Cities / Planning and mapping

Energising town centres: Midtown, Selfoss, Iceland – a case study

By David Martin MA, RCA | 07 Dec 2022 | 0

David Martin describes the planning of a new town centre for Selfoss, the largest residential area in South Iceland – the most significant aspect of which was to recreate and rebuild, and, in some cases, move and repurpose a range of buildings.

In many developed countries, the pandemic has accelerated trends that were already in play prior to 2020.

Multi-store retail chains were out of favour and being repurposed, as shoppers went online or started looking for something more experiential, leisure-orientated, personalised or local, versus the ubiquity of more mass-market brands.

Also having a significant impact on town centres and local high streets – some positive, some negative – is hybrid working, which seems here to stay. The traditional community mall or local shopping centre – once the epitome of newness and innovation – have lost relevance, and have either been closed and bulldozed or are in the throes of major repurposing, often involving a larger leisure and entertainment element.

An island nation situated in the North Atlantic between America and Europe, Iceland has a population of 300,000, which not only punches above its weight in GDP per capita (ranked in the top-ten for nominal) but is also influential in many other ways. Icelanders, who have a huge thirst for travel, blend outside ideas and influences with their own individual philosophies, ideologies, and Nordic sensibilities.

As a consequence of its work with real estate property owners, M Worldwide was introduced to Sigtún Thróunarfélag, a development company founded by two entrepreneurs in 2014, with the idea of developing a very individual scheme – a new “old” town centre in their hometown of Selfoss in South Iceland.

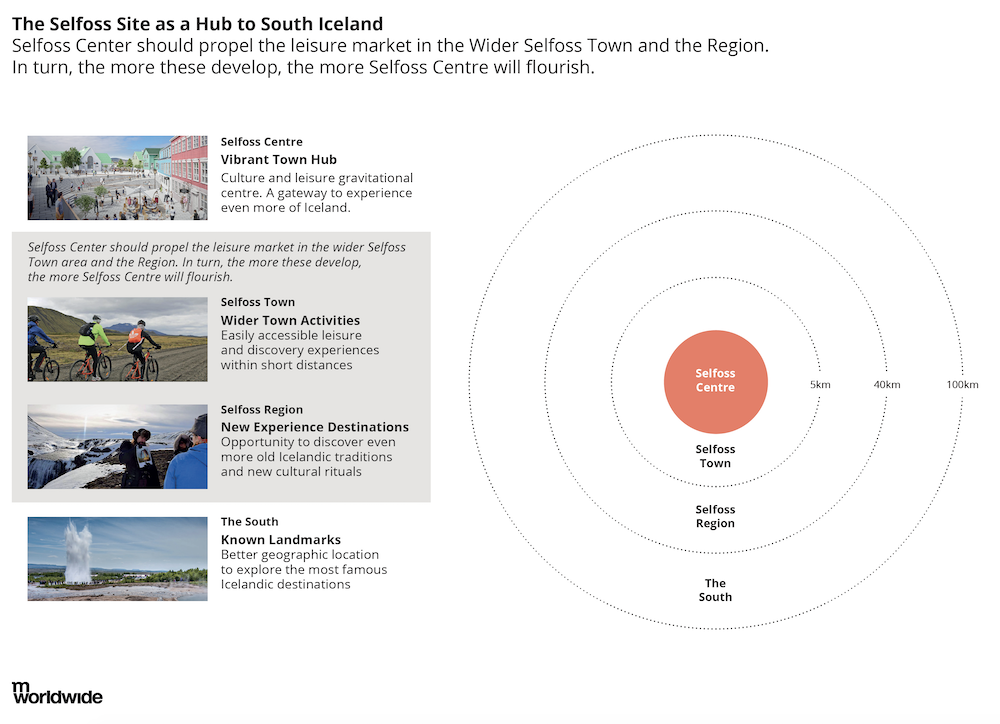

Selfoss is a town set on the banks of the impressive Ölfusá river. The seat of the municipality of Árborg, Selfoss is a centre of commerce and small industries with a population of 9000 (2021), making it the largest residential area in South Iceland.

Located about 11km inland from the southwestern coast, and 50km from Reykjavík, it provides a gateway to the natural wonders of the south of the island. Most visitors undertaking the famous ‘golden circle’ tour of Iceland’s natural features will have passed through.

Over recent years, Selfoss has seen sprawling development for both light industry and residential, bisected by a major road (Route 1), which takes all traffic to the south of Iceland.

Icelanders joke that, historically, there’s been no reason for anyone to stop in Selfoss unless they needed a gas station or a WC – or, as one guide book put it, one of the very best things about Selfoss is how easy it is to leave the town on highway 1!

To help improve the environment for the local population, a bypass is being built with the objective of massively reducing through traffic and improving the quality of the immediate area.

This was the catalyst for local developer Sigtún to create a concept to establish a new ‘old’ town centre. The original vision is described by the company as follows:

“Some towns are old, and some are new. But in Selfoss, the past connects with the present in a truly unique way. We look forward by looking back.”

“Thirty-five historic buildings, previously damaged by fire, or had fallen into disrepair, are being reconstructed to form a unique cultural centre.”

“Cutting-edge architecture is set against the panorama of Icelandic history. Within a one-hour drive of all Iceland’s major nature attractions in the south.”

“Opened in 2021, the new Selfoss Centre hosts shops, restaurants, hotels, and cultural activities of different kinds.”

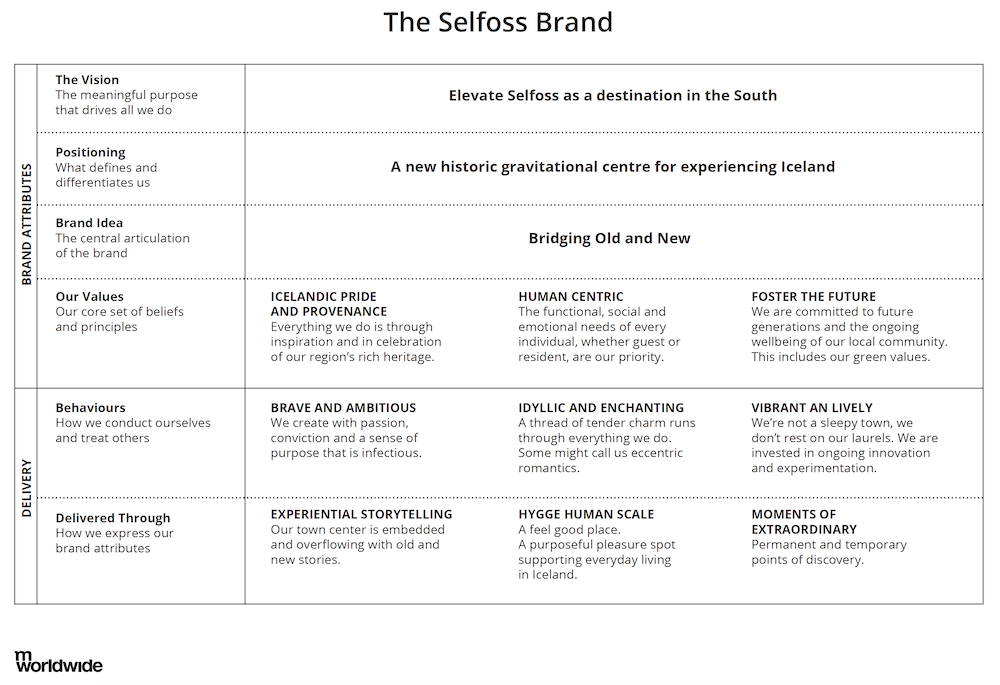

M Worldwide joined the project team to bring an additional perspective – one that focused on end users of the scheme – and to develop some key principles that would help ensure the success of the scheme.

In the course of its work with developers, the company often considers buildings and infrastructure as “hardware”, driven by “software” developed using its own diagnostic and Futureback processes. In essence, the company crafts the strategy for the end user experience – carefully curating the scheme on a number of levels to ensure relevance and appropriateness, as well as devising a design vision with guiding principles that can evolve organically.

Phase 1 of the 5000m2 scheme opened in 2021, with Phase 2 planned to open in 2024, creating an additional 22,000m2.

As we reflect post-Covid about changes taking place in other town centres and high streets, there are some significant ideas that could be transferrable to urban settings elsewhere.

The proposition

This project really is “placemaking” in its purest form. Built from the ground up on an unloved brownfield site, the proposition is formed around a simple single idea: to build a new “old” town centre. The town centre that Selfoss has always lacked.

What has been created is a virtuous circle: a new town centre seen as important social enterprise and focused on creating a place where people want to spend time – work time, leisure time, or just time visiting, which in turn leads to commercial success, and so on.

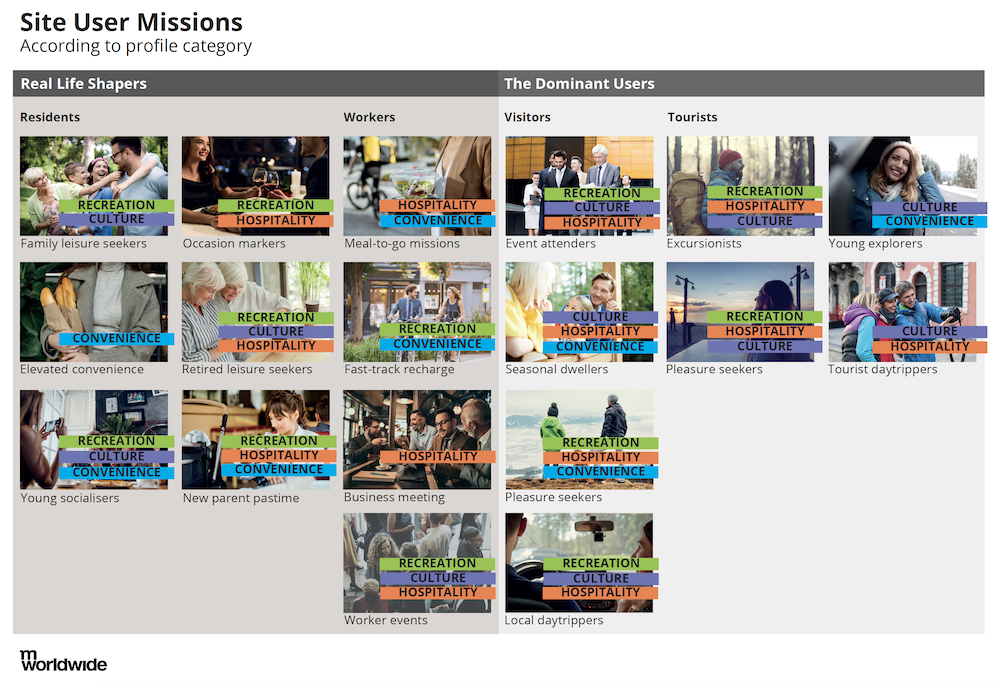

Through extensive community consultation – with the municipality, residents and businesses, including a Selfoss-wide referendum on whether the community wanted this scheme – detailed segmentation, studying relevant best-in-class examples, and by assembling a diverse group of expert partners, a specific ecosystem with a new set of principles has been realised.

The model

The development of this scheme has never deviated from its end user focus: to understand how this place can be relevant and organic. The right mix of tenants and sectors has been carefully curated to ensure that there are always relevant destinations and events to attract and compound footfall. Partner organisations and businesses are carefully selected to ensure they’re committed to actively contributing to being part of an organic, socially focused concept – for example, choosing an independent hotel versus bigger chains and successful restauranteurs proven to be able to run two or three locations successfully – side-stepping the unpredictability of the restaurant starting up or the anonymity of the larger chain. Revenue is generated as a percentage of turnover with an acceptance that the contribution may be very uneven across tenants, allowing bigger established brands to co-exist with small independents.

Human scale

The most significant aspect of the development was to recreate and rebuild and, in some cases, literally move and repurpose a range of buildings based on Iceland’s traditional vernacular style.

These reconstructions showcase what came to be seen as the classic Icelandic style, including characteristic corrugated iron facades and chalet-style architecture. In fact, this ‘Icelandic’ style combines influences from Scandinavia with an addition from the United Kingdom. British ships would bring corrugated iron to Iceland to trade for sheep, and it turned out to be a suitable building material for the climate. The chalet style has a Norwegian influence, itself inspired by country chalets in Switzerland and known as Sveitserstil.

All the buildings that form the first part of the town centre development are recreations of houses that have disappeared, with the history of each one displayed on each building, adding to the overall experience.

These create a development of an intimate and human scale, interwoven with largely car-free walkways and lanes. Many buildings are based on actual original buildings that have a strong history and provenance. And the buildings themselves, their juxtaposition, as well as materials and colours, create a rich variety and texture that is both simple and familiar.

The outdoors

Since the first phase of the new town centre opened, there has been significant change in Selfoss. The city centre has generated a lot of attention and attracts many people – locals, people from the greater Reykjavik area, as well as domestic and foreign visitors.

In the new town centre, a platform has been created for outdoor activities, events, and outdoor gatherings in the town, with a carefully designed public realm, including a focal sunken amphitheatre carefully detailed to protect users from the unpredictable and often harsh Icelandic weather.

Connections with other neighbouring facilities and areas, such as the central park and the local sports area, have been carefully established to ensure an integrated symbiotic relationship – where the whole town centre is seen as a wider, blended ecosystem, rather than separate entities.

The new scheme also encourages use of nearby natural leisure resources and surrounding countryside for walking, running and cycling, as well as us of the Ölfusá river. These incredible natural resources have been somewhat overlooked, as the main highway route one was an intensely urbanised area with a range of functional, commercial and residential building that vary in quality and design. There is even discussion about a possible cycle route to link Reykjavik and Selfoss.

The next phases of the town centre development are now in progress – and the halo effect of what has been created so far is influencing other important areas in the town centre. The main town and thoroughfare and streetscape will be reimagined to encourage dwell time, and enhance the experience for residents and visitors.

Green credentials

Environmental and green issues are a central pillar of the midtown development approach, and the extent of these far exceed the traditional requirements of the legal and regulatory environment for construction activities and planning.

Striving for the highest environmental standards, leading to recognition by reputable international certification bodies, has guided the project throughout the entire process. This is unusual for a small developer, as dealing with a number of existing structures to be relocated and repurposed situated on a rather neglected brownfield site entails significant additional costs.

So far, the scheme has received the Nordic Swan Eco Label from the Icelandic Environment Agency for certification of all buildings in the new centre of Selfoss.

This is the largest single project to have received Swan certification in Iceland and covers 13 buildings with a total of 5500 square metres. Certification ensures that all building and chemical products used in the construction are environmentally verified – down to the smallest items, such as nails and screws, which must meet strict requirements for the content of harmful substances.

Swan certification also ensures that the environmental benefits of the project are significant; for example, in this case, the use of environmentally friendly concrete meant that around 170 tons of carbon equivalents were saved, which corresponds to the annual consumption of about 50 passenger cars.

Through the construction process, emphasis was placed on sorting waste and preventing energy wastage; an air exchange system with heat recycling was installed in all apartments. Special emphasis was also placed on moisture prevention and procedures to prevent moisture damage and mould, with building materials’ moisture measured and building airtightness tests carried out. These points are important to ensure the best possible end user environment with regard to air, sound, and light quality. The main contractor, Jáverk, has built a significant body of environmental certification knowledge through the project so far, and will apply this to a further 430 Swan-certified apartments this year.

The project has also received a BREEAM Communities certification for sustainability of the central district. This certification standard covers specific areas where multiple structures are located, enabling the design teams, developer and planners to improve, measure and certify the sustainability of the city centre at the design and planning level.

There is a strong focus on influencing sustainability through public engagement, policy and design. Subject categories assessed in the BREEAM Communities certification of the city centre include: consultation and governance; social and economic wellbeing; resources and energy; land use and ecology; transport; and movement. Icelandic experts in various fields prepared detailed reports for Sigtún on each of these issues.

There is huge focus on businesses and organisations to ensure green, environmental and ethical values are at the core of what they do, especially as end users – be they residents, businesses, employees, or visitors – are beginning to vote with their feet and choose brands, places and organisations that demonstrate and share their values.

As a country on the edge of the Arctic Circle, with an extraordinary natural landscape and which uses only geothermal energy, Iceland must follow an exemplary approach to green and environmental issues to ensure its image of natural purity is maintained.

The life and soul

For too long, new schemes have been reliant on beautiful buildings to create a place – “if you build it, they will come”. However, to compete with the digital world, where content is constantly changing and evolving, new schemes such as Midtown must embrace the need for compelling and engaging content on an ongoing basis. Tenants and partners are selected partly on their willingness to contribute and get involved – where it’s everyone’s job to create reasons to visit and return. To this end, leisure and entertainment facilities are a central part of the mix, with various venues, including jazz bars, theatres and an extensive programme of curated outdoor events – live screenings, Christmas markets and artisan workshops – all adding to the rich buzz.

The ripple effect

While on the drawing board, this scheme was not without its sceptics. Like many new and inventive projects, there are plenty of detractors pointing out flaws, downsides and reasons why it was not appropriate.

“Will it ever be built?”; “Is it right to look back and focus on these old buildings?”; and “It’s all a bit Disneyland isn’t it?” are some of the doubts and criticisms heard.

But the focus of the Sigtún team has seen the first phase delivered to great applause. Many beyond the Selfoss community are embracing and celebrating what has been realised – from the drawing board to reality in less than three years.

There has also been a positive ripple effect, too. The municipality is starting work on an extended masterplan for the greater Selfoss area and local businesses are actively looking to contribute to this civic movement. Adjacent landmark buildings are starting to be repurposed. The regional Landsbanki building – iconic architectural buildings around the country designed by state architect Guðjón Samúelsson – has, for example, been repurposed into shared co-working space. Both the Icelandic Government and the local Arborg municipality are both partners with Sigtún in this project – with a large proportion taken by Reykjavik council to provide flexibility for council workers so they can avoid the need to commute into the capital.

The design

Sigtún, like Apple, knows the value of design as a business tool. Ahead of architecture, build costs and rental yields, this scheme has invested in experience and environmental design; researching and celebrating the repurposed building history; investing in the public realm and landscaping; and ensuring the experience and content are worth stopping to enjoy.

One of the scheme’s landmarks is the Old Dairy, reconstructed in 2020. The original dairy, which was also designed by Samúelsson, started operating in Selfoss in 1929. The dairy collected milk from the cows of local farmers to produce fresh milk, cheese, cream, whey and skyr.

The new Old Dairy is now a buzzing food hall, offering a diverse range of food and drink brands in an environment curated with architectural and industrial reclaimed items from across Europe.

The basement hosts a boutique museum that celebrates Selfoss as the home of skyr. Called Skyrland, it takes visitors on a journey of sights, scents and tastes, where they can discover the 1000-year story of how a Viking dairy product became a global health food.

Summary

Like many things, timing is everything. This scheme, one could say, was conceived and developed at the right time – or perhaps, it’s just a result of an emerging zeitgeist.

The scheme bridges the old – traditional buildings; history; nostalgia and a cosy familiarity; a geographic gateway; foods; crafts, materials and finishes; and artisans – and the new. This new includes: a town centre; jobs and business opportunities; social and leisure activities; an outdoor shopping mall; a heart and destination; a hub from which to explore the south of the country; services; a place to stop and meet; improved quality of life for local people; and a showcase for Icelandic ingenuity and innovation.

With changing societal structures and fresh ways of thinking about town centres, dynamics that have been fuelled and accelerated by the pandemic, this scheme demonstrates what can be achieved if a focused team keeps the faith to realise a project that the nation and end users can fall in love with.

About the author

David Martin MA, RCA is director and co-founder of M Worldwide.

Organisations involved