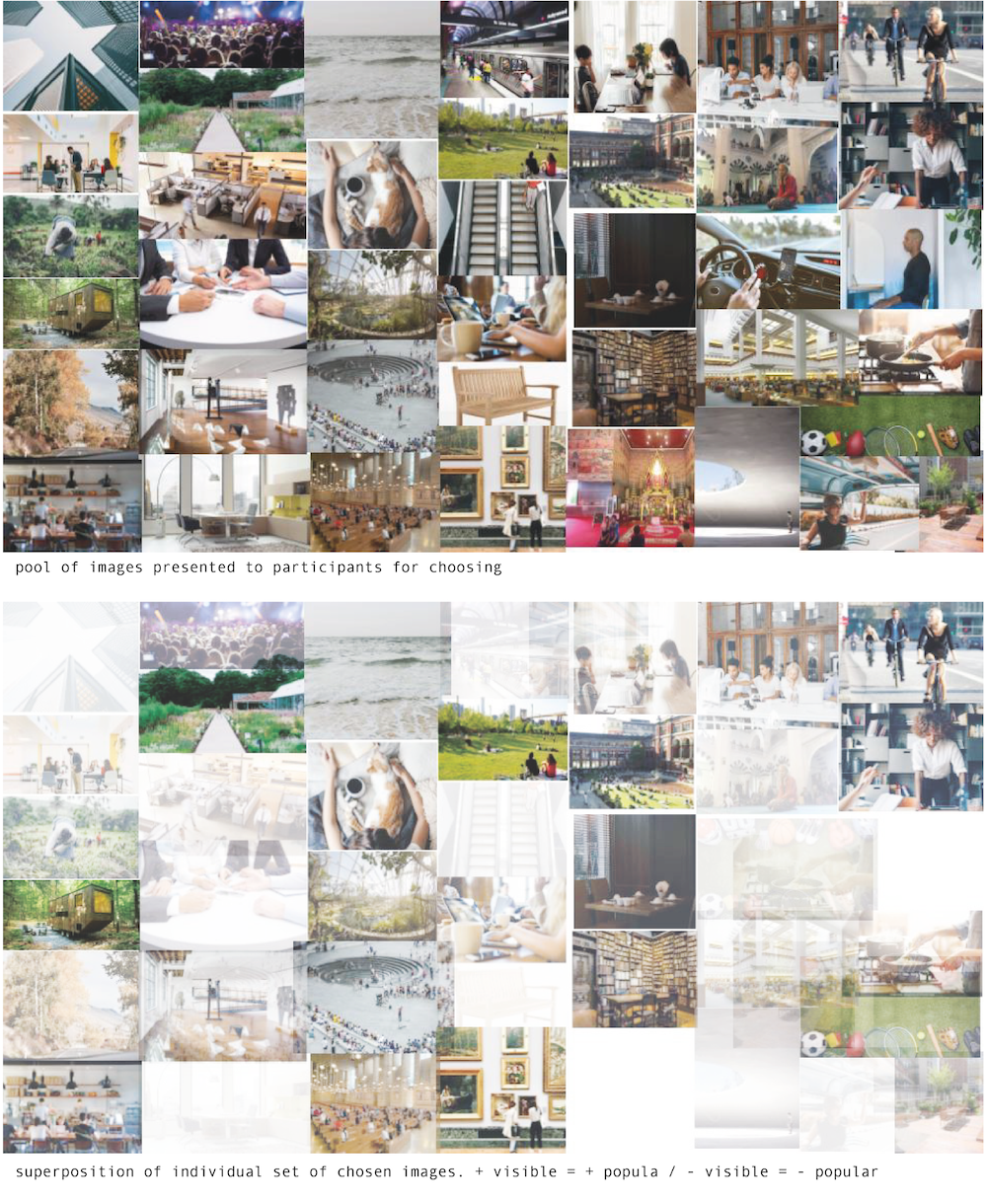

Lastly, in Part III, the concepts were applied to the idea of location within the city. The types of places that all cities have in common – such as the coffee shop, home, a bench, the commute – were presented to participants via an interactive image board. They were then asked to delete the images of least importance to them in regard to their chosen five concepts. The purpose of this exercise was to make the connection to the built environment, digital infrastructure, social life, and so forth.

Results

Part I: Results

In an attempt to rationalise the words of the conceptual freefall, the words chosen were organised by the nature of their humanistic relationship.

Related words are unique in colour:

Technology-based

Organisation-based

Environment-based

Physical-based

Knowledge-based

Feeling-based / mindset-based

Social-based

Time-based

Initial words of ‘productive’ included: wifi, software, IT support, meetings, structure, environment (wood workspace), daylight, management, chair, desk, control of tools as a team, focus, time, technology, information, research, time, clarity (clear tasks), organisation (organised diary), autonomy, flexibility, to-do list, desk, pressure, wifi connection, calm, environment, a peaceful mind, goal, clarity, focused, healthy

Feeling-based / mindset-based: 7

Knowledge-based: 5

Technology-based: 5

Environment-based: 3

Organisation-based: 3

Physical-based: 3

Social-based: 3

Time-based: 3

Total: 32

In the case of ‘productive’, it can also be assumed that there are many overlaps between concepts. For example, the concept of the to-do list can fit into the categories of ‘organisation’ or ‘time’, and the concept of control of tools as a team can fit into the categories of both ‘communication’ and ‘technology’. It was also interesting to see the categories play out, as well as the themes that many people chose. One participant, for example, focused mostly on the software, while another focused mostly on feelings. The words chosen can also be attributed to the participants’ concept of what it is to be productive as well as answering the initial question. Overall, ‘feeling-based / mindset-based’ words were most popular, and four were tied for the least popular – ‘organisation-’, ‘physical-’, ‘social-’, and ‘time-based’.

Initial concepts of ‘creative’ included: Good resources to refer to, talks to stimulate design ideas, webinars or skill-growing classes, larger space/studio, freedom and flexibility at work, printer-scanner-tools, opportunity to meet other creatives, space, time, analogue, drawing, nature, good music, interesting projects, stimulating conversation, nature, books, access to info, pen and paper, music, privacy, having ideas, a bit of deadline stress, trusted to do what I want, paper and pen on the desk.

Feeling-based/ mindset-based: 7

Knowledge-based: 5

Environment-based: 4

Physical-based: 4

Social-based: 3

Technology-based: 1

Time-based: 1

Organisation-based: 0

Total: 25

Moving to the next section, being ‘creative’ happened to have more range in words than being ‘productive’. Some categories used in the ‘production’ section were scarcely used or not used at all, such as ‘organisation-’, ‘technology-’, or ‘time-based’. Some repeating concepts were space, nature, pen and paper, and music. In order to be creative, the participants ended up choosing words that can be accomplished in many different ways. Once again, feeling-based / mindset-based words were the most popular category with a total of eight. ‘Technology’ showed a large shift compared with ‘productivity’ and only comprised one word. There were no ‘organisation-based’ words in this category.

Initial concepts of ‘focus’ included: Good podcast to listen to with monotonous work, clean environment, bright light, quietness, decent technology, a set of rituals, a separation between work and private life, air, time, privacy, space, natural light, no interruptions, music without lyrics, a cup of tea, my lap blanket, the right lighting, quietness, order, set tasks/time for work, take breaks, good workspace, workflow, silence, good wifi, updated of my family’s health, no phone, no slack, no chat, having a goal.

Environment-based: 11

Feeling-based/ mindset-based: 9

Organisation-based: 3

Time-based: 3

Physical-based: 2

Technology-based: 2

Knowledge-based: 0

Social-based: 0

Total: 30

The initial concepts of ‘focus’ consist of many themes of the environment. Out of a total of 30 concepts, 11 of them are found in the environment category – the highest number so far, and the first to overtake the number of ‘feeling-based / mindset-based’ words, which still came in near the top at nine. ‘Knowledge-’ and ‘social-based’ words both scored none.

Initial concepts of ‘happiness’ included: Daylight, routine, structure, collaboration, communication, healthy work-life balance, space to grow plants, space to make things, work hours flexibility, no commuting, walks, outside, moments, connection, friends/ family/ love, having friends at work, social connection, feeling valued, sunlight and nature, music, nice food throughout the day, coffee, tea, a bit of sugar, nice people, good coffee, morning walk in the park, a bigger monitor, a comfy chair and desk.

Physical-based: 8

Social-based: 6

Environment-based: 6

Feeling-based/ mindset-based: 4

Organisation-based: 2

Time-based: 2

Technology-based: 0

Knowledge-based: 0

Total: 28

Surprisingly, many of the factors chosen for ‘happiness’ were of a ‘physical’ nature. Food and drink, and furniture seemed to be addressed by many of the participants. Out of a total of 28, eight were of a ‘physical’ nature. Unsurprisingly, given that loneliness has proven to be one of the biggest hurdles during the pandemic, ‘social-based’ words came in second highest. ‘Technology-’ and ‘knowledge-based’ elements were not even mentioned in this category.

Initial concepts of ‘collaborative’: Good connection on either side, sharing of knowledge, training sessions or guidance, master classes, routine, well organised work events, teach everyone to use full functionality of useful platforms, people, connection, communication, knowledge, experience, digital tools, white boards, post-its, my phone (camera), people I work with well, clear communication with co-workers, ping-pong of ideas, brainstorming, role-defining, dividing work clarity, short meeting instead of chat/ emails, constructive suggestions, no competition, clear task for everyone, equal chance for everyone to speak on Zoom.

Social-based: 9

Knowledge-based: 7

Organisation-based: 4

Physical-based: 3

Feeling-based / mindset-based: 2

Technology-based: 2

Environment-based: 0

Time-based: 0

Total: 27

Words associated most with ‘collaborative’ proved to be, unsurprisingly, in the ‘social-based’ category. ‘Knowledge’ was the second highest, with seven. ‘Environment’ was placed bottom, emphasising the dichotomy between ‘focus’ and ‘collaboration’.

In the next step, we asked participants to narrow down their list of words to what was most important to them according to how they defined their workday. The list was narrowed down to:

Combined and prioritised list:

Brightness / day / nature, routine / cut-off time, fast wifi / software, collaboration, communication, podcast, getting out, teach everyone to use digital platforms, a good work-home setup, access to printers and scanners, more space to make/grow exercise, flexible working hours, focus, time, nature, light, information, flexibility, autonomy, collaborating with people who I connect creatively with, enough time, wifi, to-do list, clear communication, access to resources or tools, nature of inspiring environment, good food, news, food, walk, family, update, food, read.

Social-based: 7

Environment-based: 6

Knowledge-based: 6

Physical-based: 5

Organisation-based: 3

Time-based: 3

Technology-based: 3

Feeling-based / mindset-based: 1

Total: 34

In tallying the prioritised list, ‘social-based’ words came out on top, with seven, and the least prioritised were ‘feeling-based / mindset-based’ words, with one. Obviously, there is much overlap between many of these terms. The ‘feeling-based / mindset-based’ words can be interpreted as a result of many of these other words.

When looking at the collection of words as a whole, categorisation of the meaning has the potential to change. ‘Moments’, for example, can fall into the category of ‘feelings’ as well as ‘time’. When looking at the meaning of these words, interpretation has to be considered through a prioritised lens.

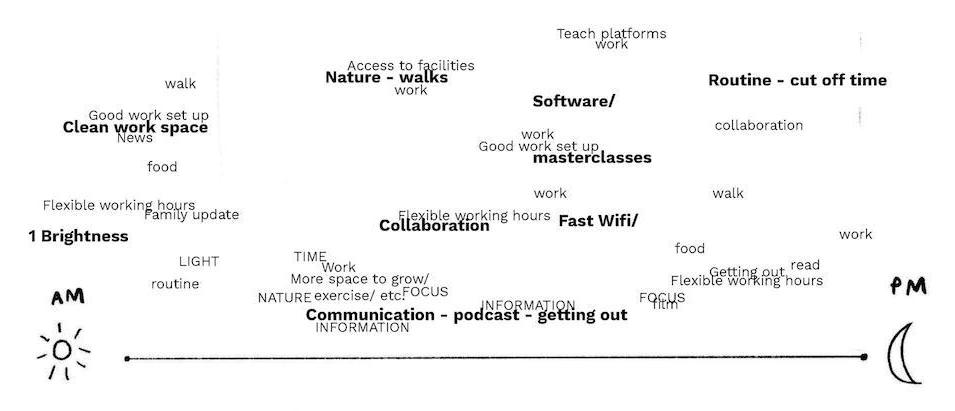

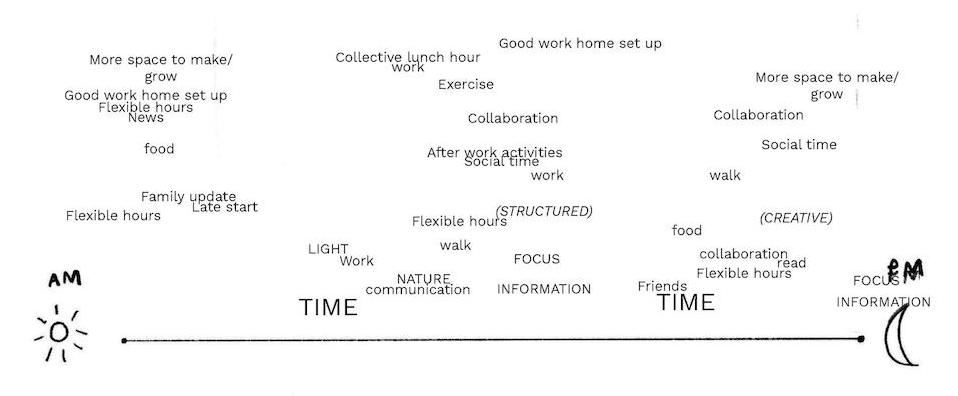

As a continuation of these exercises, participants were asked to display their final words across the day, according to their importance for them, or how much they appeared during a typical workday: both during and (hypothetically) after the Covid-19 pandemic. The importance of brightness or natural light and a clear workspace helped at the start of a workday, followed by the effectiveness of having a good wi-fi connection that allows for uninterrupted workflow, as well as the correct software and work tools. The presence of music or elements that happen in parallel, such as food or the presence of nature, appeared to be key assets of focus. During discussion, we picked up how routines of monotonous and static work needed the aid of cut-off time to add dynamism to the day and improve effective focus time: for example, walking, exercising, family updates, films or masterclasses. All of the aforementioned couldn’t have happened without flexible working hours, in which each person is able to perform their own routines and, with co-workers, time their peak productivity periods during the day.

Part II: Results

At first glance, not much changed from the current situation to the ideal setting, but one can highlight changes from having more space to grow, reading and communicating, as well as a longing for regaining social life. Clearly, flexible hours still prevail as something that needs to develop and incorporate into the future of work routines, as well as walking and the possibility to work from home regardless of the pandemic.

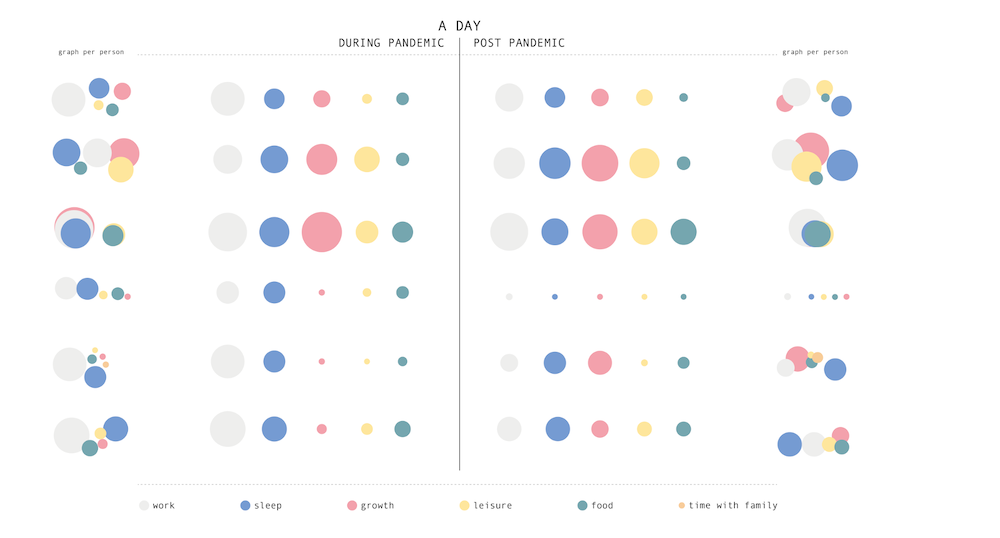

The next exercise involved a reiteration of Part II but focused on the ideal post-pandemic scenario. Occupying a blank space representing the duration of the day were five different circles of activities: work, sleep, growth, leisure and food. Participants could shrink or stretch each circle as desired to represent their everyday average course of action, resulting in not radically different representations among the participants.

When comparing the participants’ maps of their workday during the pandemic with their ideal post-pandemic scenario, one can see how in all cases, the workload diminished to allow more space for other activities. Sleep appeared to have the least variation, followed by food. However, what changed was not so much the proportion of these activities compared with others but rather the relationship between themselves.

Some participants did not occupy the whole of the blank space but instead focused on the size difference between circles. One participant’s post-pandemic activities were equally laid out in exactly the same proportions, yet they were small in relation to the white space, while another participant overlapped their activities and almost occupied the entire day space. As we could see, each participant had their own style in arranging the activities as a whole; however, they were not dissimilar when measuring individually. [See figures 3 and 4].

Part III: Results

As a final individual exercise, in Part III, participants selected images from an interactive image board, which served as a trigger to a concluding conversation. Each participant deleted the images they found superfluous or not as predominant in their ideal future workspace, and its relationship to their everyday lives. As shown in the bottom of figure 5, the images that appear more visible were more predominant among participants: a green space with food harvest; an isolated cabin in a forest; a cup of coffee and a computer in bed; a meeting with more people; a park; a museum; and cycling in the city. We then discussed how certain creative processes were lacking a connection with urban and social lives, as well as with a cultural space for inspiration. It turned out that wide space and connection with nature overtook the conversation and made clear how we’ve all had to understand our lives in relationship to nature – all the way from leisure and sports to nutrition.

Discussion

Over the course of the workshop, the group, both as participants and as the collective, shared thoughts about their current workday and the pros and cons of what they were experiencing.

A few notions were predominant during the conversation and upheld certain assumptions while a number of questions were also raised:

1. The materiality/physicality of the work environment

Do we identify work as an energy or rather an organisation?

What does this mean for designers of the built environment?

2. Flexibility and freedom: the ability to rearrange and curate the dichotomy between work and non-work moments

How do we want to engage with work and collaboration environments after this pandemic, and adapt to working from home on a more flexible schedule?

One of the participants shared her excitement for the future of work, having noticed how people are making up their own work lives owing to the current situation and the necessity of adapting work to other contexts. Another participant raised how interconnected she found her activities to be in her ideal working future, in a space that provides an opportunity for growth.

The shift in transitions between activities and the repercussions on the urban environment was also discussed.

Questioning the relationship between location, time and activities became more relevant after having carried out the aforementioned activities, as participants analysed their work culture patterns and how they had changed over the pandemic. But even if it may sound obvious, we all wondered how distinct forms of work life and culture will take shape from now onwards.

What Jacques Tati once illustrated in his movie ‘Playtime’ now appears as an absolutely fictional and remote setting. However, if reading this image differently, we’re not that far from being isolated within four walls and a few inches of glass portals, which take us across the world on cybernetic travels. The conversation raised awareness of the role that office space could occupy at an urban and economic scale, as well as the role of designers in helping reshape working environments in the near future. What happens to the real estate market when workspaces have become superfluous? Will there be a reinvention of the city programme as space for offices, corporations and co-working redefine their proportions in relation to working from home? Will rush hours dissipate from the physical world and rather become targets for online marketing, resulting in network connectivity traffic jams?

3. Consciousness

How do we make sense of what we have to do? How does it fit into a bigger picture that includes personal growth?

Being spread out across the globe since our very beginning, we were already familiar with creative practices at a distance and as a team. Since branching off from London, our current international collective has had to confront working collaboratively from a distance, with building an interdisciplinary project that might only comprise in the short term a digital reality, and of organising itself well enough to enforce a connection of research and practice. This has led to questioning concepts from the start, attempting to find our way in comprehending work. This workshop could potentially lead to answers to larger questions regarding potential growth, and opportunities shaping the relationship to the built environment.

About the authors

Nuria Benítez is an architect from Mexico City, exploring intersections between design, art, craft, society and urban theory in the everyday. She currently works as an independent architect and researcher in various collaborations, and is a co-founder of estudio estudio. In her masters at The Royal College of Art, she studied urban justice using mapping as a critical tool to leverage contested territories in urban development and trigger participatory tactics to claim agency to design the city. Rime Cherai has a finance and economics background, having graduated from Toulouse Business School and the Universitat Politècnica de Cataluña. While studying at the Royal College of Art in London for her masters, she explored rural areas in emerging countries and possible design intervention to foster their socio-economic development. Jonathan Gayomali is a designer from Los Angeles who also graduated from the Royal College of Art in London, where he investigated the role of design and architecture in the context of social interaction and communication. He has since started practising at New York and Los Angeles-based architecture practice, MarmolRadziner. All three are members of interdisciplinary research collective, re(s)public collective. As a group, they rethink the narratives of space and its related disciplines through critical design, fine arts and architecture. Aiming to bridge disciplines and look beyond the scission of academia, business and art, they believe in conversation, learning through making, and the future. Their work offers space for reflection on art and creative practice through research.

References

No references

Organisations involved