Cities / Community resilience

Co-designing a greener, fairer and stronger community for children’s wellbeing

By Matluba Khan, Thomas Aneurin Smith and Neil Harris | 15 Dec 2022 | 0

This article, authored by Drs Matluba Khan, Thomas Aneurin Smith and Neil Harris, presents a short case study of co-designing a neighbourhood with children and young people to generate a greener, fairer, and child- and youth-friendly community in Grangetown, Cardiff.

Authors of scientific paper:

Abstract

Measures enacted to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic, including social distancing, school closures, and the prohibition on outdoor activities, have accentuated social and spatial inequalities, particularly for children and young people (CYP). The experiences of CYP living in overcrowded households, in high-rise flats, and those with no access to gardens and with limited/no access to the internet are evidently not the same as children living in a spacious household with access to ICT, a private garden, and a high-quality park. Evidence suggests there will be long-term detrimental effects of the pandemic on CYP’s health and wellbeing1.

Communities will need a recovery plan for coming together and regenerating outdoor sociability and green-space access for children and young people. Cardiff University has partnered with the Child-Friendly Cardiff Team of Cardiff Council, Community Gateway, Grange Pavilion and Grange Pavilion Youth Forum, to work with children and young people from Grangetown, a community in the centre of Cardiff. Their aim is to co-produce a greener, fairer and child-friendly recovery plan through a series of workshops involving creative methods.

Activities are conducted in four distinct phases:

- co-assessment of neighbourhood quality through application of creative methods, such as mapping, drawing and child-led photo-walks, and which also includes an exploration of children’s feelings and emotions as to how the pandemic-associated responses have affected their daily lives;

- co-creation of a phased recovery strategy through model-making, with methods adapted to be age-appropriate;

- co-building of one element from the recovery strategy with direct participation of CYP; and, lastly

- co-creation of an accessible toolkit for planners with inputs from CYP, reflecting the learnings from earlier phases.

The activities were conducted between March and June 2022, and this paper will share the findings from the first two phases of co-assessment of neighbourhood and co-creation of the phased recovery strategy. Preliminary evaluations of the data reveal that the pandemic has disrupted children’s social network, leading to feelings of sadness, anger, boredom, frustration and being ‘stuck’. In the midst of uncertainties, some children perceived ‘home’ as a safe place, while some others found a visit to the local park ‘calming’. However, children also identified local parks as featureless, where there are ‘not many things to do’. Children’s ideas for a Grangetown to grow up in can be grouped into four themes: clean and safe; playful; green; and inclusive.

A draft recovery plan for a child-friendly community has been developed, which will include recommendations that can be applied in other communities in Cardiff, and throughout and beyond the UK.

Keywords

This study was conducted on the belief that some of the responses and restrictions designed to manage the Covid-19 pandemic – including social distancing, school closures, and prohibition on outdoor activities – have accentuated social and spatial inequalities, particularly among children and young people (CYP). In the UK, and globally, the experiences of children and young people living in different regions, cities, localities and neighbourhoods varied significantly. Indeed, within neighbourhoods, CYP will have had diverse experiences of the impacts of Covid-19, with specific consequences around limits to spatial roaming, time outdoors, and time spent with friends and family, as well as disruptions to normal spatial routines, such as time at school. Evidence suggests that the pandemic will have long-term detrimental effects on CYP’s health and wellbeing1, reinforcing an already well-recognised picture of decline in children’s time spent outdoors in natural, green- or blue-space settings2.

The impact of Covid-19 on CYP’s overall health and wellbeing is therefore unprecedented, but it’s also linked to longer-term concerns about wellbeing and the contribution that places make to the lives of children and young people. At times, during the pandemic restrictions, opportunities for play, social interaction and physical activity were extremely limited for CYP at critical periods of their development. The impacts were likely much worse for children and young people living in neighbourhoods with limited access to green and blue spaces, parks and playgrounds. Children and young people from lower-income, ethnically diverse urban neighbourhoods are likely to have been among some of those most impacted by the pandemic restrictions in terms of their wellbeing, as evidence prior to the pandemic has demonstrated that children from black, Asian and other minority ethnic backgrounds are less likely to spend time outdoors3.

Background

Children’s rights to play and express their opinions have been enshrined by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (Article 13; Article 31) for some time. Public authorities, charities and schools have engaged in valuable work to promote these rights and encourage increased awareness and exercise of them. Nevertheless, the voices of children and young people are rarely taken into account when developing crisis-recovery strategies for cities; more broadly, CYP are rarely directly involved in planning their neighbourhoods. Discussions about the future of places and how to plan them can very easily become adult-focused and centred on a narrow range of issues. The interests, concerns and aspirations of children and young people can struggle to find traction in placemaking processes, despite politicians’ and planners’ ambitions for inclusive participation. This project therefore aims to engage CYP from an ethnically diverse urban community in co-creation workshops so they can envision a children and young people-friendly neighbourhood, while empowering them through their participation in shaping recovery plans for their community.

We worked in the neighbourhood of Grangetown, located in Cardiff, the capital city of Wales. Grangetown is an inner urban neighbourhood to the south of Cardiff’s central business area and north of Cardiff Bay, with the River Taff adjacent to the east. It’s an ethnically diverse area, with significant populations of Somali, Asian and other non-White groups. The population is relatively young compared with Cardiff as a whole. Grangetown is also characterised by a varied housing stock in age, style and quality. Large sections of Grangetown were developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and reflect the urban form of many British cities of this period. The area comprises dense residential development alongside some commercial and industrial uses, with several green spaces of varying size and quality.

The selection of the community of Grangetown for our project was explained in part through a series of existing interventions and projects already centred on the area. Our project was joint-funded by the Cardiff University Civic Mission Fund, and Cardiff Council’s Child-Friendly Cardiff Team, and in collaboration with Cardiff University’s Community Gateway, Grange Pavilion and Grange Pavilion Youth Forum. Cardiff University is already well embedded with the Grangetown community through various outreach, impact and research projects. This reflects a concerted and sustained effort by the University and some of its partners to work with one community over the longer term. Our project involved children and young people (aged 8 to 17) participating in a series of workshops and engagement activities. Through these workshops, we co-produced a child- and youth-friendly recovery plan for the neighbourhood.

How did we perform the study?

This project was carried out through a series of interactive co-production workshops and engagement activities with children (ages 8-11) and young people (ages 12-17) in a variety of settings. Some of the activities with children were carried out in formal education settings, including primary and secondary schools. We also conducted workshops with children and young people in more informal settings during the early evening and weekends – for example, we engaged with members of a youth forum in local community spaces. Additional workshops were conducted with schools in an ‘urban room’, as part of a wider community engagement and participation exercise, alongside some informal drop-in sessions for children and parents. Activities took place between March and June 2022.

They included:

- Co-assessment of the neighbourhoods with children and young people, with an aim to understand where, how and with whom children spend their time, play and hang out in Grangetown, and how Covid-19 restrictions have impacted their everyday experiences.

- Co-creation of a child- and youth-friendly recovery plan for Grangetown that will inform the local authority’s recovery strategy, and short, medium and long-term planning objectives.

- Co-production of a toolkit for planners and designers to equip them with the tools and resources for successful engagement with children and young people.

- Co-building of one element of the recovery plan, designed and chosen by participating children and young people.

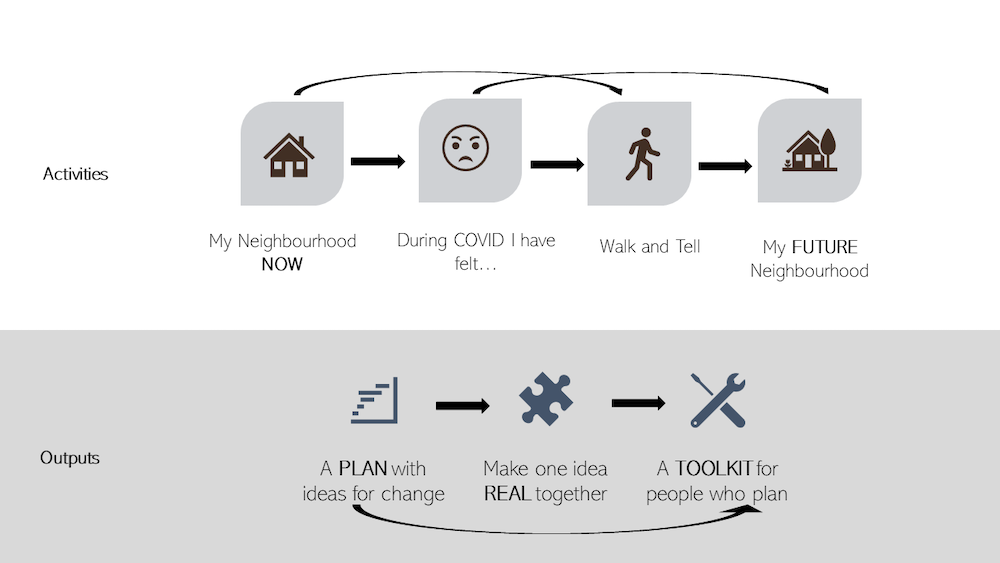

Activities 1 and 2 – the co-assessment of the neighbourhood, and the co-creation of the recovery plan – were conducted through a series of sub-activities illustrated in the top half of figure 1. Children and young people took part in a series of creative methods to reflect on their own understanding of the neighbourhood, and how Covid-19 may have changed how they felt (see figure 2). The range of creative methods included mapping of children’s neighbourhood; drawing imaginary maps of their everyday spaces; child-led photo-walks; and model-making. Children also used these methods in the final workshop to envisage how their neighbourhood could look and feel in future – either through specific interventions or through annotating their ideas for physical and social change on maps of the area.

The activities listed above and in figure 1 are, at the time of writing, being translated into a series of outputs, some of which are reported in this article. The co-produced Covid recovery neighbourhood plan has been completed, while the interventions of co-building one element of the plan with the contributions of the children and co-production of the toolkit are still in development.

What were the main findings?

We expand below on some of our main findings, which can be summarised as:

- Children and young people can clearly articulate the areas within their community that they like and dislike.

- Recreational and green spaces are interesting in receiving mixed evaluations by children and young people – these are important spaces yet participants rated them very differently to each other. Overall, they value green spaces; however, they also highlighted the lack of features available there for play and socialisation for children of different age groups and gender.

- Most children found busy roads and nodes dangerous and not safe while some of them located their favourite shops near the busy places in the neighbourhood.

- Children and young people expressed mixed experiences and feelings about the various ‘lockdown’ restrictions applying during the pandemic. Overall, the lockdown experience negatively impacted on their social lives both inside and outside school, but some found positives from being at home and with family, and not having to go to school.

- Children and young people, when engaged in planning their future neighbourhood, can identify a wide range of changes and improvements that they would like to see in their neighbourhood – and many of these changes extend beyond their own needs to making the neighbourhood an inclusive one for all ages and abilities.

Places we like and we don’t like

Our early workshops focused on how children and young people perceived their current neighbourhood, with a particular focus on places that they did or didn’t like, and the reasons for this. CYP’s favourite places included parks and open spaces, pavilions and gardens, religious centres, local shops, and food places.

Children often listed ‘parks’ in their list of ‘liked’ places, because they can take a walk and play with their friends: “I like Sevenoaks Park. On Saturday, I do like to walk there. Saturdays I play football with Ishak, Paul, George and Andy.” (pseudonyms used for confidentiality)

However, they also identified the local parks as featureless and sometimes boring, where there were ‘not many things to do’: “I like the Sevenoaks Park, but the playground is really boring.”

Children also sometimes felt threatened by other users of some of these places, and there were mixed perceptions about whether the available parks and green spaces in the area were safe for children and young people to hang out or play in.

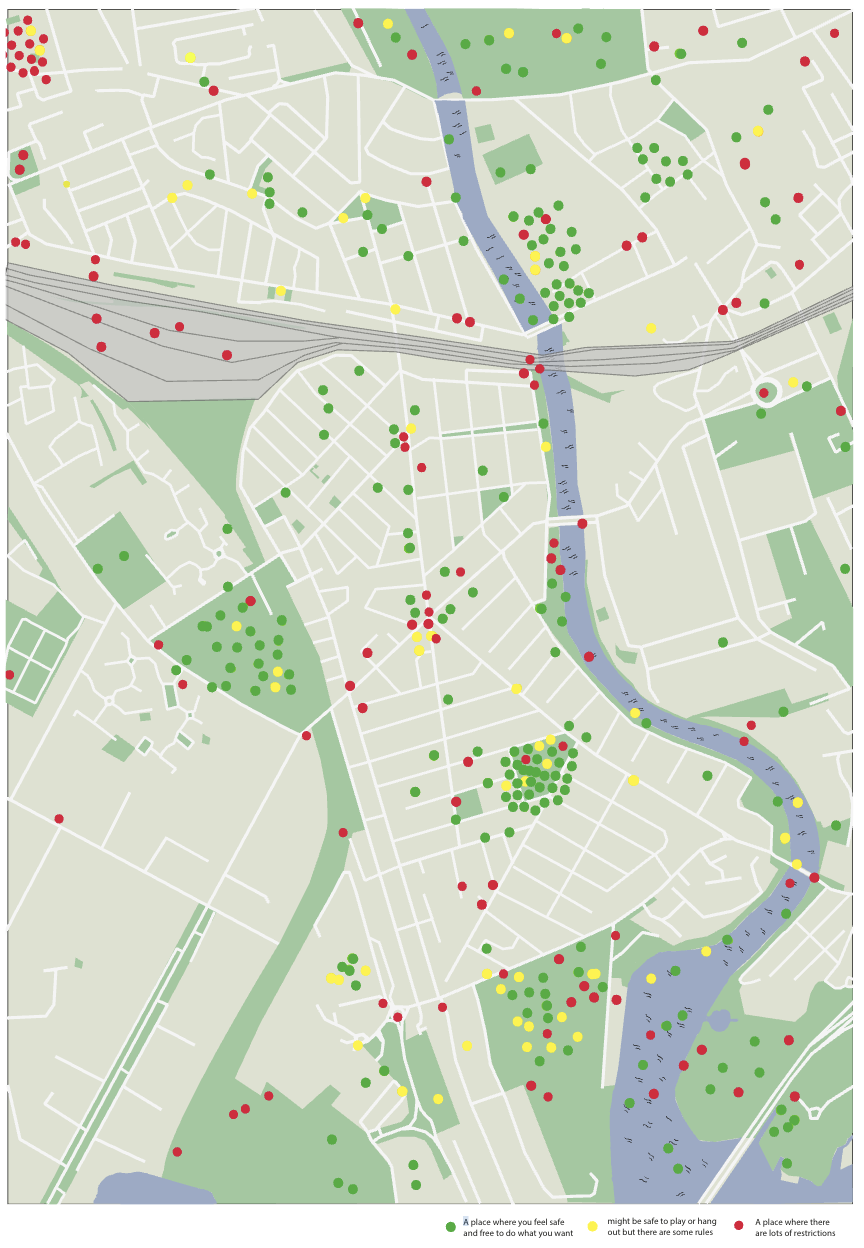

CYP participants identified busy roads and dangerous crossing points, and disliked places that are dark and do not offer a lot for children and young people: “Penarth road is dangerous, it’s unsafe to cross the road, long and boring.” Busy intersections on roads were also identified as places they disliked; and for some young people, they didn’t like their school (the secondary school is located in the top left of figure 3, below).

These early exercises conducted with the CYP assessing their neighbourhoods demonstrated that the participants could have strong likes and dislikes for particular places, but that there was often ambivalence and mixed opinions. While many highlighted parks and green spaces as good places for them (in which to hang out or play), some did not like these spaces (owing to fear of crime or older children, or conflicts with other users, such as dog owners). Busy roads were seen as bad places because they were dangerous and noisy, but some CYP liked them because they had shops they regularly visited, or because they saw friends there while walking to school. It was important therefore to take these mixed feelings and certain ambivalences towards places on board when further drafting the recovery plan.

Life and play during lockdown

Preliminary assessments of the data reveal that the pandemic has disrupted children’s social network, leading to feelings of sadness, anger, boredom, frustration and being ‘stuck’. Not being able to attend regular social spaces, such as going out with or visiting friends’ houses, not being able to go to play spaces, play sports, attend mosque, or go on holiday out of Grangetown, for example, were highlighted as restrictions that impacted them negatively. Some young people (less so children) liked the fact that they didn’t need to attend school, but they also lamented not being able to see friends at school. Many young people admitted to not doing at-home learning, and that they just “stayed at home doing nothing”.

In the midst of uncertainties, some children perceived ‘home’ as a safe place, while others found a visit to the local park ‘calming’ or ‘relaxing’. There were some positive stories, too, as some children mentioned they were happy and relaxed, as they could spend more time with family. As with their ideas for most liked and disliked places, CYP expressed some mixed feelings about the pandemic. One wrote: “During lockdown I felt bored and it was sooooo fun”; while, for another: “I felt quite happy because I don’t go out much.” Others clearly expressed the stress, worry and anxiety of the pandemic. One wrote: “It really got me worried because it killed a lot of people and I thought that would happen to my family and friends.”

As with their reflections on their neighbourhood, CYP participants expressed mixed experiences and feelings about the pandemic. Overall, it negatively impacted on their social lives, both inside and outside school, but some found positives from being at home and with family, and not having to go to school. While some reflected very negatively on the restrictions, a few found opportunities and spaces to relax outside in local green spaces. The exercise also revealed some of the specific places that CYP valued as social spaces and times, such as playing sports, going to religious places of worship, visiting play parks, and the importance of their homes.

My future Grangetown: A Grangetown to grow up in

Over the course of our workshops, CYP’s ideas for a plan for the future of their neighbourhood – titled ‘A Grangetown to grow up in’ – crystalised into four themes: clean and safe; playful; green; and inclusive.

Drawing on their reflections of the neighbourhood, the participating children and young people developed a series of ideas for improving the area to make it more child- and youth-friendly. Some of these related to specific post-Covid interventions, while others were focused more generally on improving the area for them.

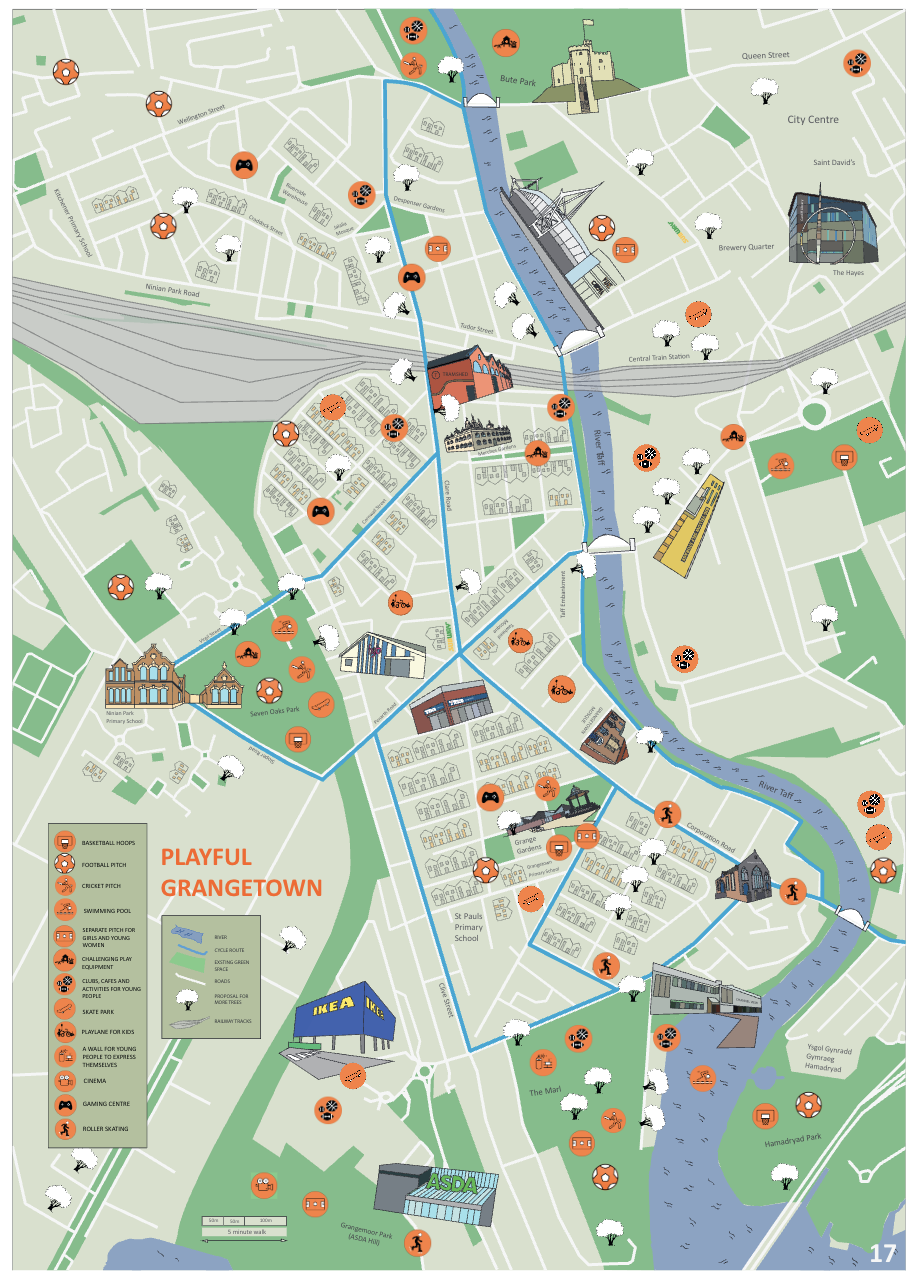

Their ideas for a clean and safe Grangetown include safe and clean streets, smooth roads and footpaths, and safe neighbourhoods, broadly addressing their safety concerns of hanging out and playing in open spaces, as well as moving around the neighbourhood safely (many walked to school, for example). They aspired for a playful Grangetown that would offer opportunities for play and activities for people of all ages: play lanes for young kids (the layout of the area means many rear access lanes between properties); clubs, cafes and activities for teens; sports facilities for girls and young women; age-appropriate play equipment; and inclusive play spaces. In particular, several children highlighted the need for spaces to be accessible to those with physical and learning disabilities, as well as spaces for play and hanging out where young women feel safe. Some focus in this area was also on either improving existing play infrastructure, or restoring some facilities that had been lost (e.g. football pitches).

Ideas for a green Grangetown include opportunities for green and active travel, improving existing parks and playgrounds while creating more green spaces, and increasing the biodiversity of the area. CYP were focused on improving existing park spaces, as well as introducing greening in and around street spaces, and they had an appreciation for improving the diversity of plants and animals they saw in the environment. An inclusive Grangetown, according to children and young people, can be built by offering safe spaces for women, e.g. a women’s-only cafe, providing mental health help centres, offering activities for elderly people, and designing for people with all abilities.

For each theme, we developed a map based on the mapping exercise with CYP during the workshops. Figure 4 demonstrates one of these thematic maps, for a playful Grangetown. The symbols used draw together themes suggested by the young people, and CYP used similar stickers themselves during some of the activities. Ideas for placing sports pitches and play spaces (including more challenging play spaces) featured prominently on this thematic map, but CYP also highlighted the need for indoor play areas, such as video gaming centres, as well as walls where young people could do street art, and dedicated ‘play lanes’ where children could play safely.

Why are these results important?

- The project was successful in showing how to give voice to children and young people in the planning of their neighbourhoods: Many participants shared that this was the first time anybody had asked them about their opinions of the place they live in, or about how they had felt during the pandemic. They felt positive about the fact that the outputs of the co-production process would be taken seriously, and that an intervention would come out of the project as a first step.

- The project results demonstrate the possibilities of creative methods for co-produced neighbourhood plans: CYP are the experts of their own lives and the recovery plan created is reflective of what children and young people envisage. The creative methods we used were flexible and varied, enabling a diversity of expression, and they didn’t pre-suppose what the CYP participants would identify or design.

- The results show appropriate design of engagement activities can empower participants: While we did not measure or record systematically feelings of ‘empowerment’ as part of this project (in part due to the complexities of this), anecdotally, CYP expressed some positive feelings about their engagement with the project and their hopes for the future. This was notably more common among children than young people who participated. We noted that some young people expressed frustration at having spoken up prior to our project to various community representatives about their needs, but they had not seen any practical action in response – many therefore felt ignored or not listened to prior to the project.

- The project results are contributing to the design of a toolkit, which can be applied across many communities: The toolkit in development will enable other communities within and beyond Wales to co-create plans for child-friendly neighbourhoods, based on the flexible creative methods and workshop format we used.

- The project identified important challenges in designing and realising child-friendly neighbourhoods and cities: Children and young people expressed mixed feelings and ambivalences about particular spaces, activities, and their neighbourhood more generally. They did not always agree on interventions or ideas expressed by others. Some found it difficult to prioritise their needs, or to envisage the practical steps towards what some of their proposals would look like or how they could happen. More work is needed on the practical interface between children, young people, planners and developers when considering CYP’s engagement in these areas.

What’s next?

There are several next steps for the project:

- We will develop our neighbourhood recovery plan into a more detailed action plan to implement the ideas shared by children and young people – identifying the various organisations and partners that can help make the plan a reality.

- We will be facilitating a dialogue between the children and young people of Grangetown, and the councillors and officers of the local authority – designed to help implement the neighbourhood recovery plan and hold those in power to account on delivering the ambitions and aspirations of children and young people.

- We’re working on implementing one of the specific ideas for action and improvement identified by children and young people – both as a way of illustrating that change is possible and so that participation and engagement in exercises can make a practical difference, with results on the ground.

- We plan to disseminate the toolkit developed for working with children and young people so that it can used by others – including children, young people, youth forums, urban planners, and councillors – who want to develop a plan for their own neighbourhood.

About the authors

Dr Matluba Khan is a lecturer in urban design at the School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University. Dr Thomas Aneurin Smith is a senior lecturer in human geography, at the School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University. Dr Neil Harris is a senior lecturer in statutory planning, also at the School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University.

Funding

This project was funded by Cardiff University as part of its Innovation for All programme, and by Cardiff Council through its Child-Friendly Cardiff initiative. The project formed part of the Community Gateway scheme delivered by Cardiff University, and was delivered in conjunction with Grange Pavilion and Grange Pavilion Youth Forum.

References

- Cowie, H and Myers, C-A. (2021). The impact of the Covid‐19 pandemic on the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people. Children & Society, 35(1), 62-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12430

- Soga, M, Yamanoi, T, Tsuchiya, K, Koyanagi, TF, and Kanai, T. (2018). What are the drivers of and barriers to children’s direct experiences of nature? Landscape and Urban Planning, 180, 114-120.

- Natural England. (2019). Monitor of engagement with the natural environment: Children and Young People report.

Organisations involved