Mental/behavioural healthcare / New models of care

Capitalising on modularity to solve a mental health crisis

By Maria Ionescu | 26 Aug 2022 | 0

Maria Ionescu considers how standalone modular, prefabricated, crisis units might be rapidly deployed and help address mental health access and capacity issues for health systems around the globe.

Author of scientific paper:

Abstract

‘Teen spends days in emergency department waiting for mental healthcare’; ‘Emergency departments struggling to treat mental health patients’: these aren’t predictions anymore, they are headlines from the past few months. US statistics estimate a quarter of the population will confront a mental health challenge every year. Of those, it’s estimated that half will go undiagnosed and untreated. In the US alone, this equates to 49 million people. Further compounding the problem is social isolation, brought on by the pandemic.

Emergency departments (ED) remain the overwhelmed gatekeepers – the first point of entry into the healthcare system for people in crisis. Data emerging from EDs in the US nationwide show skyrocketing rates of admission for those experiencing a mental health crisis. The average ED wait time for a referral is between seven and ten hours but some patients could wait for days, even weeks, for transfers to the appropriate level of care.

We believe that the rapid deployment of standalone modular, prefabricated, crisis units can tip the scales and address this access and capacity issue for health systems around the globe. For every patient who can be transferred out of the ED into a dedicated modular crisis unit, up to three other patients could be seen and treated in the ED. What’s more, rapid regional deployment in a hub-and-spoke model can serve to address rural healthcare disparities.

These units can be sourced turnkey in a third of the time it would otherwise take using conventional construction methods. Designed for incremental, organic growth as the needs of the organisation evolve, the units retain and recover as much value as possible from resources by reusing, repairing, refurbishing, remanufacturing, repurposing, or recycling products and materials. For many hospitals, this solution also presents an additional revenue opportunity via increased ED throughput. These benefits compound at community scale if we consider that for every patient in crisis, either the police or the paramedics must spend the same average ten hours waiting with the patient in the ED. Once freed, that time could be spent instead on saving lives in our communities.

Beyond strengthening a system’s resiliency and ability to meet mental health needs, the biggest positive impact will be on the patient experience. These modular units, unlike an ED, are designed to be a supportive and calm environment with access to sunlight and nature – attributes that can make all the difference for someone experiencing a mental health crisis.

Keywords

“Teen spends days in emergency department waiting for mental healthcare”; “Emergency departments struggling to treat mental health patients”: these are not predictions anymore, they are headlines from the past few months. US statistics estimate 25 per cent of the population will confront a mental health challenge every year. Of those, it’s estimated that half will go undiagnosed and untreated. In the US alone, this equates to 49 million people. Further compounding the problem is social isolation, brought on by the pandemic.

Emergency departments (ED) remain the overwhelmed gatekeepers, the first point of entry into the healthcare system for people in crisis. Data emerging from EDs across the US show skyrocketing rates of admission for those experiencing a mental health crisis. The average ED wait time for a referral is between seven and ten hours in the US but some patients could be waiting for days, even weeks, for transfers to the appropriate level of care.

A Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) study from 2020, ‘Mental health-related emergency department visits among children aged < 18 years during the Covid-19 pandemic – United States’, shows an approximate 30-per-cent increase in volumes between January and October 20201.

The CDC published a more in-depth investigation of this population segment in April 2022, finding that in the 12 months prior to the second survey, 44.2 per cent experienced persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness, 19.9 per cent had seriously contemplated suicide, and 9 per cent actually attempted suicide2.

What is interesting is that we see this same phenomenon transcending geography and the significant differences between healthcare delivery systems in different countries of the Anglosphere. Here is a quick comparison:

In 2019, spending in the US mental health market reached $225 billion, accounting for nearly 5.5 per cent of all health spending, the lowest level in this comparison3. Some 7 per cent of Canada’s healthcare expenditure is attributed to the mental health system, and despite its universal coverage set-up, the country is experiencing similar challenges. The mental health system has operated for a long time as a patchwork of hospitals, independent providers, therapists, and community groups, paid for through government funding, donations or out of pocket.

Australia, one of the first countries to come up with a national mental healthcare strategy, has been spending about 7.6 per cent in its mental health system for the past 20 years4. The 2018 Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM) survey found that patients with mental health diagnoses could spend up to six days in busy EDs waiting for a psychiatric bed5.

In the UK (13 per cent health expenditure for mental health; the highest in the Anglosphere but relatively low compared with other OECD countries), the Royal College of Psychiatrists has been warning that the number of children and young people being referred to mental health services has doubled during the pandemic. At the end of February 2022, the NHS set out new ambitious wait-time targets for access to community mental healthcare. The proposals published were part of the NHS Long Term Plan’s commitment to service expansion and improvement for mental health. Under the Plan, patients with an “urgent” mental health issue, regardless of age, would be seen by community crisis teams within a maximum 24 hours, while for those triaged as “very urgent”, the wait time would decrease to four hours. The work around determining the ‘how’ of these targets being achieved is just starting and most would agree that meeting them will require a lot more investment in services and workforce.

We believe a lot of the rapid-response lessons learned during Covid can be readily applied to responding to this mental health pandemic. Around the world, the most resilient healthcare systems have been the ones with a distributed, robust presence in the community, as they were capable of converting assets and scaling rapidly.

We believe, too, that the rapid deployment of modular, prefabricated, crisis units (either standalone or attached to a hospital) can tip the scales and address the access and capacity issues for health systems around the globe.

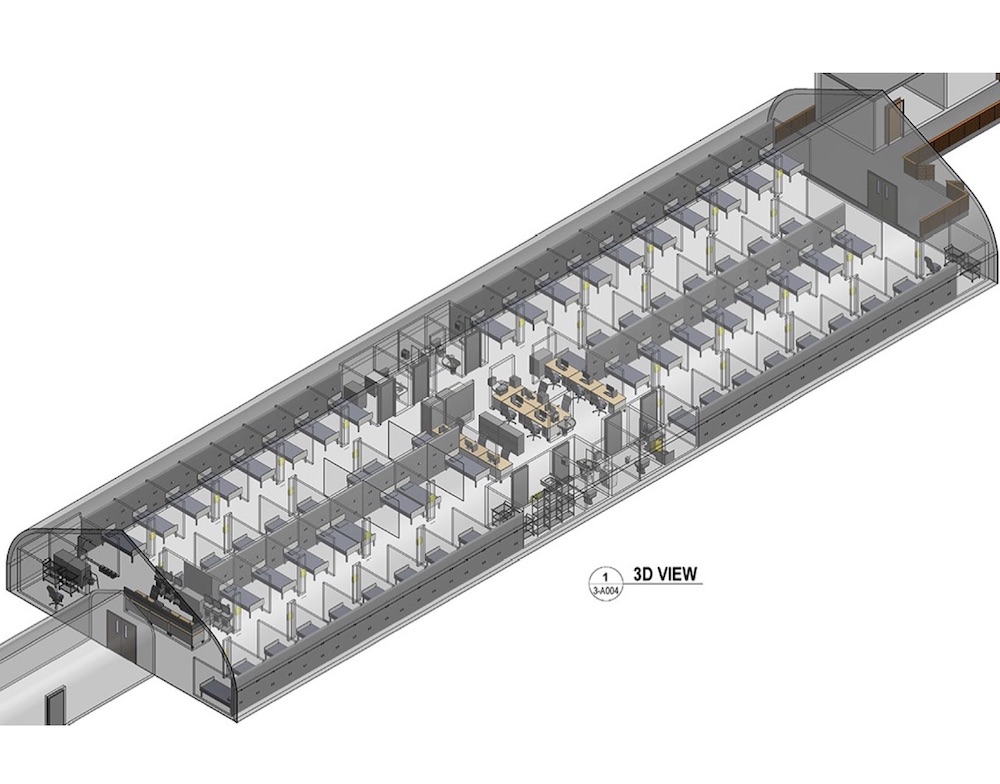

A good example of a successful conversion of structures delivered part of the Covid response for the continued alleviation of flow and capacity issues in the ED: the Pandemic Response Unit (PRU), designed by Stantec for the Peter Lougheed Hospital in Calgary6. In just 22 days, more than 60 additional examination spaces were added next to the ED, in a separate prefabricated space donated by Sprung Structures and using modular Falkbuilt headwalls. Clinicians refer to it as “a godsend” and plan to continue using it beyond Covid as an ED overflow space for many other types of patients.

Why wouldn’t we explore similar solutions for the mental health pandemic?

If 20 years ago, a large urban hospital ED had one or two exam rooms designated for mental health patients, our large ED designs today include full-size dedicated pods of ten to 12 exam rooms. This is hardly a sustainable trend, given the loud and chaotic nature of the ED and its general unsuitability for mental health patients (e.g. lack of therapeutic milieu, general lack of natural light, or even lack of mental health providers). Studies show that it may indeed exacerbate underlying conditions, such as anxiety, frustration, and agitation, further traumatising these patients.

Much as has been the case during the Covid-19 pandemic, successful solutions for a highly resilient healthcare system include those focused on keeping these patients away from the hospital emergency departments altogether.

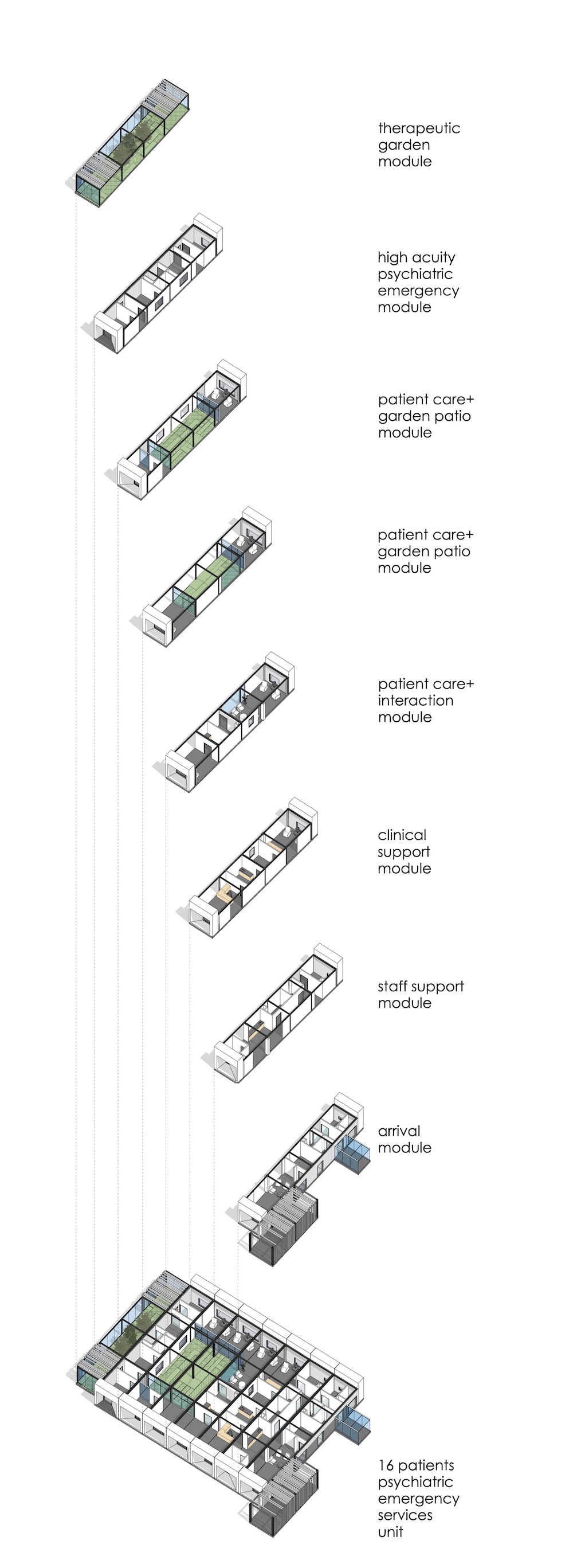

Consider this: modular prefabricated crisis units, designed to fit in the width of a standard parking aisle, independently accessed and, if desired, with the option of sharing a back-of-house connection with the hospital. Small hospitals in California typically benefit from a crisis unit sized for between four and eight patients, while a highly efficient unit can accommodate 16 patients and would be better suited to medium-sized to large hospitals. Designed as OSHPD 3 structures (the California Building Code designation for ambulatory healthcare settings) for a length of stay of up to 23 hours, these crisis units should include one or more therapeutic garden modules – an indispensable and intrinsic part of the therapeutic environment.

Important benefits for the hospital

For every patient who can be transferred out of the ED into a dedicated modular crisis unit, up to three other patients could be seen and treated in that same ED.

For many hospitals, this solution also presents an additional revenue opportunity via increased ED throughput, given that the average cost to an ED to board a psychiatric patient is estimated at $US22647,10.

Benefits compound at the community scale if we consider that for every patient in crisis, either the police or the paramedics must spend the same average ten hours waiting with the patient in the ED or that the hourly cost of ambulance diversion is estimated around $US5400 (State of California practices involuntary holds put on patients considered a potential threat to either themselves or others, aka US Code 5150). Once freed, that time could be spent instead on saving lives in our communities.

What’s more, rapid regional deployment in a hub-and-spoke model can serve to address rural healthcare disparities.

A great example of one such programme is Alameda County’s John George Psychiatric (JGPH) Emergency Services facility, which works in conjunction with 11 EDs in the region, receiving medically stable mental patients in need of mental health assessments and referrals to either inpatient or outpatient care. The Alameda model focuses on immediate treatment in an outpatient setting, with the goal of avoiding hospitalisation. It bypasses medical emergency rooms completely in two-thirds of cases, further reducing issues of regional overcrowding.

The facility houses 80 patients in a combination of beds and sleeper chairs, plus three seclusion rooms, and provides psychiatric evaluation, intervention, and referral for voluntary and involuntary patients 24/7, 365 days/yr. One can go to John George for walk-in, in-person support in case of an immediate crisis. Crisis intervention and urgent medication assessments are provided by qualified, multidisciplinary teams of mental health professionals. The treatment and management of psychiatric care at JGPH is nationally recognised as a best practice and is a model for many other programmes across the country8.

The results speak for themselves when a regional model is applied, with a documented 80-per-cent reduction in ED boarding time, from an average of ten hours to 1 hour and 48 minutes for psychiatric patients, with 75 per cent of these patients being discharged to continued care in the community9.

Dr Scott Zeller pioneered the emPATH Unit approach (emergency medicine Psychiatric Assessment, Treatment, and Healing10 while working as chief of psychiatric emergency services at JGPH:

“It averages 1200-1500 very high-acuity psychiatric patients per month, approximately 90 per cent in involuntary detention, and focuses on collaborative, non-coercive care, involving therapeutic alliance when possible. Presently, it is averaging 0.5 per cent of patients placed in seclusions and restraints – comparable US psychiatric emergency services programmes average 8-24 per cent of patients in seclusions and restraints.

“Typically, regional approaches make sense for systems with volumes higher than 3000 psychiatric emergencies per year. It is a model of great interest for insurance companies, which are often willing to pay more than the daily rate for inpatient hospitalisation7.”

The return of investment for healthcare systems adopting the regional model can indeed be significant, as has been shown in the US case studies published by Vituity11.

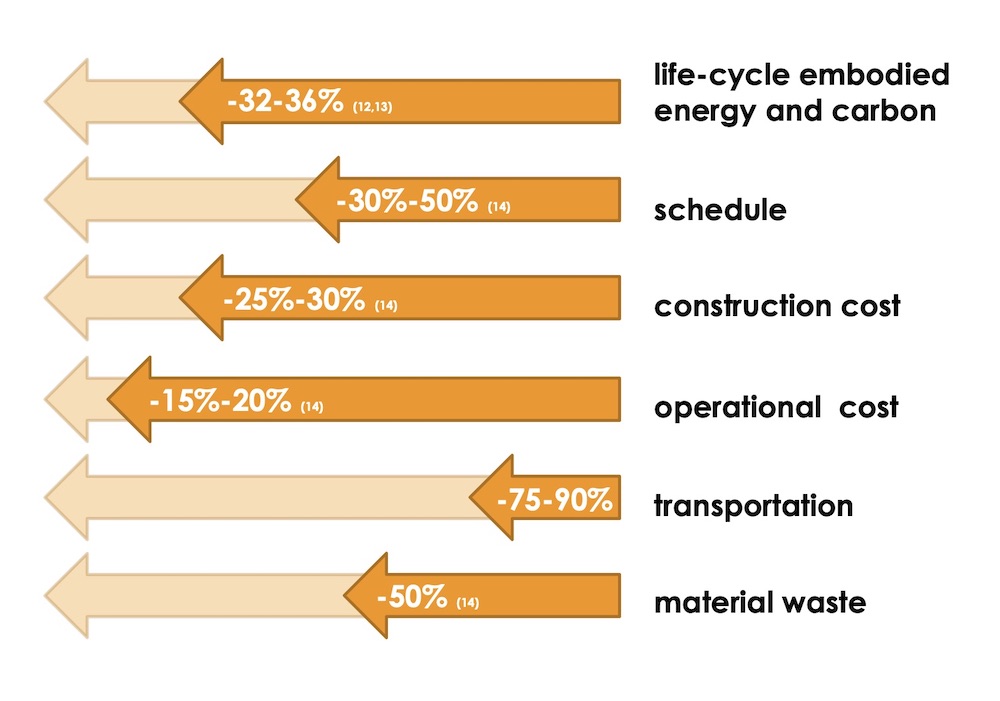

Designed for incremental, organic growth as the needs of the organisation evolve, the modular prefabricated units retain and recover as much value as possible from resources by reusing, repairing, refurbishing, remanufacturing, repurposing, or recycling products and materials. When compared with traditional construction, a modular prefabricated solution can deliver significant benefits, beyond the often-mentioned schedule and cost12,13,14.

There are other significant benefit, too:

- Better quality control and a reduction of energy use during construction as factories are better equipped to control emissions when compared with traditional construction sites. With a shorter construction period and fewer on-site workers, energy use is much reduced.

- Plug-and-play assembling methods allow for increased potential to adapt, reuse, and recycle the modules, as they can be easily disassembled and modified.

- Steel structure modular buildings can be as wind-resistant or earthquake-resistant as traditional structures, and therefore just as resilient.

- Better indoor air quality can be achieved given that factory-based construction methods allow for a larger period of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) off-gassing from sealants and adhesives, while moisture control can be more easily achieved in a controlled factory environment.

- In general, modular projects will be much less disruptive to the community environment through noise and pollution levels, given their reduced site construction period and reduced requirements for site traffic and site material storage.

Beyond strengthening a system’s resiliency and ability to meet mental health needs, the biggest positive impact will be on the patient experience. These modular units, unlike an ED, are designed to provide a supportive and calm environment with abundant access to sunlight and nature, attributes that can make all the difference to someone experiencing a mental health crisis. To be most effective, staffing models need to consider a combination of peer and professional support.

Crisis stabilisation units need to be staffed round the clock, all year round, with a multidisciplinary team capable of meeting the needs of individuals experiencing all levels of crisis in the community. The team should comprise: psychiatrists or psychiatric nurse practitioners (telehealth being an option); nurses; licensed and/or credentialed clinicians capable of completing assessments in the region; and, importantly, peers with lived experience similar to the experience of the population served15. Connecting with people who have been there themselves and can help guide one out of a crisis is an essential part of the experience.

We see the therapeutic garden and green patio as critical indispensable programmatic elements, with several recent studies having clearly demonstrated how proximity to greenery and immersion in nature lowers levels of anxiety and stress16. When coupled with open, accessible layouts that offer patients a variety of options regarding levels of stimulation and engagement, natural elements will offer a radically different feel to the space when compared with not just the average emergency departments but the majority of hospital environments.

In most of our healthcare systems, the continuum of care for patients with mental health issues has numerous gaps. This solution addresses one of the most difficult pressure points and can do so much faster than any traditional construction approaches. It will allow our healthcare systems the necessary time to prepare profound medium- and long-term solutions. These will need to involve training and re-training of primary healthcare providers, as well as adjusting the ways we build our hospitals and community care centres around our patients, while recognising that these days, mental health issues are just as prevalent as arthritis.

As designers, by joining forces with our construction industry partners, we can take a bite out of the mental health pandemic, too.

About the author

Maria Ionescu BArch OAR OAA NCARB is a senior healthcare architects and senior associate at Stantec, in Los Angeles.

References

- Leeb, RT, Bitsko, RH, Radhakrishnan, L, Martinez, P, Njai, R, and Holland, KM. (2020). Mental health–related emergency department visits among children aged <18 years during the Covid-19 pandemic – United States, January 1–October 17, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep (MMWR); 2020. [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6945a3.htm

- Jones, SE, Ethier, KA, Hertz, M, et al. (2022). Mental health, suicidality, and connectedness among high school students during the Covid-19 pandemic – adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Suppl.; 2022. [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/su/su7103a3.htm

- The US Mental Health Market, an OPEN MINDS Market Intelligence Report. (2020). [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/2019-us-mental-health-spending-topped-225-billion-with-per-capita-spending-ranging-from-37-in-florida-to-375-in-maine--open-minds-releases-new-analysis-301058381.html

- Expenditure on mental health services. (2020). Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/030bb981-9de2-4520-8831-d9ddff1f6c4a/Expenditure-on-mental-health-related-services-2019-20.pdf.aspx

- Allison, S, Bastianpillai, T, O’Reilly, R, Scharsfstein, S, and Castle, D. (2018). Widespread emergency department access block: A human rights issue in Australia? [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1039856218810156?icid=int.sj-abstract.similar-articles.2

- Gervais, B. (2022). Calgary pandemic response unit should relieve some hospital strain, doctors say. [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://calgaryherald.com/news/local-news/calgary-pandemic-response-unit-should-relieve-some-hospital-strain-doctors-say

- Nicks, B, and Manthey, D. (2012). The impact of psychiatric patient boarding in emergency departments. Emergency Medicine Int. [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22888437/

- Alameda Health System website. (2022). [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: http://www.alamedahealthsystem.org/locations/john-george-psychiatric-hospital/

- Zeller, S, Calma, N, and Stone, A. (2013). Effects of a dedicated regional PES on boarding of psychiatric patients in area emergency departments. [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/01s9h6wp

- Zeller, S. (2017). emPATH Units as a solution for ED psychiatric patient boarding. [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://www.psychiatryadvisor.com/home/practice-management/empath-units-as-a-solution-for-ed-psychiatric-patient-boarding/

- Emergency psychiatric intervention (EPI): Integrated ED patient care. (2022). Vituity. [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://www.vituity.com/redefining-ed-behavioral-healthcare/?utm_source=Beckers&utm_medium=BD_OAD&utm_campaign=BD_2021_Q3_OAD:Beckers_eNewsletter_EPI_0809&utm_content=EPI

- Azzouz, A, Borchers, M, Moreira, J, and Mavrogianni, A. (2017). Life cycle assessment of energy conservation measures during early stage building design: A comparative study in London, UK. Energy and Buildings. vol. 139, pp 547-568. [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378778816320813

- Jang H, Ahn Y, Roh S. (2022). Comparison of embodied carbon emissions and direct construction costs for modular and conventional residential buildings in South Korea. Buildings. 12(1), 51. [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12010051 and https://www.mdpi.com/20755309/12/1/51

- McGraw Hill Construction Study. (2011). Prefabrication and modularization: Increasing productivity in the construction industry. [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/el/economics/Prefabrication-Modularization-in-the-Construction-Industry-SMR-2011R.pdf

- National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care. (2020). SAMSHA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/national-guidelines-for-behavioral-health-crisis-care-02242020.pdf

- Thompson R. (2019). The use of gardening and green space therapy in mental health is increasingly important. Journal of Mental Health and Clinical Psychology; 2019. [Internet] [cited May 2022]. Available from: https://www.mentalhealthjournal.org/articles/the-use-of-gardening-and-green-space-therapy-in-mental-health-is-increasingly-important.pdf

Organisations involved